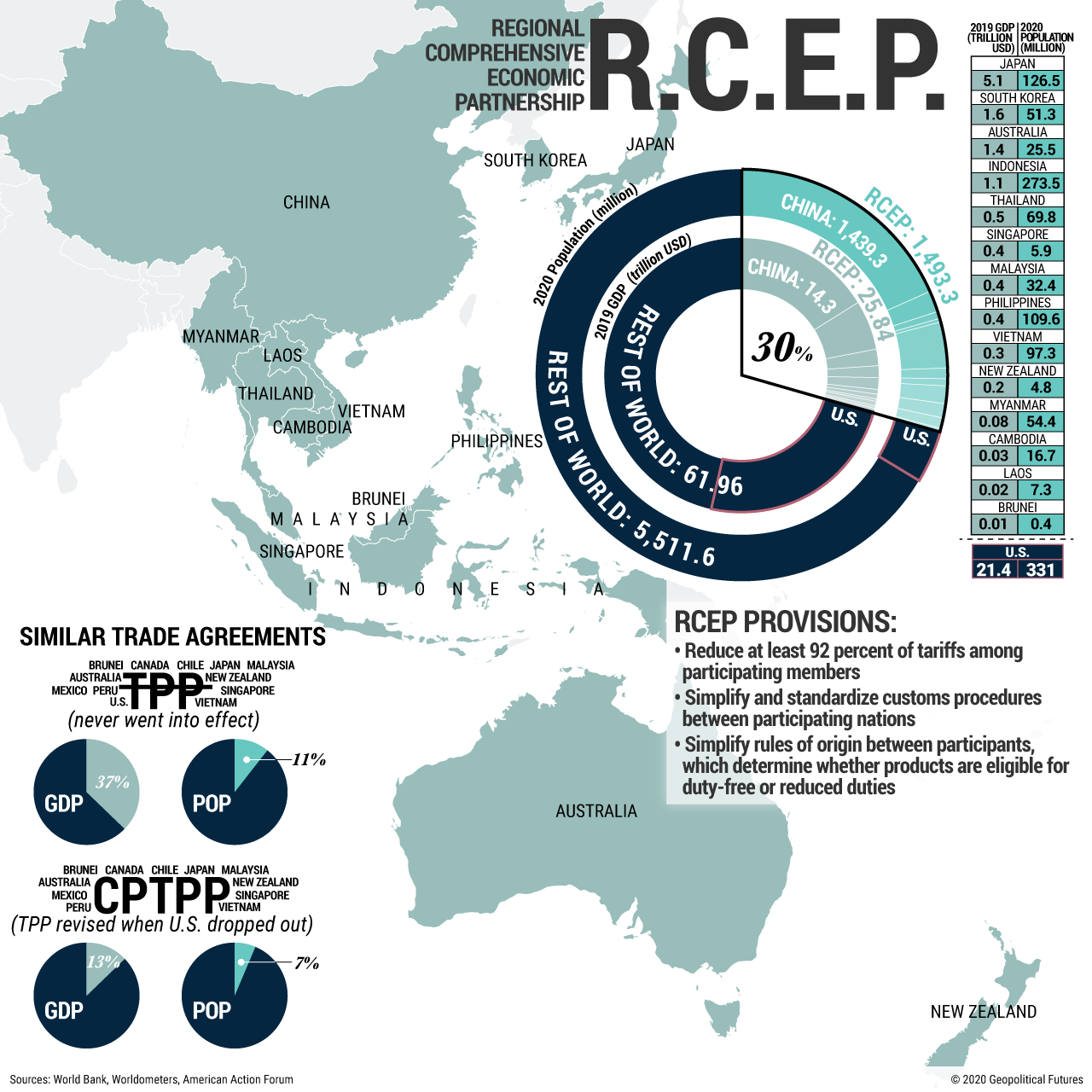

Judging solely by its headline figures, the newly inked 15-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – by most metrics the world’s largest trade pact short of the World Trade Organization – is impressive in its size and scope. Its members account for around 29 percent of global economic output, similar levels of global trade value and nearly a third of global investment. If implemented, it will dramatically reduce tariffs on a wide range of goods and make some headway on untangling a morass of regulatory complications currently impeding trade. And reaching agreement on the pact is indeed no small feat, considering the extreme range of differences in the economies involved, along with deep strategic and economic concerns held by many members about China’s inclusion.

This is why you’re seeing a lot of headlines about how RCEP is a “China-led alternative” to the higher-standard Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) – and something that highlights waning U.S. influence over the trade-obsessed region to Beijing. To be sure, America’s withdrawal from the TPP in 2017 disappointed regional allies like Japan, Australia and Singapore and deepened suspicion about U.S. interest in the region. U.S. trade moves targeting allies or potential strategic partners like Thailand and Vietnam had a similar effect. But RCEP itself isn’t particularly emblematic of a shifting balance of power in East Asia. This is, in part, because the details of the agreement don’t quite live up to its billing. Its main effect will be in harmonizing a number of existing trade agreements among its member states; it doesn’t really attempt to write the rules for trade in services, intellectual property or investment – aspects of regional economies that will matter more and more going forward. There are also serious doubts about how much of it will actually be implemented, as it leaves ample room for countries to continue imposing non-tariff barriers on trade. And, ultimately, the opportunity for the U.S. to reengage with regional trade will remain wide open; the CPTPP (the TPP’s successor) was designed to make it as easy as possible for the U.S. to rejoin if and when domestic politics make it feasible.