One has to wonder what Jack Ma was thinking when, in a speech in Shanghai in late October, the Alibaba and Ant Group founder ripped into overzealous Chinese regulators, accusing them of having a “pawnshop mentality” and stifling innovation. Beijing promptly suspended Ant Group’s upcoming initial public offering, which was expected to be the largest in history, costing Ma personally an estimated $3 billion. Days later, Beijing unveiled sweeping new anti-monopoly legislation that will hit much of Ma’s sprawling empire.

That Ma’s comments struck a nerve was not surprising. As Chinese tech conglomerates like Ant Group have rapidly expanded into fintech and financial services, they’ve effectively become lightly regulated banks. And Chinese President Xi Jinping’s administration is obsessed with curbing financial risk. Though Beijing needs these companies’ innovations to get liquidity to corners of the economy that the Chinese banking system struggles to service, these inevitably make it more difficult to stave off a cascading financial crisis. When forced to choose between dynamism and stability, Beijing almost always chooses the latter.

Curiously, though, in the weeks that followed Ma’s comments, Beijing mostly sat on its hands when state-owned enterprises (SOEs) across multiple sectors began publicly announcing defaults on corporate bond obligations. Defaults by Chinese state-backed firms are exceedingly rare, given their VIP access to state credit. Thus, any hints that SOEs are about to default, or state banks about to fail, tends to push Chinese financial markets to the brink of panic. This came a week after Xi had praised Chinese SOEs as proving themselves even more reliable than their private counterparts in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, pledging to make them bigger, better and stronger.

The confluence of events speaks volumes about the high-wire path Beijing is walking to stave off a financial reckoning. But it also suggests that Beijing thinks it has found a model of state capitalism that lets it eat its cake and have it too.

The Problems

In 2017, Xi elevated financial stability to the level of national security in terms of the Chinese Communist Party’s priorities. There’s a good reason for this fixation: No country in history has amassed so much debt so quickly as China has without succumbing to a financial meltdown, according to the World Bank. So long as China’s economy was galloping ahead at double-digit growth, with the corporate sector awash in easy profits to paper over inefficiencies and an immature system for pricing risk, the chances of an uncontrollable financial crisis were low. But as the Chinese growth model shifted from one driven by exports and land liberalization to investment, and as gross domestic product growth entered into a long, if gradual, slowdown, the margin for error began to narrow considerably. Things became particularly hairy after the 2008 global financial crisis, when Beijing unleashed a staggering amount of stimulus, effectively giving local governments a blank check, and then found itself incapable of scaling back without sending the entire system into a tailspin.

Since 2017, Xi’s administration has attempted to implement a suite of ambitious “de-risking” reforms. These have included overhauling the regulatory apparatus, sending the anti-graft authorities after wayward officials and tycoons, and hammering local and provincial governments and banks to clean up their books and eschew “shadow lending” practices. It also gave the central bank free rein to tinker endlessly with the system in search of an elusive balance between liquidity and control. But this effort has been bedeviled by two chronic problems, both a result of Beijing’s insistence on maintaining a state-centric system.

