By Jacob L. Shapiro

The struggle against statelessness is a struggle against other states. Even now that nationalism has become currency and credo in a global order in which the ties that bind seem as though they can’t be cut fast enough, and in which barriers seem as though they can’t be built strong enough, independence movements fare no better than when multinationalism was so in vogue.

It’s in this context that we think about the Kurds and the Catalans, two stateless nations that plan to put their respective independence to a vote. On June 8, Masoud Barzani, the president of the Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq, said the KRG would hold an independence referendum on Sept. 25. The next day, Carles Puigdemont, the president of Catalonia in northeastern Spain, said Catalonia would hold a referendum on Oct. 1.

The list of differences between these two nations, of course, is extensive. Catalonia is a part of Spain, and Spain is part of the West, where nationalism was born and nurtured for centuries. This kind of national consciousness has been around in the Middle East for a century at most. Catalonia is wealthy – wealthier than several EU nations, in fact – and the KRG is poor, dependent almost entirely on oil revenue it must share with Iraq. Catalonia is coastal; the KRG is landlocked. Catalonia is Christian; the KRG is Muslim. The list goes on.

But if you dig a little deeper, you’ll find that similarities abound. They are both part of states that were created even more arbitrarily than most. Spain is the product of marriage, famously unified when the Aragonese and the Castilians joined their houses in the 15th century, bringing with them disparate peoples and cultures that still have never really learned to live with one another. Iraq was the product of imperialism, a country in which foreign powers jammed together three large rival demographic groups – Sunni Arabs, Shiite Arabs and Kurds – without much rhyme or reason.

Both of the national governments to which the Catalans and the Kurds belong are also young. The current iteration of Spain began only after democracy was restored in 1975. (Shortly before that, the Catalans had been oppressed under the regime of Francisco Franco.) The current Iraqi government was created in 2005. (Shortly before that, Kurds had been oppressed under the regime of Saddam Hussein.)

