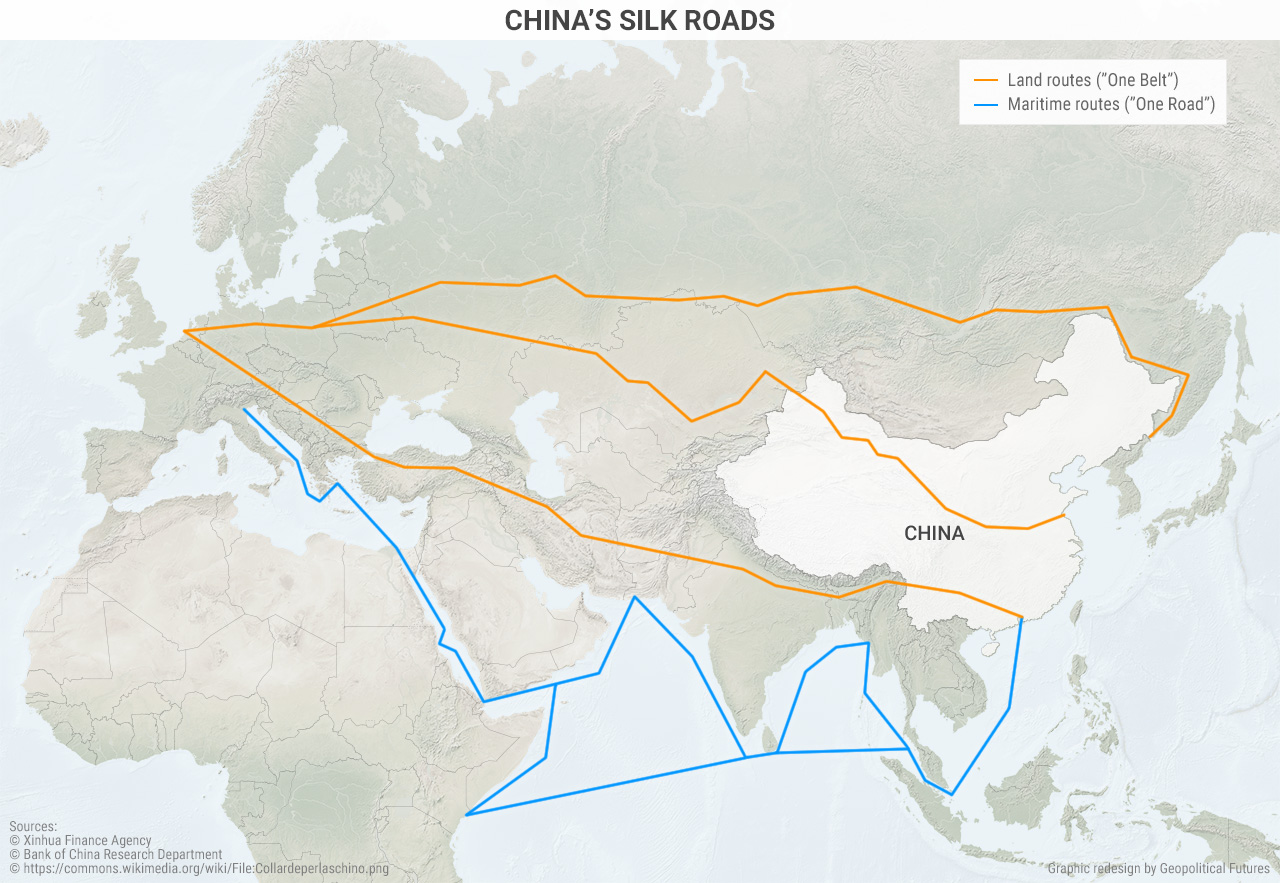

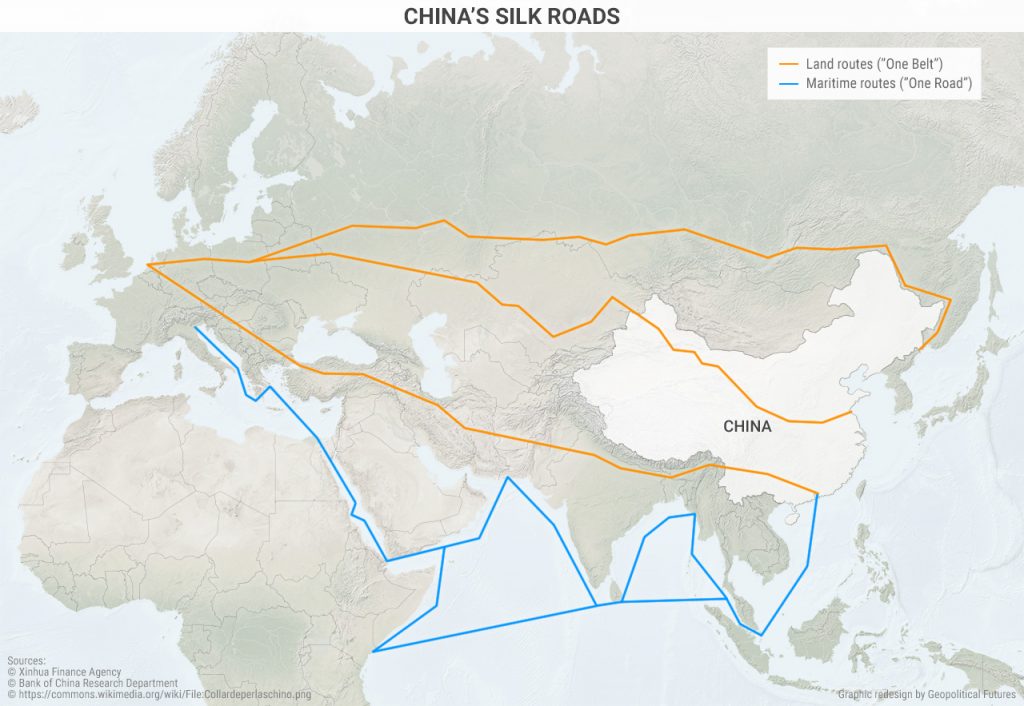

The One Road component of the initiative is China’s vision of a new Maritime Silk Road. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, roughly 80 percent of global trade by volume and over 70 percent of global trade by value is conducted by sea.

The One Road portion of OBOR is meant to increase Chinese construction of ports in countries along maritime routes that are already used in seaborne trade. China has already seen this strategy pay some dividends, having been awarded contracts to build ports in Myanmar and Sri Lanka. China also, however, has had some setbacks; a deal Beijing had with Bangladesh fell through in 2016 when Dhaka decided that an offer from Japan to build a port better suited its needs.

From a U.S. perspective, the importance of China’s projects along the Maritime Silk Road is significantly overinflated. Constructing ports will not provide China with permanent bases for Chinese destroyers or armies – the countries in question have yet to agree to host them. More important, the Chinese navy, despite its impressive advances over the past 25 years, is not capable of extended, long-term deployments in countries far away from the mainland.

OBOR ultimately matters relatively little. The initiative itself is ill-defined and has produced little of tangible importance in the three years since it was announced. Any successes achieved through OBOR do not threaten to upend the global balance of power.

For China, OBOR is about weaknesses in its domestic economy and about increasing its national prestige so as to appear more powerful than it is. China has already succeeded at the latter, but if OBOR is to be truly transformative, it must help China deal with the former, and whether it can remains an open question.