By Jacob L. Shapiro

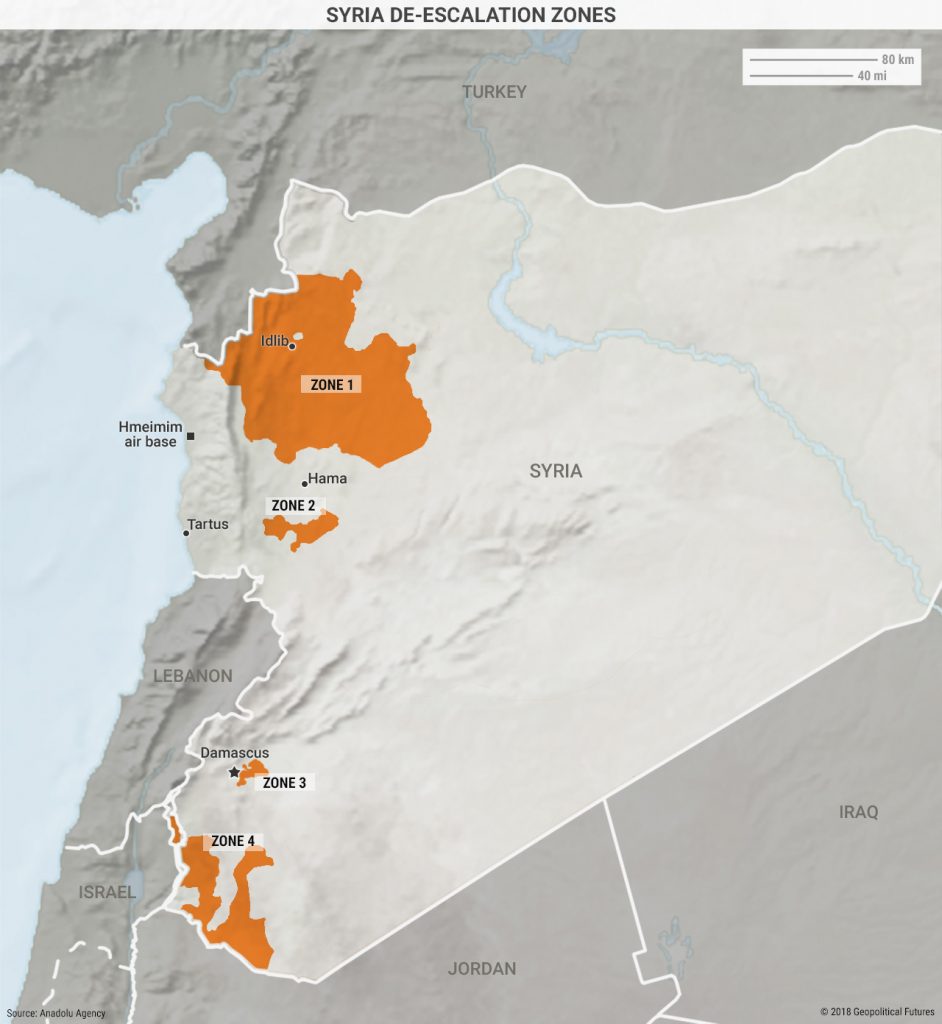

The “Astana troika” is in danger of breaking up. After meeting in Astana, Kazakhstan, in mid-September, Turkey, Iran and Russia agreed to serve as guarantors of a cease-fire agreement in Syria. Four “de-escalation zones” were established with the goal of a six-month pause (subject to further extension) in fighting between the forces of Syrian President Bashar Assad’s regime and anti-government rebels in these zones. The problem with this arrangement is that these countries don’t see eye to eye. Turkey supports the anti-government rebels. Russia and Iran support Assad’s regime. Now the two sides are accusing each other of supporting their favorites rather than keeping the peace.

On Jan. 9, the Turkish Foreign Ministry summoned the Russian and Iranian ambassadors to express its concerns over the Assad regime’s advances in the Idlib de-escalation zone, the largest, most strategic and most contested of the four zones. The next day, Turkey’s foreign minister pointed the finger at Russia and Iran, insisting that Turkey’s two purported partners needed to do more to stop the Syrian regime and fulfill their duties as guarantors of the cease-fire. The same day, Yeni Safak, a Turkish newspaper known for its strong support of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s government, claimed that the Assad regime’s advance was coordinated with the Islamic State, with the tacit support of Russia and Iran. Turkey likes to accuse all its enemies of being in cahoots with IS, but Russia and Iran aren’t supposed to be enemies. That makes the report notable, regardless of its admittedly dubious veracity.

This isn’t the first time Turkey has had cause for concern about the actions of Russia and Iran. On Dec. 20, Reuters reported that the Syrian army, backed by Russian air support, had seized 50 villages in southern Idlib province the previous week. On Dec. 25, Anadolu Agency reported Syrian and Russian airstrikes in both Idlib and Hama provinces. On Jan. 7, TRT reported additional airstrikes in Idlib, and the next day, Anadolu reported that a Turkish military convoy in Idlib had come under fire from unknown assailants. And on Jan. 10, Syria’s state-run news agency SANA reported that Syrian government forces and allies had captured 23 new villages in the Idlib countryside.

Different Points of View

From Turkey’s perspective, the Assad regime, with Russian air support and Iran’s blessing, is attempting to assert its control over territories currently held by anti-Assad regime rebels. The victims of this offensive are civilians and moderate opposition groups that Turkey has pledged to defend.

