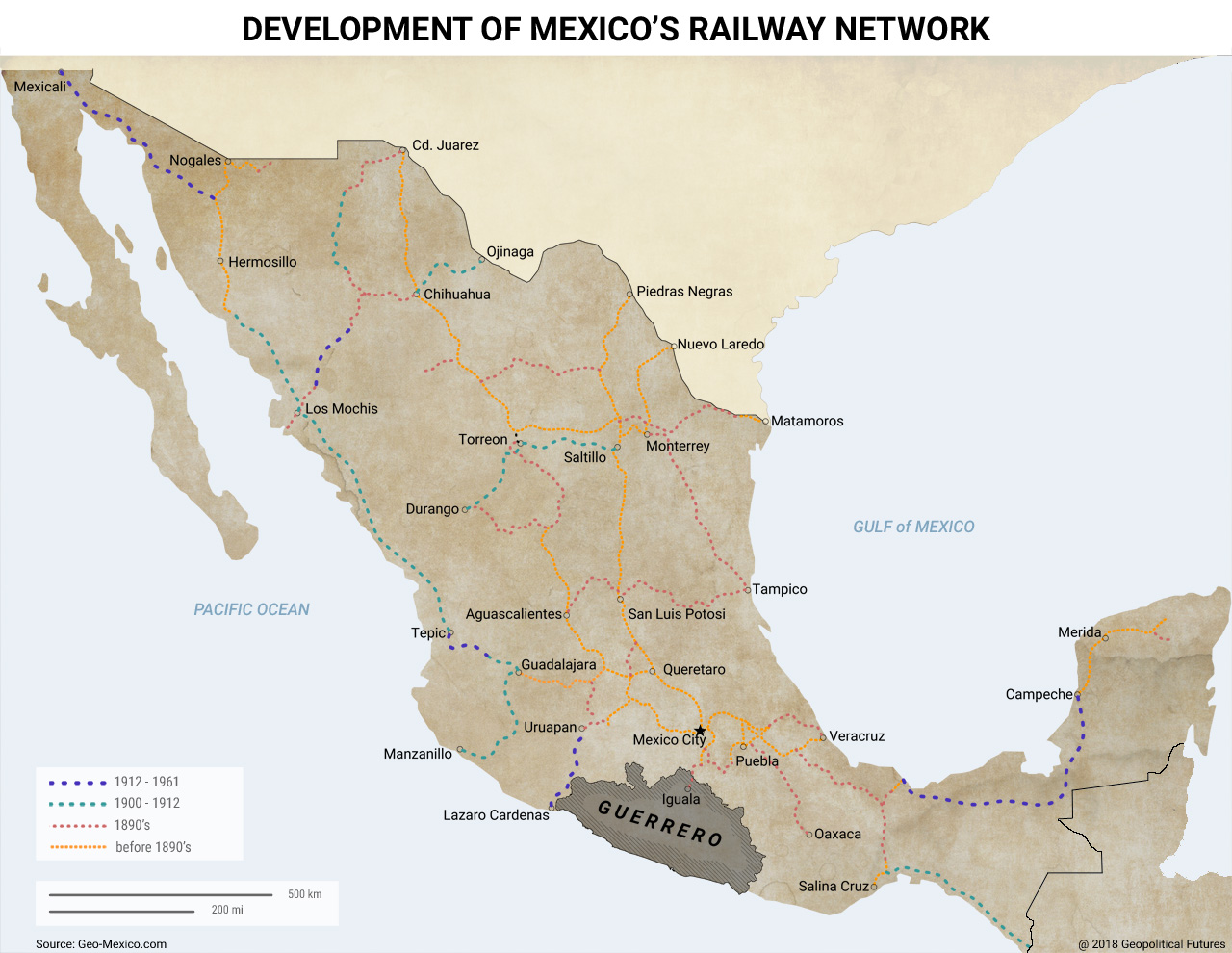

This can be seen through the lack of infrastructure in the state. Mexico experienced a wave of infrastructure development after the second French intervention in the 1870s and during the early years of the Diaz government in the 1880s. In 1860, Mexico had but 150 miles of disjointed railway. Just 24 years later, this grew to 7,500 miles. Initially, officials wanted to construct a rail line linking Veracruz on the east coast with Acapulco, a port city in Guerrero, via Mexico City. But ultimately, they did not follow through, and Guerrero was largely left out of the infrastructure boom, a fact that has limited the state’s development ever since.

The state was left out because its mountainous terrain makes infrastructure development costly. Heavy rain during summer months also makes construction harder and increases the cost of maintenance for existing tracks. At the start of the railway boom, private companies and investors from the U.S., U.K. and elsewhere funded infrastructure projects and choose which projects to invest in based on their own business interests. In Guerrero, business interests mainly related to mining. The northern part of the state is rich in minerals and metal deposits. There was thus enough financial incentive to construct a railway from Mexico City to Iguala, located in the mining region and relatively close to Mexico’s capital.

But when metal prices fell at the end of the 19th century, investor interest in the state waned. It was around this time, in 1898, that the federal government stepped in to regulate railway construction and, in so doing, put the final nail in the coffin for Guerrero’s development. The federal government intervened for two reasons. First, it needed to fill the gap left by the private sector. The fall in metal prices hit Guerrero particularly hard, but it affected the mining industry, and therefore infrastructure development, across the country. This would have almost immediate impacts on local populations and economies that the Diaz government had been so dedicated to supporting in the previous decade.

Second, the government wanted a national approach to infrastructure development to ensure that the decisions being made on which projects to support and which areas received the most investment were in the best interests of the country. This resulted in legislation that limited foreign participation in infrastructure, gave the government more control and introduced a period in which projects needed government subsidies before they could move forward. But the central government did not consider Guerrero a priority for rail construction, and therefore the extension of the railway to Acapulco was abandoned.