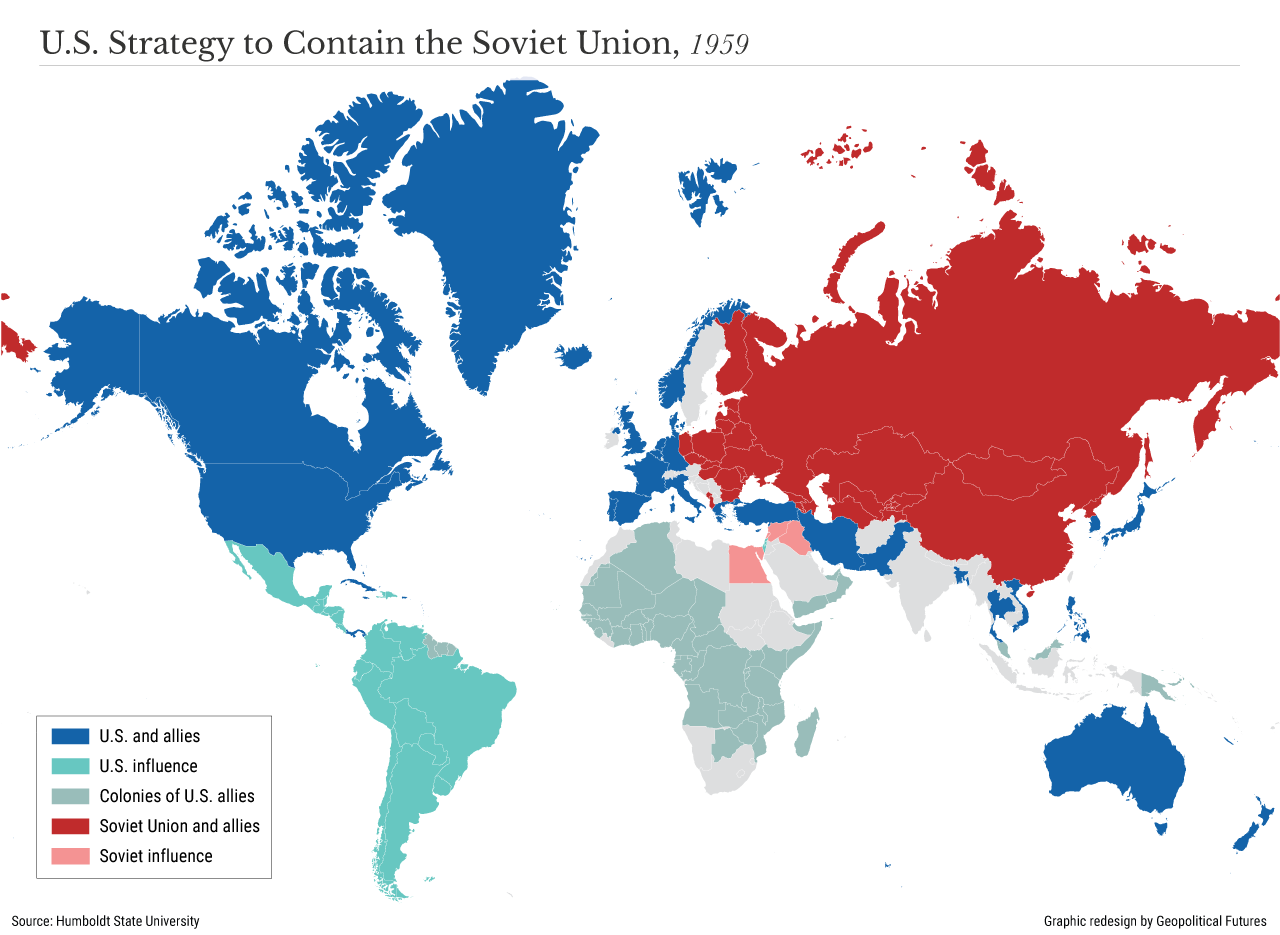

During the Cold War, the United States opposed the Soviet Union wherever the Soviet Union sought to make inroads. Some interventions were necessary and therefore took place in obvious locales: in Germany to shield Europe, in Turkey to limit Soviet naval movement into the Mediterranean, and in Japan to block the Soviet port of Vladivostok and the Pacific. Others such as Angola and Afghanistan were less so.

