By Xander Snyder

South Africa should probably be more powerful than it is. It’s at the southern tip of the African continent, where it can relatively easily trade with Europe, Asia and the Americas. In terms of economic and military strength it is peerless in the region. It’s a world leader in the production and export of many types of metals and coal. Yet South Africa has not broken through as a country of great geopolitical relevance. It is the wealthiest country in Africa in absolute terms, but it is still extremely poor, and divisions – economic, racial and tribal – keep it focused inward.

Many hope that Cyril Ramaphosa, who was elected president of the African National Congress on Dec. 18, will change South Africa’s fate. Ramaphosa, a close associate and ally of Nelson Mandela throughout his decades-long battle against the Afrikaner government, replaced President Jacob Zuma at the head of the ANC, South Africa’s dominant political party. Presidential elections will not occur until 2019, but it’s extremely likely that as the leader of the ANC, Ramaphosa will win.

A major factor in the optimism about South Africa’s future under a Ramaphosa presidency is that he is independently wealthy. The thinking is that this would make him less subject to temptation and therefore less prone to the self-aggrandizement in which Zuma partook. This would, in turn, decrease the influence of people who have won lucrative state contracts through their personal connections. But for South Africa to reach its potential, it’s not as simple as changing the man at the top.

The Geopolitical Question

The geopolitical question of South Africa is why, despite its wealth, it has not emerged as a greater regional power. We have tackled this issue before, and suffice it to say the answer is not as simple as eliminating government corruption.

Take, for example, the case of the Guptas, a wealthy family said to have had frequent dubious dealings with Zuma. One estimate cited in the Financial Times reckons that the family has made profits of about $2 billion through its state contracts (over an unspecified duration). Assuming all of that is “corrupt” money (it probably isn’t) and that the cozy relationship with the Zuma administration spanned five years (it probably existed far longer), that equates to a high-end estimate of about $400 million per year. In a country with as much poverty as South Africa, such an amount would undoubtedly improve the lives of some. But the budget of South Africa last year was approximately $98 billion, which means that even this aggressive estimate of the Guptas’ personal gains would account for less than half of a percent of total government spending. Though the ramifications of preferential treatment of state contractors span beyond the purely economic, an additional half a percent of spending would not fix South Africa’s problems.