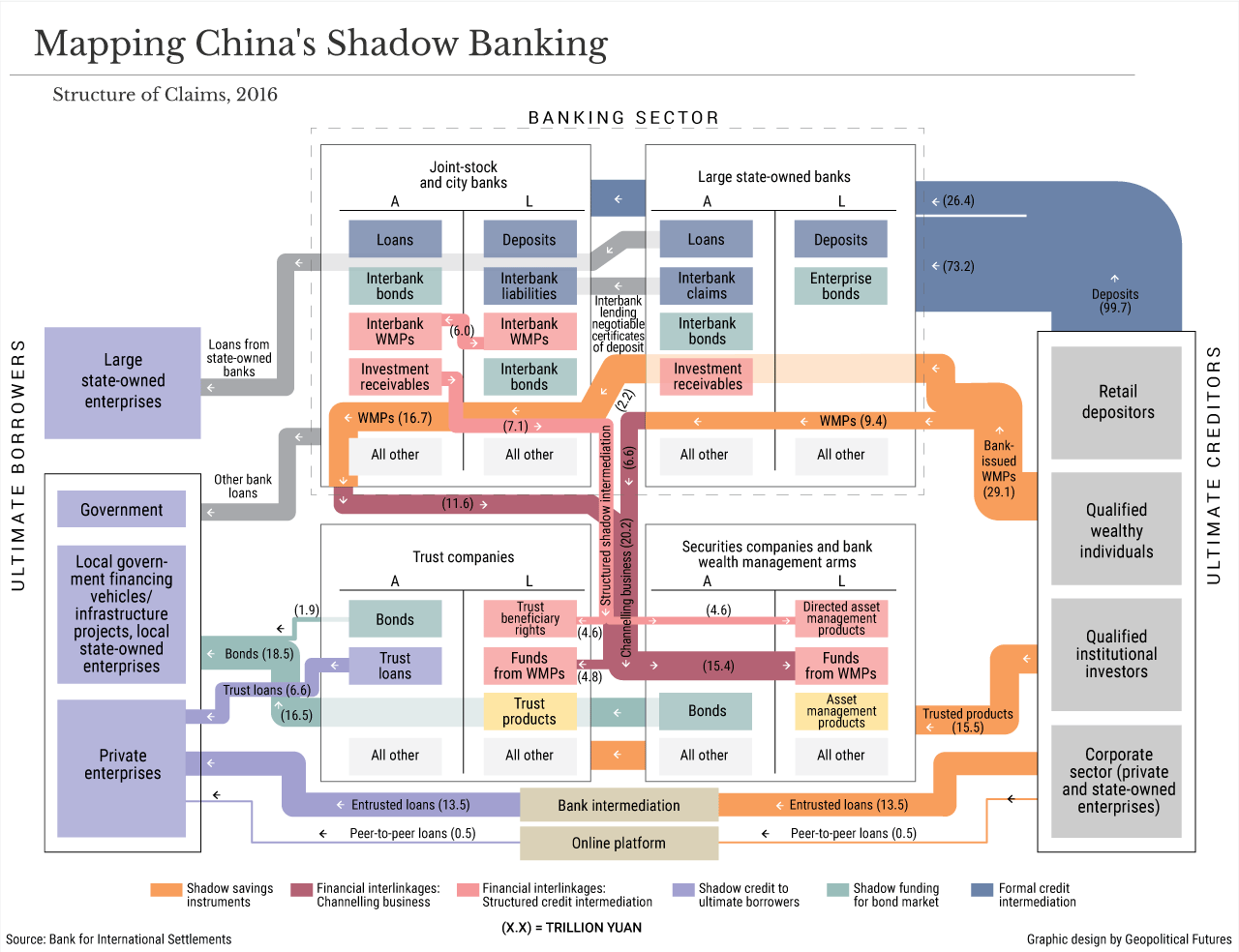

One is a distorted banking system that’s heavily incentivized to focus on the needs of China’s more than 150,000 SOEs (the bulk of which are owned by provincial and local governments) and projects that banks suspect will be prioritized by the party – and thus guaranteed not to bust – at the expense of everything else. As a result, the system is not particularly good at pricing risk or distributing credit to areas of the economy that don’t have implicit state backing. It’s particularly bad at meeting the needs of households and small and medium-size enterprises, which tend to have scant credit histories or assets available for collateral but which now make up the overwhelming share of employment in China. This forces businesses and cash-strapped local governments to seek funding via shadow lending vehicles (the opacity of which makes Beijing nervous) and households to rely on things like peer-to-peer lending platforms (the volatility of which makes Beijing very nervous as a potential source of social upheaval). It also created an opening for fintech firms like Ant Group to fill the void in consumer-facing finance.

