By Allison Fedirka and Xander Snyder

There were several developments this week in China and the Philippines that appear unrelated on the surface but actually interact and affect the balance of power in East Asia. The first item relates to international concern with China’s debt, which Geopolitical Futures has been tracking for some time. The second development concerns a series of events in the Philippines. They illustrate the country’s instability and the difficulty confronting China in its attempts to pull the Philippines closer and away from its traditional ally, the United States.

Concerns About Chinese Debt

On May 24, credit ratings agency Moody’s downgraded China’s government debt by one level, from Aa3 to A1. Much of the rationale for the agency’s decision parallels what Geopolitical Futures outlined in our 2017 forecast for China. At the end of 2016, we anticipated that China would confront the political and economic fallout from slower growth rates in the country. On the one hand, Beijing needs to implement tough reforms for the long-term health of its economy. But on the other hand, China is a massive country whose central government has leaned on short-term growth to maintain social stability among its population of around 1.3 billion people. Switching its focus from immediate to long-term objectives is necessary but requires a deft hand.

The Moody’s report is evidence that the problems in China’s economy are beginning to be recognized as a geopolitical reality with implications not only for China but also for the balance of power in East Asia. What the ratings agency’s report misses, however, are the structural political-economic factors driving debt growth in China and the implications that important reforms will have on the country. Debt and slower growth are not the causes of China’s problems; they’re symptoms of deeper issues. The missing link here is an understanding of how China’s debt issue is, ultimately, also a political issue.

The Chinese economy has become overreliant on real estate. The lack of appealing alternative investment opportunities combined with restrictions on capital outflows have driven excess capital into real estate, significantly increasing prices in markets across the country. More companies have moved into real estate, including construction, which has created many jobs. To avoid a sudden spike in unemployment in urban areas – which would be a recipe for unrest that could challenge the government’s core – the Communist Party has had to support inefficient companies with debt. Reducing this support through reforms would be necessary to decrease debt growth, but that is politically untenable.

One direct solution would be to let real estate prices fall, which would risk bankrupting developers. The harder approach, but one less likely to lead to social unrest, would be to reallocate capital more efficiently – in other words, rely less on the real estate sector. But China’s lack of a strong domestic consumption base means that even if new enterprises were to receive more capital, they would have a difficult time finding domestic customers to sell to. (The other option would be to turn to exports, but China will run into problems there too.) Creating a diversified consumer economy isn’t something that happens in just a few years.

It goes without saying that the health of the world’s second-largest economy – East Asia’s largest economy – has global implications. The tension between reform and stability dictates the limits of China’s influence in East Asia and ability to build strategic relationships with its neighbors. Beijing has adopted the soft-power tool of money (project funding, investments, business) to expand its reach. It may not be the most novel approach, but it can be effective. But a major economic crisis at home means less money for investments and thus less influence.

Of particular import is how economic problems could hold back China’s relationship with the Philippines. The island nation matters a great deal to China because it sits in the way of China’s direct access to major trade routes in the Pacific Ocean via the South China Sea.

