By Jacob L. Shapiro

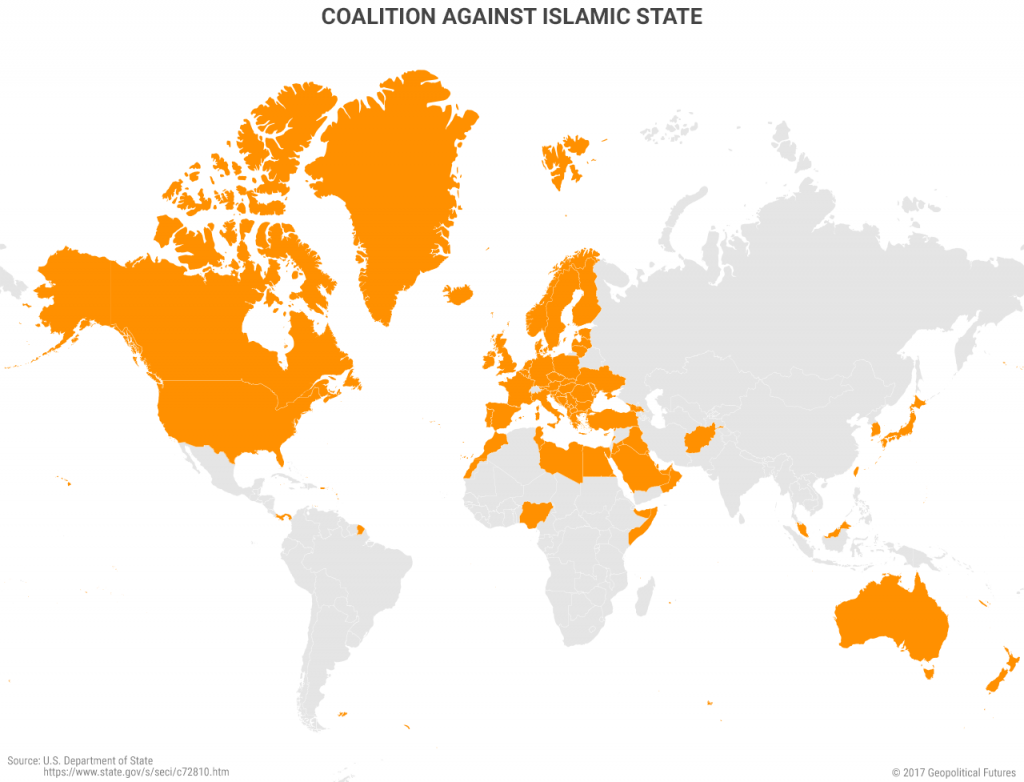

Senior officials from the 68 member countries of the Global Coalition to Counter ISIS met in Washington on Wednesday. Yesterday, the Islamic State claimed responsibility for a terrorist attack in London that occurred the same day the coalition met. According to the U.S. State Department, this coalition has been pouring significant resources into the global war against IS. Twenty-three countries have contributed over 9,000 troops. Coalition air assets have conducted over 19,000 airstrikes against the jihadist group. More than $22 billion in aid has been spent, and another $2 billion is expected to be raised in 2017. But the coalition’s existence raises an uncomfortable question: If the combined forces of 68 countries have fought IS for over two years, how does IS still exist?

Coalition-building has become a favorite tool of the United States in its long-running war in the Islamic world since 2001. When the administration of U.S. President George W. Bush attacked Iraq, it assembled a “coalition of the willing” consisting of 48 countries that supported the U.S.-led invasion, either politically or militarily. When the administration of President Barack Obama decided to intervene in Libya in 2011, it did so alongside the United Kingdom and France, with support from a NATO coalition of Jordan, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and Sweden. If the results of these previous efforts are any indication, the current existence of a grandiose coalition does not guarantee IS will be destroyed.

One problem is distinguishing between coalitions and alliances. When the U.S. invaded Iraq with its “coalition of the willing,” only four countries sent combat troops as part of the invasion force: the U.S., which sent about 130,000 soldiers, the U.K., which sent 28,000, Australia, which sent 2,000, and Poland, which sent 200. Other countries signed on. But the U.S. touted this coalition more as a public relations strategy than an alliance jointly pursuing strategic goals according to each country’s interests. When a group of countries is invested in the defense of each other, “coalition” is rarely the word used. These are alliances, which commit the involved states to defending the other states’ interests as they would their own. This currently is the main problem the U.S. has with NATO: It behaves more like a coalition than an alliance.

