By Jacob L. Shapiro

China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy said in a statement on Dec. 15 that a Chinese carrier battle group, centered around the CNS Liaoning ship, carried out its first ever live-fire exercises. On Tuesday, the Center for Strategic and International Studies published a report that provided satellite images indicating China was placing anti-aircraft guns and probable close-in weapons systems on Chinese outposts in the Spratly Islands, though the specific systems could not be identified based on the images. On Dec. 14, an editorial published by the Global Times, an English-language Chinese newspaper, said, “It might be time for the Chinese mainland to reformulate its Taiwan policy, make the use of force as a main option and carefully prepare for it.”

China’s response to U.S. President-elect Donald Trump’s phone call with Taiwan’s president was measured at first. China cautiously observed developments and expressed its displeasure, but overall China went out of its way not to stir the pot too much. The above incidents suggest that China is beginning to find its voice again. Fielding a carrier battle group for the first time might on the surface suggest a large step forward in Chinese naval capabilities. New anti-air and anti-missile weapons systems in the Spratlys might suggest significant advances in Chinese defensive capabilities. And the ominous quote in the Global Times might be a sign that China is making the preparations necessary to seize Taiwan by force. The reality is much less exciting in all three cases.

This file photo taken on Sept. 24, 2012 shows China’s first aircraft carrier, a former Soviet carrier now called the Liaoning, docked after its handover to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy in Dalian, in China’s Liaoning province. STR/AFP/GettyImages

China’s Liaoning aircraft carrier is a refurbished Ukrainian ship that was commissioned in September 2012. That China has officially begun live-fire training exercises with Liaoning is a step forward in China’s technical capabilities. The problem for China is that it is a step forward from a starting point of essentially zero when it comes to fielding carrier battle groups. The Liaoning was not domestically built. The carrier China is currently building domestically will not be completed for years and will not represent a significant step forward in the Liaoning’s capabilities. By comparison, the U.S. has 10 carrier strike groups, five of which are currently underway. The Liaoning is significantly smaller than U.S. aircraft carriers and can host fewer combat aircraft – it can support around 36 aircraft; the typical U.S. carrier can host around 70.

China’s more serious problem is that this is its first live-fire exercise with a carrier battle group. According to the U.S. Department of Defense, China only graduated its first cohort of domestically trained pilots to fly China’s carrier-borne J-15 fighter jets in 2015. The Office of Naval Intelligence points out that China is still at least “several years” away from fielding fully integrated carrier air regiments. It also has not yet developed the kinds of ships that make up a strong carrier battle group, like guided missile destroyers, frigates and replenishment-at-sea ships. China has made some progress in producing these types of ships, but not enough. Beijing also does not have any experience integrating these complex parts into a unified strike group (the fact that the Chinese reports and pictures from the exercises did not indicate the specific types of other ships involved is perhaps notable in that regard). It is possible to be impressed with China’s progress while keeping in mind that what China has done this week equates to riding a bicycle with the training wheels on for the first time.

The publication of new satellite imagery of various anti-air and anti-ship defense mechanisms in the Spratly Islands is also overhyped, and not just by China. The head of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Command said on Wednesday that the U.S. would not allow sea lanes to be closed by China, “no matter how many bases are built on artificial features in the South China Sea.” The first thing to keep in mind is that China cannot afford to have sea lanes shut – exports are still the lifeblood of the Chinese economy, and China is not going to take an aggressive action that causes those sea lanes to be closed. Like the Liaoning, Chinese reclamation of these reefs and islands is more about prestige and image than about a meaningful increase in capability relative to the U.S.

From a strictly tactical point of view, China’s building projects in the Spratlys do not challenge the balance of power between China and the U.S. in the region. The RAND Corporation noted in a recent study that even if China is able to station military aircraft at Fiery Cross Reef and place surface-to-air missiles elsewhere, such facilities would not be a significant factor in a serious military conflagration between the U.S. and China. The U.S. could take out many of these targets with precision-guided munitions, and because the reefs are so small, China would be unable to keep enough stocks of fuel and munitions on the reefs should any conflict escalate. For a country like the Philippines, China’s activities in these areas are unnerving and might even pose a significant challenge – but they do not represent a challenge to U.S. naval superiority in the Pacific or the South China Sea.

Lastly, the article regarding use of force and Taiwan in the Global Times, which is connected to the Communist Party’s People’s Daily newspaper, indicates where China might be headed. China may indeed begin the process of preparing to use force. However, it will be many years, perhaps even decades, before China develops the types of capabilities needed to conduct an offensive operation aimed at reunifying Taiwan with the mainland. Taiwan has a significant military force of its own, and the superior power of the U.S. Navy would be brought into any potential conflict. China would not be able to achieve supremacy at sea or in the sky, both of which would be necessary for a successful amphibious assault or even a blockade of Taiwan for that matter.