Russia, for its part, does not accept that the terms of the cease-fire apply to all elements of the opposition. The dominant militia in Idlib is Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, a jihadist group whose core element is al-Qaida’s Syrian branch. Russia views HTS as a fair target and is encouraging the Assad regime to attack HTS fighters wherever they hold territory. HTS strongholds happen to be in Idlib, so that is where Russia is concentrating its resources. Eliminating jihadists, from Russia’s point of view, is a necessary part of maintaining the de-escalation zones. Furthermore, Russia expected Turkey to put pressure on HTS to give up its arms and disband when its forces entered Idlib province. Turkey has declined to do so, at times even collaborating with HTS on the ground, giving Russia the pretense it needs to support further Assad regime consolidation efforts.

It’s important to keep in mind that none of this was Russia’s preferred outcome. Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the defeat of IS and the imminent withdrawal of Russian troops from Syria on Dec. 6, in part because he calculated that conditions were ripe for a political solution to the Syrian civil war. Putin’s political solution and the triumphant recall of Russian troops now seem a distant memory. On Dec. 31, at least two Russian soldiers were killed when Hmeimim air base was shelled, reportedly by jihadist militants. Russia disputed reports that a significant number of its planes were damaged in the attack. Then, on Jan. 6, 13 unmanned aerial vehicles attacked the base at Hmeimim and a logistics center at Tartus. According to Russia’s Ministry of Defense, the attacking UAVs were neutralized. The two attacks have underscored just how far Russia is from being able to pull out its forces, and how vulnerable its forces are to attack.

Russia has since made a point of providing two more details about the Jan. 6 attack. On Jan. 8, the Russian Ministry of Defense said the UAVs were of such sophistication that they “could have been received only from a country with high technological potential on providing satellite navigation and distant control of firing.” In other words: the United States. (The Pentagon has rejected these claims as ludicrous and noted that IS regularly uses primitive UAVs to attack U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces fighters in eastern Syria.) Then, on Jan. 10, the Defense Ministry’s newspaper published a report that said the UAVs had been launched from Muazzara in southwestern Idlib. The report said that this territory was under the control of “moderate opposition” forces backed by the Turkish government and that Russia had sent a formal complaint of its own to high-level Turkish officials exhorting them to ensure Turkey enforced the cease-fire.

Iran Leans Toward Russia

Iran has not made its views known on this particular incident. The presence of Iran’s foreign minister in Moscow on Jan. 10, however, as well as its own military support of Assad’s advances in Idlib, indicate that Iran’s views are more closely aligned with Russia than with Turkey on this matter, which only makes sense. Though Turkey and Iran have some interests in common, they diverge in Syria, despite prior short-term tactical cooperation against Kurdish groups. Iran looks at the Assad regime as integral to its strategy to increase its power. Turkey views Iran as a long-term rival that has amassed an impressive strategic advantage in recent months and needs to be cut back down to size. Turkey also sees that Iran, at least for now, has tied its ambitions to Russia, another long-term Turkish rival.

Nevertheless, the “alliance” among these three countries was built on a mismatch of interests. It’s a perfect example of the old adage that two’s company, three’s a crowd. The more countries you try to cram into an alliance, the more tenuous the alliance becomes. It was one thing to coordinate moves when all sides could agree that defeating the Islamic State was the main priority. But the defeat of IS eliminated the only common ground these countries had in Syria. Turkey’s ideal political solution sees Assad removed and the country stitched back together under Sunni aegis. Iran’s ideal political solution sees Assad restored but dependent on Iran and its proxies for survival. Russia’s ideal political solution is any that makes it appear strong and keeps Assad as a somewhat independent actor, neither dependent on Tehran nor fearful of Ankara’s next move. Something’s got to give.

Now these fissures are coming out into the open, just a week before representatives of Iran, Turkey and Russia are to meet to plan the Sochi Congress on Syria’s Future, scheduled for Jan. 29-30. Even the preparations for this meeting have been tense, with some Syrian opposition groups refusing to attend and Turkey insisting that it will not attend any meeting that includes the YPG, the militia representing Syrian Kurds. Russia reportedly had invited YPG representatives in October but backed off when Turkey objected. Syrian Kurdish officials insisted as recently as two weeks ago that Moscow has promised them an invitation, while Turkey maintains that Russia has agreed not to do so. Russia, for its part, has a history of supporting anti-Turkish Kurdish groups when it’s strategically useful to keep Turkey distracted.

Regardless of who attends the Sochi meeting, Syria’s future will not be decided there, or in Astana or Geneva or Timbuktu. It’s being decided on the ground in Syria right now, and it’s bringing Turkey into conflict, however unwillingly, with its historical rivals. The Astana troika may very well figure out a way to paper over these inconsistencies during the meeting in Sochi, but it’s all a charade. On the ground, the Assad regime has the upper hand and Russia is calling the shots, still very much at war. Iran is biding its time, hoping to capitalize on Russia’s eventual fatigue. Turkey finds itself backed into a corner but without the requisite strength to preserve its interests. It needs to stall, but angry comments to ambassadors won’t stop Assad or Russia, though they will produce nice headlines. Turkey is searching for a way to stop Assad, and if it can’t find one, it will be on the losing end of this breakup.