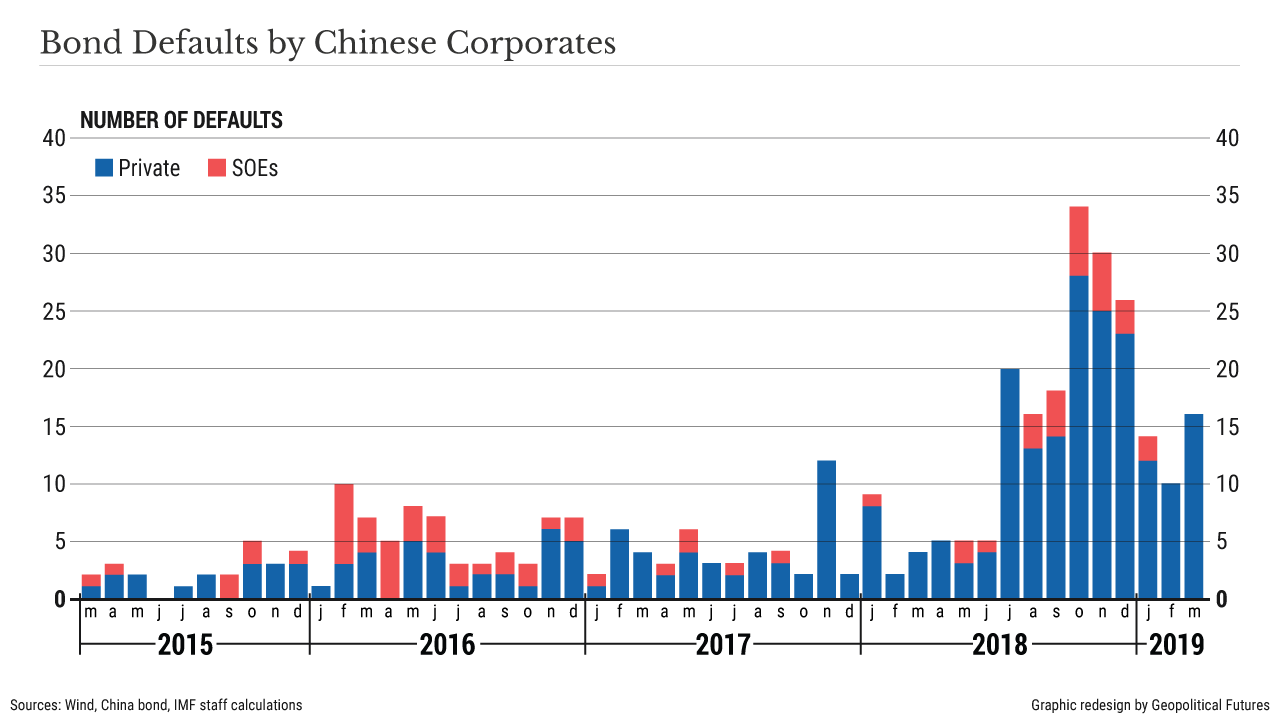

All this forces regulators to tread carefully when implementing new de-risking measures. Move too far, too fast, and the private sector may face a credit crunch – as it did in 2018 and 2019, even before the pandemic – and China’s cherished growth may grind to a halt. Move too slow, and household savings – the great stabilizer and safety net of the Chinese economy – may fall away, speculative real estate bubbles may pop, and any number of interlocking fault lines may rupture at once.

The other core problem is moral hazard. Put simply, given Beijing’s existential fear of unemployment and social unrest, lenders and investors understandably just assume that the state will more often than not come to the rescue if things go sideways and pose any degree of systemic risk. Beijing also realizes that if people think that the state is guaranteeing their deposits or investments, and the state doesn’t live up to its promise (implicit or otherwise), people are likely to direct their ire not at poorly run banks or companies but at the state itself. Naturally, this encourages all sorts of risky lending and investment activity. This is particularly true with SOEs and state banks. Beijing sees such entities as invaluable tools for soaking up surplus employment and funding or carrying out projects prioritized for social development or diplomatic goals, as well as for brokering factional peace and deepening dependence on the party’s goodwill. It is willing to tolerate a lack of profit and efficiency in the state sector in service of these ulterior goals. Local governments, meanwhile, rely on the state firms they control to get around regulatory constraints and meet employment and growth targets set from above.

Regulators may grouse about the state sector’s profligate ways, but they’ve generally been unwilling to expose it fully to market forces and leave state banks, in particular, on the hook for losses. The handful of times they’ve tried, things have gone badly. The closest China has come to having its own Lehman Brothers moment was in June 2013, for example, when Beijing briefly declined to intervene following a technical default between two small banks. This sent interbank lending rates soaring, grinding lending to a halt and sparking a liquidity crisis that began to spread into the rest of the economy. Beijing quickly backed down, and the merry circus continued.

The Solutions

The past month’s events are just the latest iteration of this push and pull between market and state. But, as is usually the case with China, it’s always difficult to discern whether unusual developments are a sign of Beijing’s weakness or strength. Does the crackdown on tech conglomerates betray a growing fear in Beijing that their growing wealth and control over data and information (things the Communist Party of China wants to monopolize) will translate into political power and rupture China’s historical regional and socioeconomic fault lines? Or is Beijing merely flexing in service of a prudent policy? (Ant Group quickly acquiesced, after all.) Does letting SOEs default suggest that the scale of China’s debt woes is surpassing Beijing’s ability to respond, or has Beijing’s financial de-risking campaign been so successful that it feels it’s high time to teach profligate state-owned firms a thing or two about accountability?

In most cases, there’s an element of both. A permanent sense of intertwined crisis and opportunity is the foremost driver of the Communist Party’s behavior. But what’s different this time around is that Beijing appears to truly feel that its measures are working. The pandemic was the ultimate stress test of the Chinese system. And the system by and large has emerged unscathed – even stable enough to risk a market panic by letting SOEs fall on their swords or to risk another liquidity crunch by saddling fintech innovations with new regulations. It’s done this without resorting to 2008-style stimulus. It’s done this while cracking down on Hong Kong despite the risk of scaring off much-needed foreign investment. It’s done this as the focus of U.S. economic pressure on China has shifted from trade to finance.

