Russia and Canada also have the largest naval fleets equipped to deal with the Arctic’s harsh climate. Russia has over 40 icebreakers in its fleet, while Canada has 15. By comparison, the United States has only two functional ice breakers, and though it could build more, it would take 5-10 years.

It is tempting to say that Russia already dominates the Arctic – that its power there exceeds even that of the United States. Certainly, thinking like that is part of the reason for the sensationalist reporting about Russia’s military modernization campaigns and its increased deployment of military assets in its territory in the region.

It is true both that Russia is seeking to modernize its military forces and that it has dispatched forces in greater numbers to the Arctic, though the size and abilities of those forces still pale in comparison to what Russia had stationed in the area during the Cold War. More important, however, this type of view of Russian behavior in the Arctic misreads the geopolitical reality of the situation. The West tends to view the Arctic as a potential source of Russian strength; in reality, it is more of a Russian vulnerability.

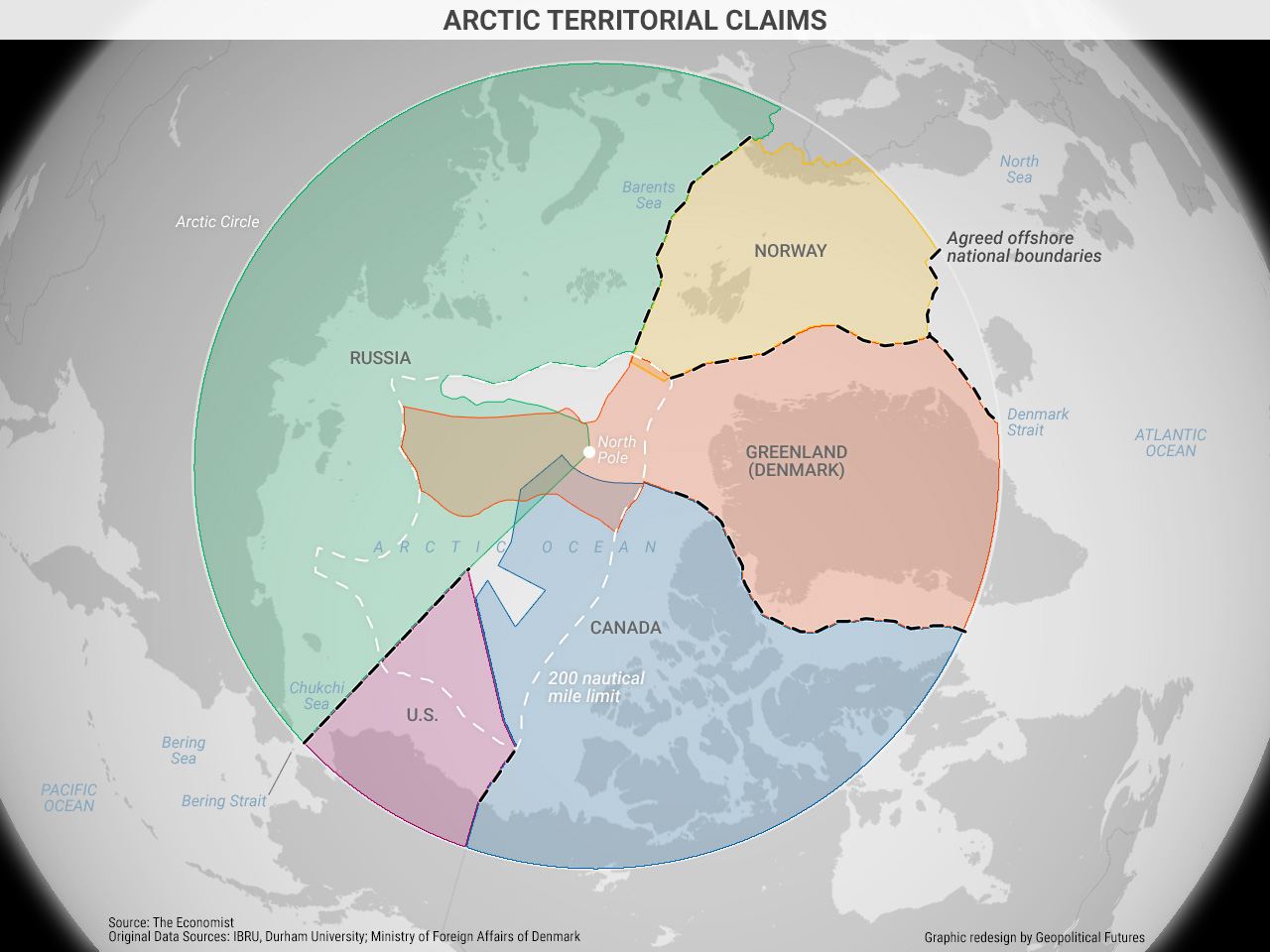

This week’s graphic shows the Arctic region from above. What immediately jumps out is that Russia’s vast holdings of territory in the Arctic do not help it deal with one of its fundamental strategic weaknesses: its lack of access to the world’s oceans. Russia cannot exit the Arctic to get to the Pacific without passing the Chukchi Sea and the Bering Strait, both of which are off the coast of Alaska.

The U.S. may not have many ice breakers, but the rest of its navy is without peer and could easily shut down this shipping lane if it deemed it in its national interest to do so. To exit the Arctic Ocean to the Atlantic, Russia would have to traverse the waters between Iceland and Greenland, or between Iceland and the United Kingdom. These are larger openings than the Bering Strait by far – about 200 and 500 miles, respectively – but they are still eminently susceptible to a blockade from anti-Russian forces.

Russia’s position in the Arctic, then, is something of a trap. If the U.S. so chose, it could block traffic coming into and out of the Arctic, and there is little Russia could do to retaliate. Furthermore, increased accessibility to the Arctic opens the Russian heartland to a vulnerability it has never had to face before.

The core of Russian strategy in Europe has been to establish buffer zones between Moscow and the North European Plain. This strategy is based in part on the idea that Russia has not had to worry about a potential threat to its long Arctic coastline, the Arctic being impossible for its enemies to traverse. If Arctic ice melts enough to allow trade in the Arctic Ocean year-round, that also means that enemy naval forces would have more room to operate. This explains why Russia has assumed such a defensive posture in the region.

The Road to 2040

The Road to 2040