By Jacob L. Shapiro

On July 27, the AFP news agency reported that U.S.-backed Syrian rebel groups in southern Syria were opening up a “new front” in the war against the Islamic State. The story was not widely picked up at the time, but it has recently set off alarm bells in Jordan, which shares a large part of its northern border with Syria. The headline – “Coalition Aims to Open New Anti-IS Front in Syria: US” – is somewhat misleading, but there have been some important developments in southern Syria, which has taken a back seat as much of the world’s attention is focused on the battle for Aleppo raging in the north.

On Aug. 8 and 9, a slew of reports appeared in the Jordanian press, quoting former military officers and various commentators who all said that Jordan should absolutely not be dragged into new military operations in support of the United States in southern Syria. These reports also contained concerns that the new offensive AFP reported might cause large numbers of refugees to head for Jordanian territory, or even encourage attacks on Jordanian targets by either the Islamic State or jihadist anti-Assad rebel groups active in the area.

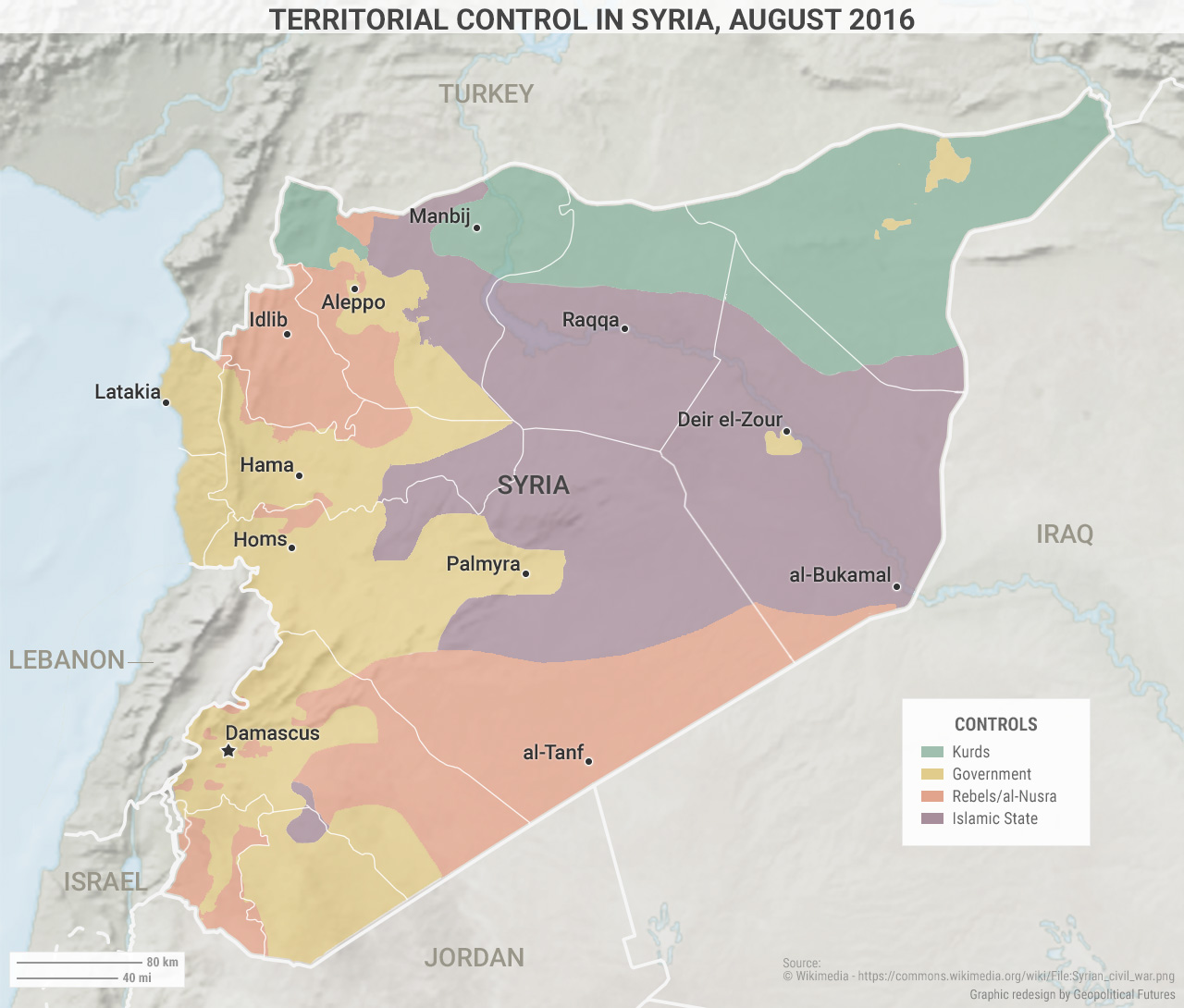

The first thing to note is that there is no new offensive front being opened up, currently or imminently, in southern Syria – not in the region of Daraa, nor further east where the borders of Syria, Iraq and Jordan converge. This border is roughly 81 miles south of one of IS’ most strategically important positions in the city of Deir el-Zour. The AFP report and the subsequent concern have been based on one piece of evidence: a speech made by U.S. Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter to the 18th Airborne Corps at Fort Bragg. Carter, however, said nothing about a new front. He merely said that the U.S. would continue to “aggressively pursue opportunities to build pressure on IS in Syria from the south.” Neither Carter nor the U.S. has said anything else on the matter. There’s a lot of daylight between what Carter said and the assertion that a new front is being opened up.

However, this story is still important because it indicates that Jordan is nervous about what is happening in southern Syria.

Jordan is worried about two things in particular. First, it does not want to become a more attractive target for the various militant groups – whether they be the Islamic State or jihadist groups more focused on getting rid of Bashar al-Assad – that are operating to Jordan’s north. That means Jordan wants to stay out of the fray as much as possible. Second, Jordan wants to avoid taking in more refugees than it has to. European nations like to complain about how they have a migrant crisis on their hands. Jordan, according to the U.N. refugee agency, has received over 650,000 Syrian refugees since 2011 – and those are only the registered ones. Syrian nationals now make up over 20 percent of Jordan’s total population. That is a real migrant crisis, and it is a minor miracle that the stresses from migration haven’t already overwhelmed the Jordanian system.

The problem for Jordan is that Syria’s southern front has been unstable in recent months. The first problem is the Islamic State. IS has given up some (less important) strategic positions in Iraq and central Syria in recent months, but in southern Syria it has scored some quiet victories. At the end of June, a few hundred fighters from the U.S.-backed and trained New Syrian Army (NSA) attempted to dislodge Islamic State from al-Bukamal – a strategically important city for IS. After the NSA achieved some success, IS repelled the NSA attack handily.

