By Phillip Orchard

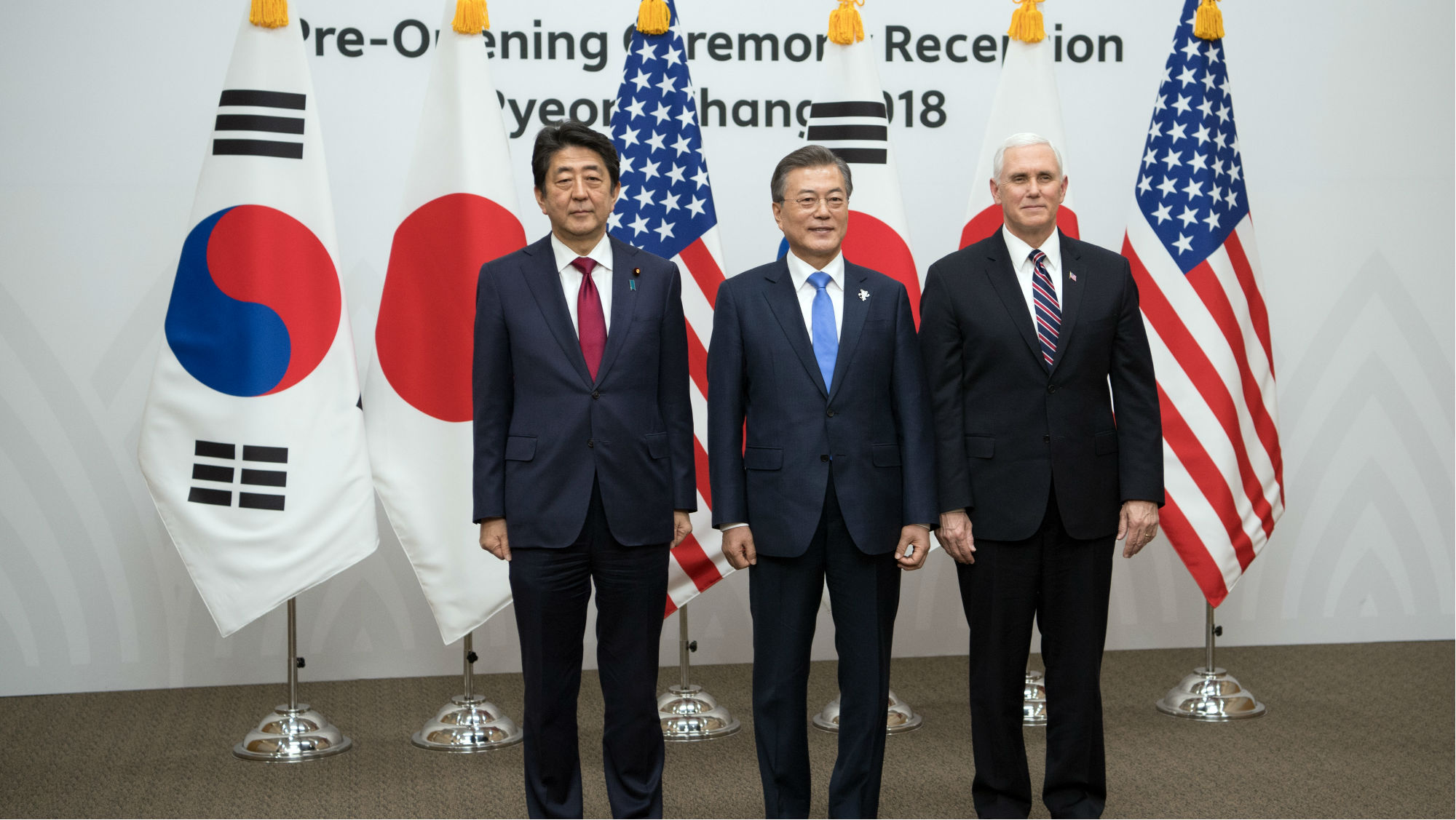

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe isn’t having the best Olympics. Over the weekend, at a meeting with South Korean President Moon Jae-in ahead of the opening ceremonies, Abe’s goal was to secure a commitment that Seoul would resume joint military drills with the U.S. after the Paralympics end in March and to sustain sanctions pressure on Pyongyang, while refraining from spiking a 2015 accord intended to resolve lingering animosity over Japanese abuses in World War II. According to South Korean media, Moon told Abe not to meddle in the South’s “sovereignty and internal affairs,” and essentially sent Abe to his room to think about Japan’s past bad behavior.

Abe also had to watch as the nascent detente between the two Koreas picked up pace, culminating with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un inviting Moon to an inter-Korean summit in Pyongyang. During his meeting with the North Korean delegation headed by Kim’s sister, Moon reportedly declined to press Pyongyang to denuclearize, heightening concerns among the U.S., Japan and hawks in South Korea that Moon’s government may be laying the groundwork to weaken sanctions pressure on the North and potentially extend the temporary freeze in U.S.-South Korea joint exercises. Adding apparent insult to injury was yet another show of support from the Chinese for South Korea’s pursuit of reconciliation with the North, stoking concern that Beijing is succeeding in using the Korean crisis to drive a wedge between Seoul and its stalwart allies.

All of this highlights an uncomfortable reality for Japan: It is perhaps the country most vulnerable to a nuclear North Korea – including even South Korea – but also, of all the key players involved in the standoff, the one with the least ability to independently shape the outcome of the crisis. It’s a peripheral player and likely will be until the crisis is settled one way or another. But it’s also on a path to ensure that it doesn’t find itself confined to the sidelines in this sort of situation again.

Seoul Keeps Its Enemies Closer

The weakness of Japan’s hand is reflected in the peculiar dynamic that has emerged between South Korea and the two rivals on its flanks.