Looking at the 68 member countries signed up to fight IS demonstrates just how ineffective this coalition will be. First, the countries involved have radically different interests. Afghanistan is a broken state with a significant IS cell within its borders. Saudi Arabia sponsors groups not too ideologically dissimilar from IS to advance the Saudis’ strategic interests in Syria and Iraq. Saudi Arabia’s main complaint with IS is not that it exists, but that it became too powerful too fast – meaning IS could potentially threaten the kingdom’s interests. These coalition countries are supposed to share common interests with countries like Taiwan and Iceland, which aren’t particularly affected by developments in the Middle East.

The countries not asked to participate in the anti-IS coalition are also telling. Syria – or what is left of it – arguably has more reasons to fight IS than any of the others, considering that IS has swallowed a significant chunk of Syrian territory. Iran views IS as an existential threat. If IS consolidates control of a large territory in the Sunni Arab world, the Shiite-dominated regime in Iraq would be in mortal danger. That would challenge Iran’s position in the region. Russia is also not on the coalition list, although it is one of the most active countries in terms of attacking IS-held positions on the ground in Syria.

The U.S. does not see eye-to-eye with the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, with Iran, or more broadly with Russia. But each of these powers shares one thing in common: They all see IS’ destruction as advancing their interests. Aid from states like Russia or Iran would be far more beneficial in a global coalition against IS than smaller countries like Montenegro or Luxembourg. Russia and Iran have more resources and view IS as a more serious threat that they would be willing to spend resources on. A smaller country in the middle of Europe has little reason to commit troops. These smaller countries may be able to share intelligence or block certain IS financial activities, but they can’t address the root problem – IS’ capable military forces in the Syrian and Iraqi deserts.

British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, center, speaks with French Foreign Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault at the U.S. State Department during an afternoon working session with leaders from a global coalition to defeat the Islamic State, on March 22, 2017 in Washington, D.C. Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images

This coalition exists not to destroy IS, but to express disapproval of it. Coalition members hope to reap political benefits from saying they do not support IS. It is an easy calculation for most of these nations. The U.S. wants to show it is leading a global effort against IS, and any country that signs on knows the U.S. will appreciate the gesture. Gaining the appreciation of the world’s most powerful country at the low cost of declaring IS reprehensible is a good deal. The U.S., meanwhile, wants to claim it is not becoming lost in another misguided venture in the Middle East while disproportionately assuming the costs. Appearance is more important than reality.

For most of the world, the Islamic State is an easy target for disapproval. It has a radical political ideology, it relishes in grisly public executions, and its idea of a campfire is blowing up ancient antiquities while dancing around the relics of the infidels. Building a coalition against it that requires nothing but disapproval is akin to assembling a coalition that likes ice cream. The deeper question is what 127 other countries think about IS. Is it implied that these countries tacitly support IS? And if the coalition’s goal were as simple as destroying IS, why not partner with countries like Russia and Iran, whose interests in fighting IS are not contrived?

The answer is that coalitions are political instruments, and dull ones at that. They exist for the sake of optics, not for realizing strategic goals. To defeat IS, a large army willing to attack the group in its remaining strongholds in Syria and Iraq is needed in the short term. The anti-IS coalition says it has taken 62 percent of IS territory away from the caliphate, but the remaining 38 percent is the most important and the hardest to obtain. After that, massive amounts of money are needed, as well as a military force large enough to prevent other jihadist groups or non-state actors from taking advantage of the chaos to create new and terrible permutations to hold this land. The coalition will declare “mission accomplished” long before that happens, and with minimal sacrifice by most of its members.

Stopping Islamic terrorism is complicated and difficult, but destroying IS’ territorial base is not. If an alliance of 68 countries was committed to IS’ destruction and was willing to bear the cost, IS wouldn’t stand a chance. It certainly wouldn’t be able to force the coalition to take 15 times longer (and counting) to defeat IS in just one city (Mosul) than it took IS to capture the city in the first place. Fighting comes down to resources and will. The forces that say they stand against IS far outnumber anything IS can feasibly resist. The problem is that IS has the advantage of will. And as long as that remains true, it is the coalition that doesn’t stand a chance.