By Allison Fedirka

Mixed messages have been coming out of Australia this week regarding Canberra’s threat perception of China. The defense minister, for example, changed her position on the threat from Beijing overnight. Initially, she said that Australia shared similar concerns as the U.S. National Security Strategy – which points to China’s expanding military as a top security priority. Later, she backtracked, saying Australia doesn’t see China as a threat. Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and Foreign Minister Julie Bishop also chimed in, saying China does not pose a military threat to Australia. This was soon followed by the deputy director of the Australian Security Intelligence Organization, claiming that China posed an extreme threat to Australia, particularly in the area of espionage. The rhetorical back and forth is nothing new and is symptomatic of how Australia’s immediate economic needs can be at odds with its longer-term strategic objectives.

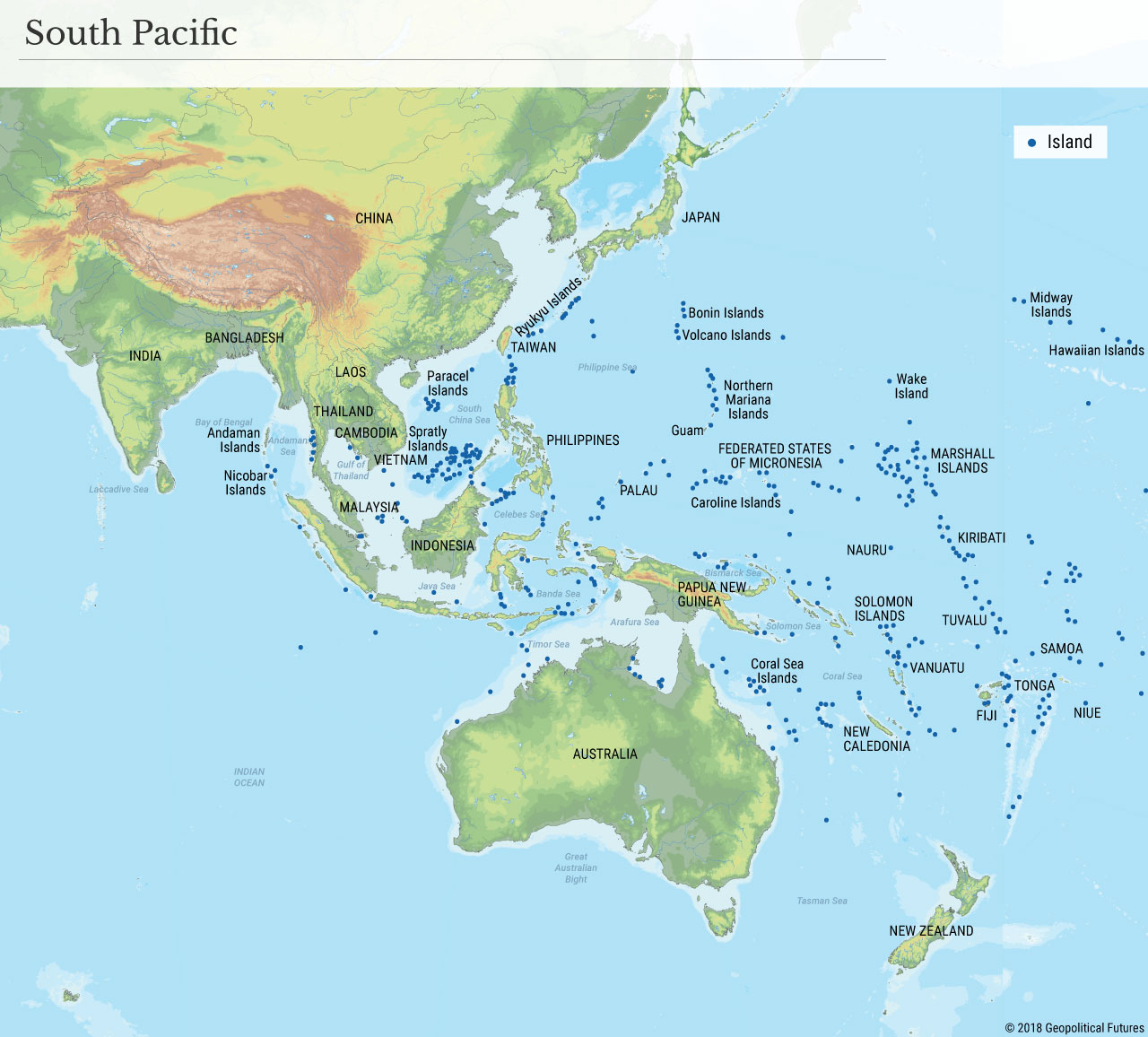

Canberra is questioning whether it should shift its focus from the United States to Asia. The pull Australia feels between China and the U.S. was captured in the government’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper. In the document, the Australian government identifies the U.S.-China relationship and its effects on the Pacific region as the source of Canberra’s main challenges. Australia’s main goal, and challenge, is to protect global shipping lanes so that the island nation’s imports and exports can move freely throughout the world. Located in the Southern Hemisphere, the country is on the periphery of major maritime trade routes. It has a small population – especially compared to its landmass – and a very long coastline, which limits the country’s military capabilities.