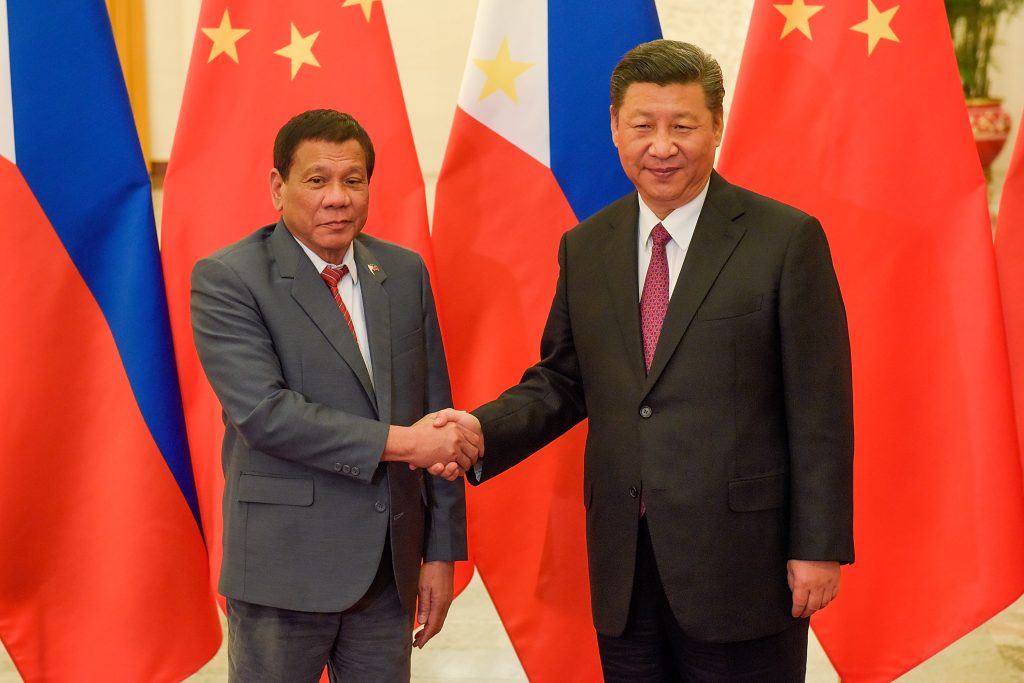

Beijing has directed its soft power at the Philippines: Last October, at their first bilateral meeting as heads of state, Chinese President Xi Jinping promised Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte $24 billion worth of Chinese investments. The financial approach has improved bilateral ties between Beijing and Manila, but it hasn’t completely won over the Philippines. It’s actually been the United States that since World War II has been the Philippines’ main partner. Washington, like Beijing, is aware of the problems the Philippines could create for Chinese maritime trade if it wanted to. Rather than pick one country to partner with, it makes the most sense for Manila to retain some independence and play larger powers off one another to get the most concessions possible from each.

The Philippines’ Strategy

This week three events took place that illustrate the Philippines’ strategy. First, Duterte traveled to Russia to meet with President Vladimir Putin. The meeting itself isn’t very important, especially since, right now, Russia has little to offer the Philippines that could compete with what China or the U.S. offers. By reaching out, however, Duterte can show Washington and Beijing that Manila is willing to look elsewhere to get what it wants (in this case, military-grade weapons).

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) shakes hands with Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte prior to their bilateral meeting during the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation at the Great Hall of the People on May 15, 2017, in Beijing, China. Etienne Oliveau/Pool/Getty Images

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) shakes hands with Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte prior to their bilateral meeting during the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation at the Great Hall of the People on May 15, 2017, in Beijing, China. Etienne Oliveau/Pool/Getty Images

The second event was the leak of the transcript of the April 29 phone call between Duterte and U.S. President Donald Trump. During the conversation, Duterte expressed his support for the U.S. position in the Korean Peninsula and encouraged Washington to keep up the pressure on North Korea. He then remarked on the importance of China’s role in reining in North Korea. By the end of the call, Duterte had positioned himself as a go-between for the leaders, agreeing to speak with Xi on Trump’s request about North Korea.

It’s a mystery why the transcript was leaked – and why now – but we can offer some likely scenarios. Given the conversation’s focus on China’s relationship with North Korea, the leak could be meant to pressure Beijing to follow through on its agreement to calm down the situation. Another possibility is that the release is intended to portray Duterte as a strong leader who has direct and balanced ties to both Xi and Trump. In this sense, it would have been meant to reassure other members of the government as well as his critics that Duterte is not favoring either side or selling the country out. On a related note, at one point during the call, Trump compliments Duterte’s accomplishments in fighting drug traffickers at home. This could be interpreted as meaning the U.S. no longer takes great issue with potential human rights abuses arising from Manila’s drug enforcement measures and lays the groundwork for healing this component of the bilateral relationship with the United States. Whatever the reason for the leak, there’s a good chance it was part of the Philippines’ strategy of political maneuvering to increase the country’s standing with China and the United States.

Finally, there was Duterte’s decision to declare a state of emergency on the island of Mindanao after Muslim extremists tried to take over Marawi, a town with about 200,000 inhabitants. In a coordinated attack, an estimated 100 militants beheaded the local police chief, took at least a dozen hostages in a church, burned down public buildings and raised the Islamic State flag over town hall. Low-level Muslim extremism has been a problem for the Philippines for years, but this most recent incident marks an escalation in intensity and sophistication. Between this escalation and the fact that Duterte regularly links his administration with increasing safety and public order in the Philippines, a strong government response was needed.

The incident also creates a new space for international partners to vie for cooperation. The U.S. helped combat extremism in the Philippines in the past with Operation Enduring Freedom, which ended in February 2015, so an IS-linked attack could pave the way for renewed anti-terrorism cooperation with the United States. The IS link also shows how easily the jihadist ideology can spread to other regions and organize forces already in the country. This is particularly concerning for China, which fears similar behavior from its Uighur minority population. In this sense, China, too, has reason to offer counterterrorism cooperation with the Philippines.

The balance of power in East Asia exists in a dynamic geopolitical environment. The Philippines’ strategy to play its potential partners – namely the U.S. and China – off one another means the situation is regularly in flux. China’s ability to play the game is directly related to its ability to use financing to win the Philippines over. The effects of continued slower growth and growing debt in China can eventually wear away Beijing’s ability to court the Philippines at a time when the United States will be doing the same.