IS has continued to press the fight on this axis. On Aug. 7, it attacked a base near the al-Tanf border crossing between Syria and Jordan. The IS attack was not successful, but just the fact that it repelled the NSA and then was able to follow up with a separate attack on a base roughly 124 miles from al-Bukamal is an example of IS’ strong fighting capability. IS has also been slowly advancing on Palmyra, which it retreated from in March and where 1,000 fighters from pro-Iranian militias were recently deployed to shore up the city’s defenses. The narrative around IS is that it is weakening and that its doom is at hand. IS is certainly under pressure, but this is an important reminder that it remains capable of defending strategically important points and being aggressive when it wants to be.

The second issue is the status of the relationship between Russia and the United States in this theater. For a while, there had been, if not an alliance, an understanding between U.S.-backed rebel groups and the ex-al-Qaida affiliate, formerly known as Jabhat al-Nusra, in the southwest, particularly in Daraa province. However, the group, now called Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, pulled its fighters out of the battle against IS-affiliates in the southwest at the end of July, which is concerning for Amman because Jordan has quietly encouraged al-Qaida ideologues as a counter to IS. Reports on why the former al-Nusra pulled back are sketchy at best, but there are two likely possibilities. The first is that it needs the fighters to strike at the Assad regime, especially with Aleppo’s fate currently in the balance further to the north. The second relates to the deal reached by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov on July 15. The U.S. and Russia agreed to work together in Syria to target both the Islamic State and the former al-Nusra. The logic here would be that the group pulled back because it was vulnerable to a potential combined U.S.-Russian offensive in southern Syria.

The problem is that the status of U.S.-Russian cooperation on Syria is uncertain and has been for years. In June, for instance, U.S.-backed NSA fighters near al-Tanf were reportedly bombed by Russian planes. The Russian Defense Ministry claimed a week later that it had done nothing wrong – that the target it bombed was over 186 miles from any area in which the U.S. told Russia U.S.-backed fighters were active. Despite this incident, the U.S. has continued to court Russia. Kerry said on July 26 that he hoped to announce in early August that Russia and the U.S. will agree to greater levels of military cooperation and intelligence sharing in Syria. It may be that the announcement is still to come, but either way, with a budding Turkish-Russian rapprochement and ominous signs emanating from Ukraine, the tensions between Russia and the U.S. are only increasing in the short term, and that increases uncertainty in Syria.

Aggressive IS movements, shifting alliances between rebel groups and an unclear relationship between Russian and U.S. forces together explain why Jordan is getting anxious. And this is important because Jordan has proved to be one of the few allies the United States and others fighting the Islamic State have in the region. Jordan is already under tremendous strain, and its nervousness likely means it sees developments unfolding in a way that poses a potential threat. Therefore, it behooves us to try and see what Jordan sees beyond the headlines.