Seoul’s apparent embrace of Beijing while giving the cold shoulder to Tokyo may seem mystifying. After all, it was China that implemented informal economic sanctions on South Korea last year over Seoul’s decision to go forward with the U.S. deployment of the THAAD ballistic missile defense system – a strategically dubious (and ultimately futile) attempt to coerce Seoul into prioritizing Chinese security over its own in the middle of a crisis. During a high-profile visit to Beijing last fall, when the two sides made a show of unity by jointly declaring that war could not be allowed on the peninsula, Beijing signaled that it would continue to inflict economic pain on the South whenever it strayed from Chinese wishes – despite Seoul agreeing to refrain from additional THAAD deployments. And it’s China that is helping keep the North Korean regime afloat more than any country, except possibly Russia, by blocking U.S.-led attempts to strengthen U.N. sanctions on Pyongyang, particularly with regard to oil imports.

Yet South Korea has reportedly remained reluctant to implement parts of a landmark intelligence-sharing pact with Japan brokered by the U.S. in 2016. Some of this has to do with Seoul’s lingering resentment over Japan’s prewar occupation of Korea and unease about Japan’s growing determination to shed its postwar pacifist constraints. Some of it has to do with the perception that Japan is acting merely as a U.S. proxy to pave the way for a U.S. military operation on the peninsula over Seoul’s objections – a move that would put the South Korean capital region at risk of massive North Korean shelling. But mostly it has to do with the fact that China simply matters more than Japan in the current crisis.

That said, Chinese influence in Pyongyang has waned considerably since Kim Jong Un came to power. Though China has thrown its rhetorical support behind Moon’s detente with Pyongyang, it’s unclear what Beijing could really do to push talks toward a resolution that both it and Seoul would find acceptable. China’s overriding goals are to expel the U.S. from the peninsula and to ensure that a friendly, or at least not overtly hostile, government rules the North. These, along with the long-term threat China poses to South Korea, limit how far Seoul can align itself with Beijing in the current crisis – especially if Seoul succeeds in persuading the U.S. to refrain from a unilateral operation to disarm the North.

Nonetheless, Beijing still has as much leverage over North Korea as anyone. Even if it cannot bring Pyongyang fully to heel without harming its own core interests on the peninsula, it at least has some latent ability to alter Pyongyang’s cost calculations and, if enough stars align, potentially help the North Koreans save enough face to be willing to stand down. At minimum, China doesn’t want to see a war on the peninsula that puts U.S. forces on the Yalu River and a pro-U.S. government in Pyongyang, which means Beijing certainly isn’t going to try to thwart Seoul’s efforts to forestall a conflict through dialogue. This makes Seoul’s alignment with Beijing at this stage low risk. As was made clear when Vice President Mike Pence said that the U.S. was open to talks with the North without preconditions, at this point, “maximum pressure” and dialogue need not be seen as automatically conflicting.

Japan, in comparison, just doesn’t have the ability to either substantially further or frustrate Seoul’s objectives. Of all the relevant players, it has the least leverage over Pyongyang. It cannot yet act on its own militarily to eliminate the threat, as its slow remilitarization is still in its very early stages. Even new landmark procurements that would give it at least limited ability to strike the North, such as long-range cruise missiles, are expected to take years to complete. The best it can do for the foreseeable future is align itself with the U.S.

Thus, to South Korea, Japan may either lend a helping hand or become a threat, but at the moment there’s little downside to pushing Tokyo on politically explosive but strategically unimportant issues such as wartime “comfort women” and tiny islands in the Sea of Japan. In fact, it’s convenient to do so at a time when Moon is facing heavy criticism from South Korean conservatives and widespread public skepticism about his hearty welcome of the North Koreans at the Olympics.

Japan’s Long Game

To be clear, Japan can be a pivotal player in support of how the U.S. and South Korea decide to proceed. The Americans would lean heavily on Japanese help to facilitate and contain the fallout of a U.S. military operation. Short of war, Japan could play a valuable role in implementing a blockade on the North. It’s already using its diplomatic and economic influence across Asia and beyond to quash North Korea’s efforts to circumvent sanctions. If and when everyone simply decides to live with a nuclear North, Japan’s superb intelligence, submarine warfare, anti-ballistic missile systems and anti-mining capabilities would be invaluable in deterring Northern aggression.

But no country with Japan’s combination of untapped power and inherent vulnerabilities would be content with the role of good team player executing someone else’s strategy indefinitely. Tokyo is certainly not sitting on its hands. Japan may not have many options today, but it’s moving to ensure that it doesn’t find itself in this sort of situation in the future.

This is why Japan has been spearheading efforts to lay the groundwork for a tightened defense framework anchored by Australia and India, while also gradually ramping up security and economic assistance to strategically important ASEAN states locked in territorial disputes with China. Alongside this effort, Japan has also been the driving force behind the revival of the strategic Trans-Pacific Partnership, that, despite appearing dead following the U.S. withdrawal early last year, appears set to be finalized by the remaining 11 members later this year. Finally, at home, Japan is moving methodically to shed legal and political constraints on remilitarization, while slowly building up military capabilities that will give it greater ability to step out from under the U.S. security umbrella and secure its vital interests farther afield.

None of these efforts appears ready to come to fruition quickly, whether due to conflicting interests among the regional states Japan is trying to shepherd toward tighter cooperation, or due to powerful and unpredictable political currents at home. Nevertheless, the disquieting realities exposed by the Korean impasse – the limits of U.S. power in the Indo-Pacific, uncertainties about whether South Korea will remain a part of the U.S.-led alliance structure, and Chinese disinterest in working to preserve the established order – have certainly helped them gain traction. In this way, being confined to the sidelines in today’s crisis may ultimately help Japan get where deeper geopolitical forces are urging it to go.