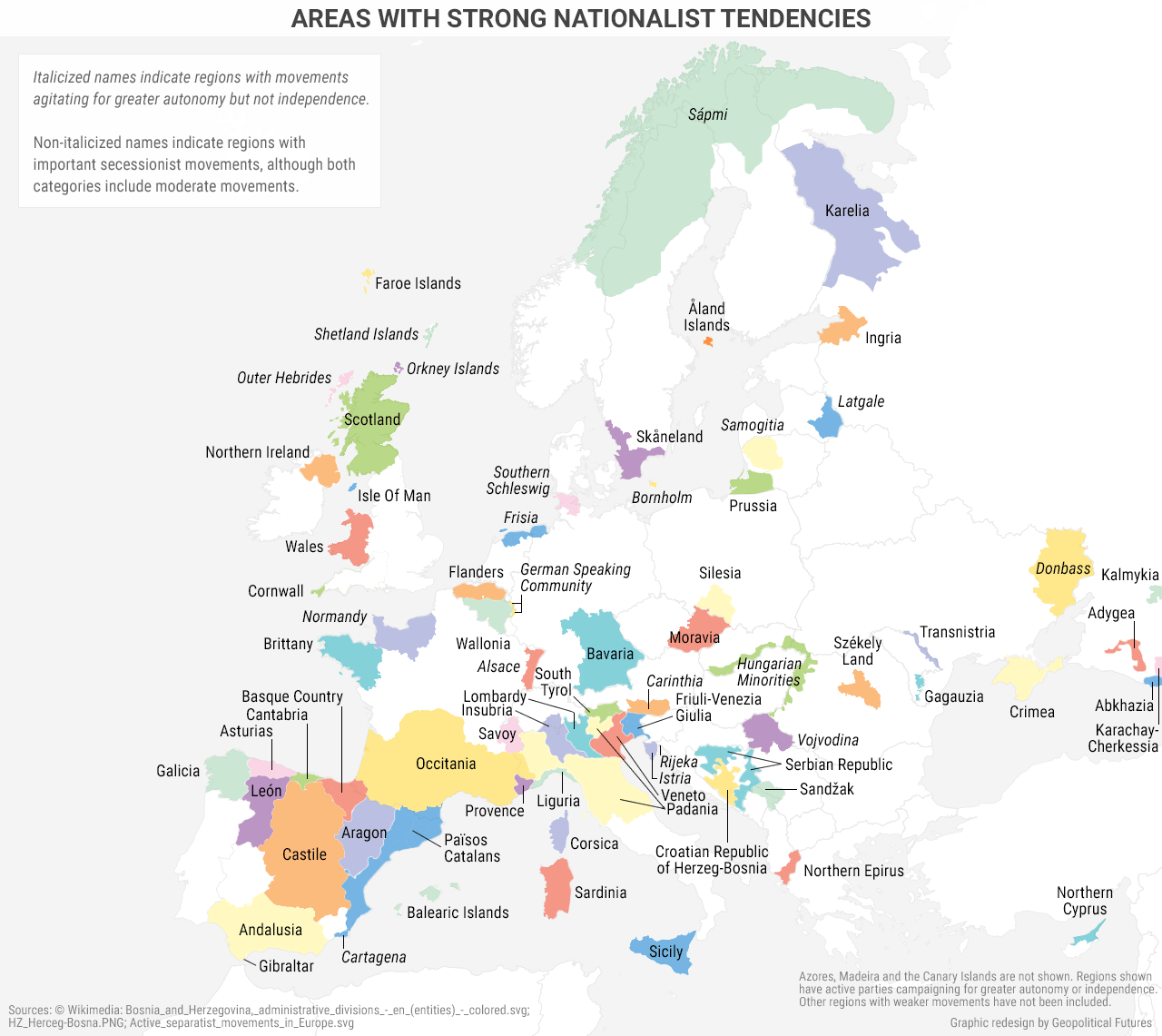

Perhaps the most striking similarity is that Catalonia and the KRG are both characters in a much longer story of nationalism. It’s a centurieslong story in which the world moves away from multinational empires to smaller states whose sole responsibility is to protect national interests. And now the Catalan and Kurdish pushes for autonomy appear to be gaining momentum. The conditions under which their respective movements are doing so may be different, as is the relative importance of each movement, but the movements themselves will necessarily shape the future of their regions and indeed the world.

The Story of Nationalism

Nationalism may have begun as a European ideology, but it is now undeniably global. In some regions, it’s a newfound phenomenon; in others, it’s a renaissance. It’s a concept that dates back centuries, but it adopted new meanings after the end of World War II. The new world order brought promises of self-determination that were never fully honored, partly because the Cold War turned stateless nations into proxy groups in the battle for global hegemony. Now that the Cold War is over, these nations see that if they have no strategic value to a great power, the best way to defend their interests is to have a country of their own.

Attendees hold posters reading “Because I’m democrat” and “Because it’s my right” during a political rally supporting a referendum on independence, at the Congress Palace of Catalonia in Barcelona on May 19, 2017. JOSEP LAGO/AFP/Getty Images

But countries are not given freely. National independence is something that is won, not granted. This is why there are so many armed groups fighting for autonomy throughout the world. Revolutions are not something that groups ask permission to undertake. Revolutions are revolutions precisely because they upend the status quo.

Even in the rare instances in which statehood was “given,” independence was not guaranteed. Take Israel, for example. The United Nations may have approved the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine in 1947, but there would be no Israel if so many European Jews had not migrated to Israel and fought for its independence. Nor would Israel have become a state if it had put the decision on independence to a committee and a national referendum.

Most modern countries, in fact, fought for their freedom in some form or fashion. And their “success” reveals one of the great inconsistencies in democratic thought: the inability to tolerate secession. If a country is set up on principles of freedom and national self-determination, it is logically inconsistent to deny that self-determination to a component of that country that desires its own independence. But it happens anyway, because politics is based on interests and not ideological consistency. Often this sort of inconsistency leads to civil wars – and even after the civil wars, this inconsistency never goes away. The United States, for example, fought a bloody civil war, and there are still cultural and political divides between north and south. Much more recently, the United Kingdom dealt with Northern Irish separatism during the time of the Troubles, and though the fighting ended, the issue isn’t entirely resolved. (Scotland, meanwhile, continues to hold referendums on independence.) Catalonia has been part of Spain for hundreds of years, and yet the latest polls indicate that 44.3 percent of people in Catalonia would vote for independence if the referendum were today. Nationalism, in other words, is resilient.

The Only Difference That Matters

At some point in their respective histories, the Catalans and the Kurds have fought for their independence, just as so many other stateless nations have. But there’s an important difference between the two independence referendums – and it’s the only difference that matters: There are no Catalan militias arming for war. Catalonia has a strong cultural identity, but it also has a strong economic interest to remain a part of Spain. But there is no single thing Catalonia wants besides being treated better by Madrid. Are Catalans willing to die for Catalonia, and are Spanish soldiers willing to kill for Spain? The answer right now is no, so for the time being, Catalonia is willing to vote for independence while the KRG is willing to die for it.

In the KRG, however, the Kurds’ armed forces, the peshmerga, have been fighting the Islamic State for some time – and claiming territory in the process. The government in Irbil doesn’t trust the Sunni Arabs of Iraq, who have wronged them so many times in the past, any more than it trusts the Shiite Arabs, with whom they have recently vied for strategic territory. For the Kurds, it’s not only an issue of cultural identity or economy but of survival, surrounded as they are on all sides by hostile forces. Having learned that security promises by outsiders like the United States are hollow, they are compelled to carve out space for themselves. The referendum, then, is more of a formality than a proper vote.

This explains why Turkey, Iran, Germany, the United States and countless other nations are so much more concerned with Kurdish independence than Catalan independence. Were Catalonia to leave Spain, it would be another instance of devolution in a continent for which devolution is historically a defining trait. It would not fundamentally alter the geopolitics of Europe anymore than the rise of nationalism already is. Were Kurdistan to become a country – one that gained foreign recognition and could unite Kurds of other countries under its banner – it would transform the Middle East.

That the two independence referendums were called within a day of each other may be coincidence. That it happened now, when multinationalism is increasingly seen as obsolete, is not. Whether the votes create new states will be determined by the conflicting imperatives and interests of the parties involved, not the theoretical rights to self-determination. Simply saying you want to be free, historically, has never been enough.