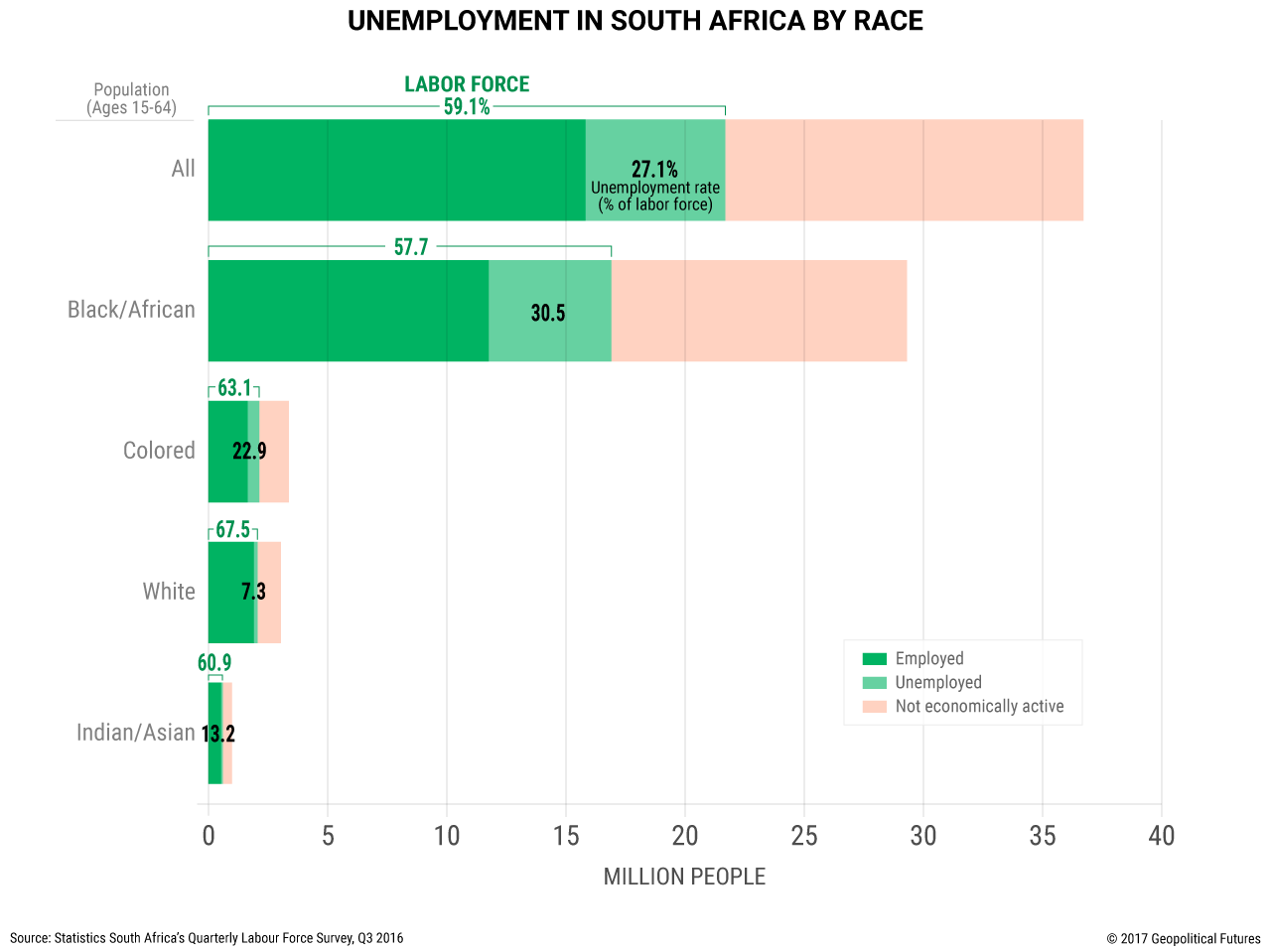

And the problems are legion. Wealth inequality, a holdover from the apartheid era, persists along largely the same racial lines as it did before Mandela became president. Access to education remains limited for South Africa’s black citizens, which affects not only economic growth but also the distribution of that growth among the population. Health care is not widely available, which results in a lower life expectancy for blacks than for whites. Access to basic services, such as water and electricity, has improved since the end of apartheid, but many people still live in isolated areas where jobs are far away and the lack of transportation infrastructure makes them even harder to reach. Power projection will be impossible as long as South African society is divided and the economy is non-inclusive.