The United States was in a global competition with the Soviets, and they both used the tools they had available to counter each other. Washington’s primary tool was its military, particularly its massive navy. Moscow’s was what were called “wars of national liberation.” They involved covert support to insurgents in countries throughout the world, most notably in former colonies of European imperialists. The United States usually had little interest in the battleground country. It had an overriding interest in blocking Soviet success in these countries, since success might create the perception of greater Soviet power. The U.S. tended to use covert forces to wage a covert war against Soviet proxies, though some such as Vietnam are notable exceptions.

During the Cold War, everything mattered to the United States, because the Soviets could and would exploit any opening. The Soviet Union was a global power, with a military second only to the United States’ and a covert capability that frequently put Washington in difficult situations.

But there is no threat from the Soviet Union today. Only some things now matter to Washington. This is a shock to a world that expects the U.S. to take a leadership role, indifferent to the price the U.S. paid in the Cold War for taking the reins. Engaging globally carries with it a high price that can be paid when necessary but should be avoided when possible.

Between then and now, in late 2008, Russia went to war in Georgia. The United States was deeply enmeshed in Iraq and Afghanistan, and it made clear it had no intention of intervening. Limited by its commitment elsewhere, it was not in a position to rush troops there, though it did bring other forces such as sanctions to bear. After the war, the United States sent troops to Georgia, primarily to train the Georgian army, and its presence and commitment have lasted to this day.

It was a far slower response than it would have been during the Cold War, but it was no less significant. The question of why Russia’s actions should cause the U.S. to take risks and spend resources was still not challenged. A Russian threat to Georgia triggered a visceral reaction: Russian expansion must be blocked wherever it emerges, especially when the victim is America’s ally. The question of whether this even interests the United States was overridden by the assumption from the Cold War: The U.S. has a responsibility to stabilize the world.

The current dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh, a territory that like Georgia is located in the Caucasus, represents a fundamental shift in U.S. policy. Azerbaijan lost the territory to Armenia in the early 1990s. Since then, its recovery was a fundamental wish of Azerbaijan, but other internal issues preoccupied its time. But last week, the Azerbaijani military began an artillery attack that lasted for days. Armenia has refused to cede the territory. Turkey has sided with Azerbaijan, both because of historical affinity for Azerbaijan and because of long-standing hostility to Armenia. The Russians are allied with Armenia but also had close relations with Azerbaijan. The Iranians gave lukewarm support to Azerbaijan but overall made it clear that they wished to remain out of the conflict.

If there was an automatic assumption that the U.S. had to “manage” a crisis such as this in 2008, in 2020 it is apparent that the crisis is unmanageable. For one thing, who owns Nagorno-Karabakh is not a matter that concerns the U.S. For another, the outcome of a war – if it comes to that – would have minimal effect on the U.S. Last, U.S. relations with Turkey and Russia are already frayed, and the risks of navigating a war in the Caucasus would outweigh the benefits. Hence why Washington has offered only expected platitudes since last week.

The shift of U.S. strategy was inevitable and predictable. During the Cold War, it took the (not unreasonable) view that the world was of a single fabric such that it couldn’t stand by if it was being tugged far afield. In time, the Cold War ended but the strategy did not, as evidenced by bombing campaigns in Serbia and Libya. During this transitional period, it became much more difficult to define U.S. goals, and more difficult still to explain how military action would achieve the goal. The U.S. had spent half a century built around the principle of constant and urgent global involvement. Strategic principles die hard.

The United States is still singularly powerful, but the experience of war and hostile diplomacy can be painful even for the strong. There was a connection between U.S. power and risk in the Cold War. There is precious little connection between this and the future of Azerbaijani-Armenian relations. It’s the recognition that there is no global war underway, and that some things simply mean more to the U.S. than others. In a tiny place that few outside the region have heard of, the new necessity and logic of U.S. foreign policy are being carried out. In a way, that makes the U.S. more like other powers, accumulating political capital and spending it after calculating the risks of and rewards for acting.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East