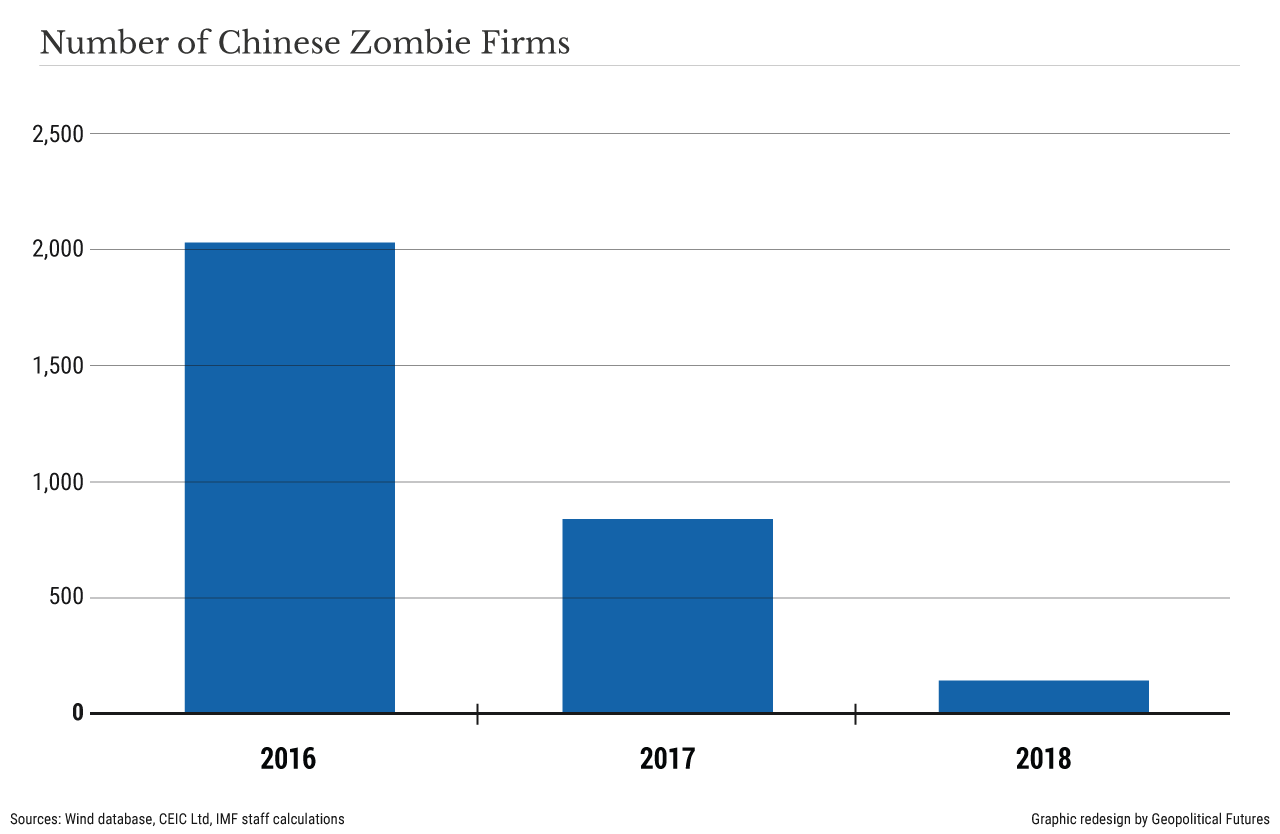

Indeed, Beijing thinks the pandemic, like the 2008 global financial crisis, has in many ways illustrated the superiority of the Chinese approach to financial stability – or at least what Beijing hopes the system will become, with some additional technocratic tweaking, some purging of corrupt elements and regular injections of party ideology to get everyone marching in the same direction. And to be sure, Beijing deserves credit for empowering its regulators to take on painful reforms before the crisis hit and for implementing a countercyclical regulatory system designed to adjust on the fly, tightening and relaxing control as changing conditions demand. It can count real successes in curbing shadow lending and shutting down “zombie enterprises” in a relatively controlled manner. What the system lacks in market incentives to act prudently, Beijing has been able to offset, to an extent, by introducing fear of Xi. Perhaps this is one of the benefits of living in constant fear that an existential crisis is just around the corner – you’re far less likely to get caught flat-footed.

The core contradictions embedded in China’s model remain, though. It’s unlikely to ever embrace a cleansing but potentially destabilizing recession. It’s not about to reduce the role of state banks and enterprises. It’ll remain enormously difficult to weed out moral hazard altogether, and to persuade financial institutions to act against their own self-interest, so long as it sees a state-centric economy essential for party survival. There’s an inevitable trade-off between dynamism and control. Even if this model remains adept at staving off a cataclysmic crisis, a long slowdown will be hard to avoid. In other words, China’s financial reckoning probably can’t be avoided forever, but it’s likely to look a lot more like Japan’s Lost Decades than what was faced by South Korea and much of Southeast Asia during the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Given what the consequences of the latter would look like in China, it’ll happily make that trade.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East