Australia, as a whole, is an inhospitable environment for large-scale human settlement and is therefore unable to meet all its needs domestically. It has always relied on outside powers for this – both to secure sea routes and to spur economic activity through trade. It is here that U.S.-Chinese relations intersect with Australia’s international interests. It needs strong trade and business partners as well as a strong military alliance to protect trade flows. The current dilemma for Australia arises from the fact that its top trading partner, China, is locked in an intensifying rivalry with the United States, Australia’s security patron. The conflicting statements from Australian officials reflects this uneasiness about needing to work closely yet separately with two countries that are increasingly distrustful of one another.

The question over which side Australia should align itself with has been simmering for a couple of years. Much of Australia’s media and many politicians have raised questions about Chinese immigration, influence and espionage. Turnbull and other political leaders have gradually become more hawkish in their position against Chinese influence in Australia, particularly after reports of Chinese money being used to sway Australian political campaigns and policy. There has also been a clampdown on Chinese investments in Australian real estate, ports and farmland.

In the past year, the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump has cast doubt on the U.S. commitment to the region. After mere days in office, Trump threatened to renege on a deal the U.S. government had with Australia to resettle Syrian refugees. Shortly after, Washington pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a 12-nation trade deal that included Australia. The situation in North Korea – its nuclear weapons program and the threat that poses to the U.S. – also gives Australia pause since a major military conflict could compromise Washington’s ability to honor its security commitments. The U.S. still needs Australia to maintain a strong foothold in the region and is by no means turning its back on it. But domestic issues have made U.S. foreign policy erratic, and that makes an ally like Australia uncomfortable.

Two Strategies

To help manage its relationships with China and the United States, the Australian government is pursuing two strategies. Regarding China, Canberra is keeping the focus heavily on business ties. China’s economy requires massive amounts of commodities to stay running, and Australia’s coal and iron ore exports (among others) have largely benefited from this. During and after the 2008 financial crisis, Australia pulled back from antagonizing China. Since then, Canberra has seen the value of keeping the focus on wealth generation and maintaining a steady relationship with Beijing.

As for the United States, the Australian government has demonstrated a willingness to expand its security relationship with the U.S. to include regional allies such as Japan and India. Some of the most recent examples include Australia’s support for reviving the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, an informal coalition involving the U.S., Australia, Japan and India, and a bilateral agreement between Japan and Australia that significantly enhances the transfer of military hardware between the countries and the training of Japanese troops in Darwin. Such moves show commitment to the United States while at the same time strengthening defense ties with other nations. The government’s labeling in the Foreign Policy White Paper of its “neighborhood” as the Indo-Pacific region reflects the emphasis Canberra places on its on ties with Japan and India to help secure its interests in the Pacific. As Beijing continues to encroach on the South China Sea – which Australia is less reliant on due to its geographic position – Australia needs to maintain open trade flows and therefore must have a security alliance capable of ensuring sea lanes remain accessible. That means it still needs the United States, but it is increasingly also looking to regional allies for support, should U.S. engagement in the region wane.

For Australia, the dilemma ultimately comes down to the fact that its key security partner is at odds with its top economic partner. This is a relatively new scenario for Australia, since up until 2007 its top trade partners were also aligned with its top security partners. From the early 1900s through the first half of the 1960s, the United Kingdom was Australia’s top trade partner. Then, from about 1965, Japan replaced the U.K. as the leading trade partner. In 2007, China assumed the title. All the while, the United States ranked as Australia’s second- or third-largest trade partner. (It’s currently a close second.) On the security side, Australia initially used its colonial ties to rely on the U.K. After World War II, the United States became Australia’s top security partner (and Japan came under the U.S. security blanket as well). The U.S. and the U.K.’s long-standing alliance with Australia is seen through their involvement in organizations such as the Five Eyes, an intelligence-sharing program that also includes Canada and New Zealand, and coordinated, international military missions in places such as Afghanistan and Syria.

Security vs. Economy

It is not uncommon to see nations re-evaluate their partnerships to make sure national interests are still being served by them. At this point, Australia is looking at the possibility of choosing between security and economy. Ultimately, it will side with the United States for two reasons. First, when a country is forced to choose between the two, security will trump economy. This is particularly true for Australia, where security plays an integral role in ensuring the health of the economy. The other reason is that while China plays a major role in Australia’s economy, Canberra has the world’s top economy (U.S.), and third- and fifth-largest economies (Japan and the U.K.) to fall back on, not to mention the budding security relationship with India, whose economy ranks seventh. Australia’s uneasiness with this new dynamic is understandable even if it does not pose an existential threat.