Elusive Answers

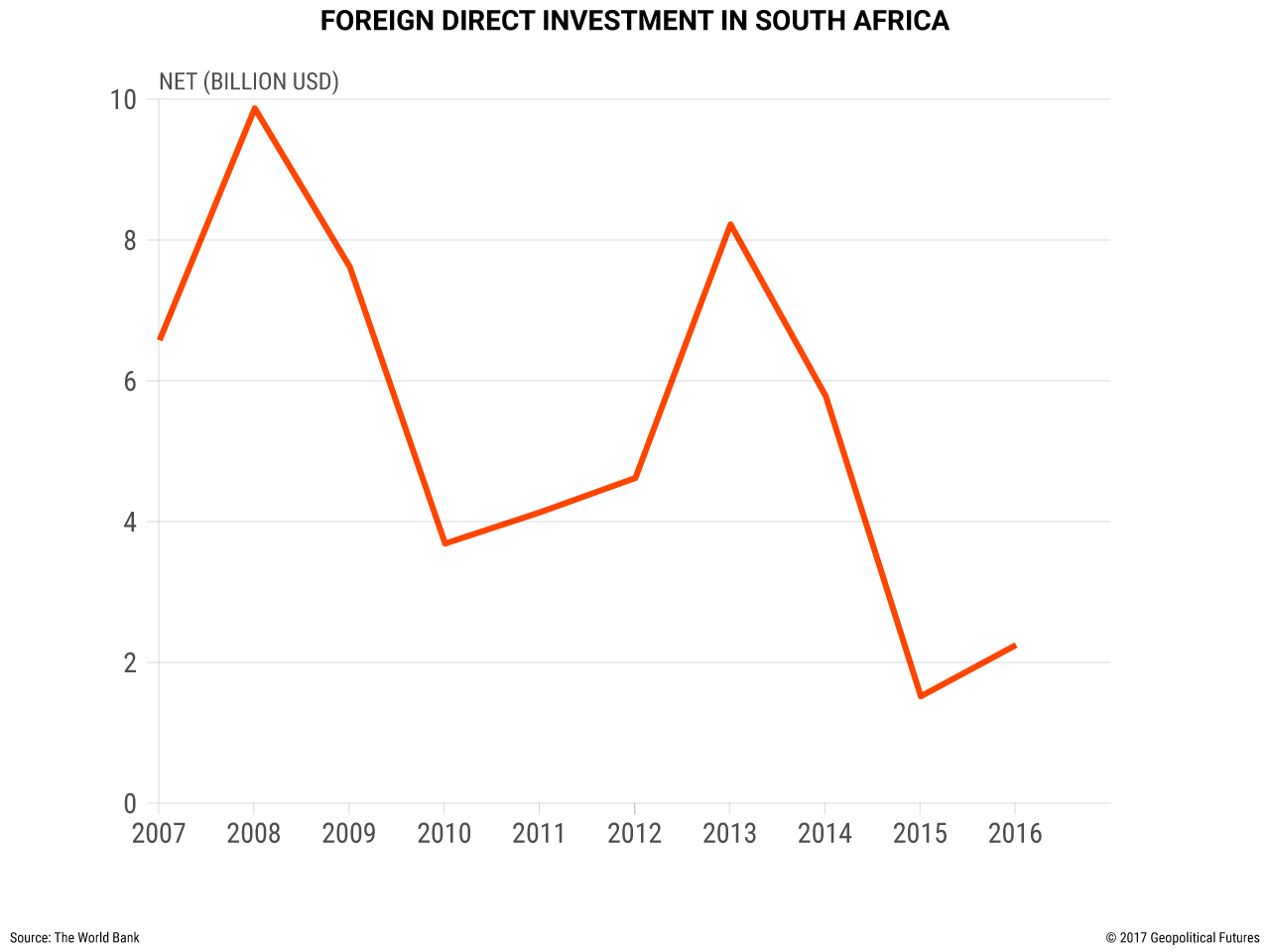

To overcome these issues, South Africa has two basic options: forcibly redistribute wealth or try to generate equitable economic activity and grow out of the problem. Wealth distribution is highly unlikely, not just because the constitution prohibits it – property protection was a major concession that Mandela had to make before then-President F.W. de Klerk would proceed with negotiations that ended apartheid – but also because the inevitable backlash discourages it. Asset seizures could spark violent resistance. It’s been done before, including in neighboring Zimbabwe, where the government confiscated the assets of white landowners. Large-scale asset seizures, however, would effectively isolate the country from international investment, as investors would steer clear out of fear that their own assets could be taken.

The second option, generating wealth among the poor, is easier said than done. Wealth generation among the non-wealthy requires a productive economy that employs most of the country’s population, which itself requires that population to have marketable skills. This is not the case in South Africa. The legacy of institutionalized racial segregation persists, creating a society that still encounters unequal access to opportunity decades after the formal end of apartheid.

Workers also must have physical access to jobs in order to work, which means either living in a city or having access to public transportation. Building public transportation requires infrastructure investment. Yet as the South African National Treasury candidly pointed out in its 2017 budget, the government’s “extensive responsibilities for infrastructure are now stretched to their limits.” There is not much the government can do, and the only alternative for capital right now is foreign investment, which has been declining since 2008.

It may be that the end of the Zuma administration marks the beginning of a new era of change in South Africa – but probably not. Deep, historically rooted obstacles will continue to hinder the country’s rise, regardless of the rectitude of its leader.