Furthermore, amphibious assaults are extremely complex and difficult to execute successfully. China has little experience managing such operations, and a relatively small percent of PLA ground forces have gone through amphibious training. At the most basic level, China does not have the ships necessary to transport sufficient numbers of troops to a target like Taiwan. As recently as 2007, estimates were that the PLA Navy could only transport one mechanized division of troops over sea. Using force to achieve “reunification” would likely involve at least eight divisions, and that is a generous estimate that does not take support personnel into account. Since 2007, four ships of the new Yuzhao class have been commissioned, and while these represent a step forward in amphibious capability, it is far too small a step to suggest that China could conquer Taiwan. Any suggestion by China that it can take over Taiwan by force in the next decade is little more than a bluff.

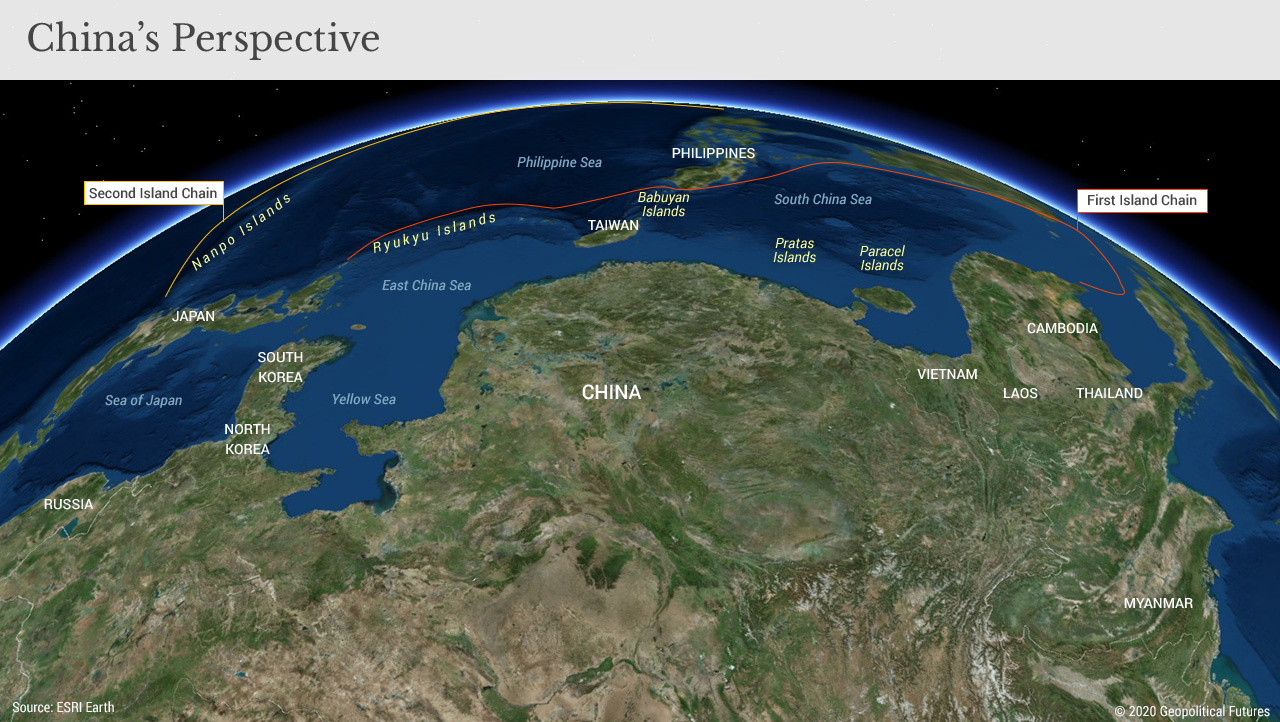

China is involved in a prestige offensive. It wants to give the impression that it is much more powerful than it is. China happens to be very good at this. What China has achieved in a relatively short time is impressive, and China is a significant regional power that is constantly improving its capabilities. But China remains constrained by its lack of current capabilities and experience. A spokesperson for the Chinese Defense Ministry responded to a query about Chinese facilities in the Spratlys by insisting it was all for self-defense, saying “if someone was at the door of your home, cocky and swaggering, how could it be that you wouldn’t prepare a slingshot?” That is actually a pretty good way of thinking about both China’s perspective and its current abilities.