By Jacob L. Shapiro

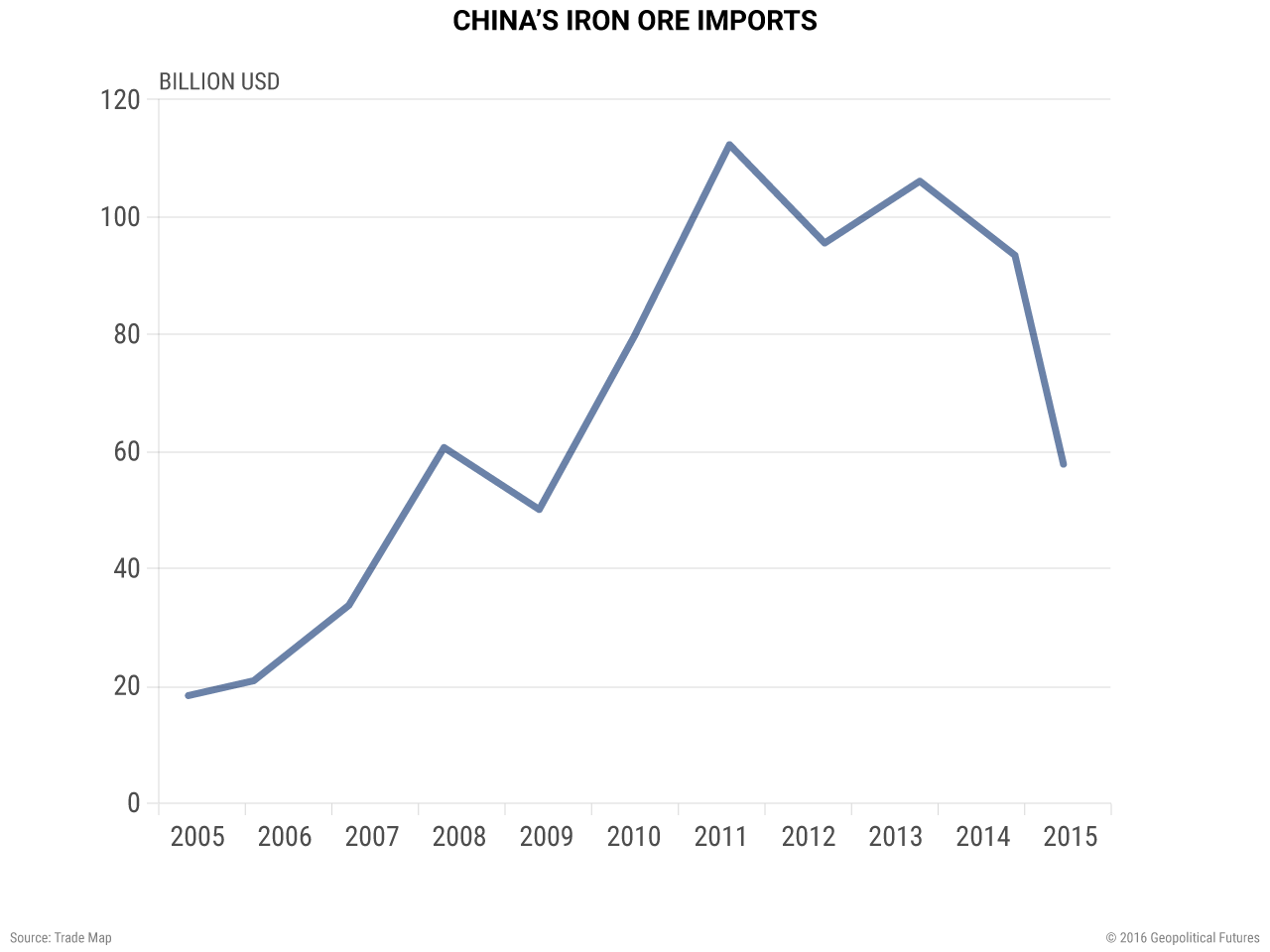

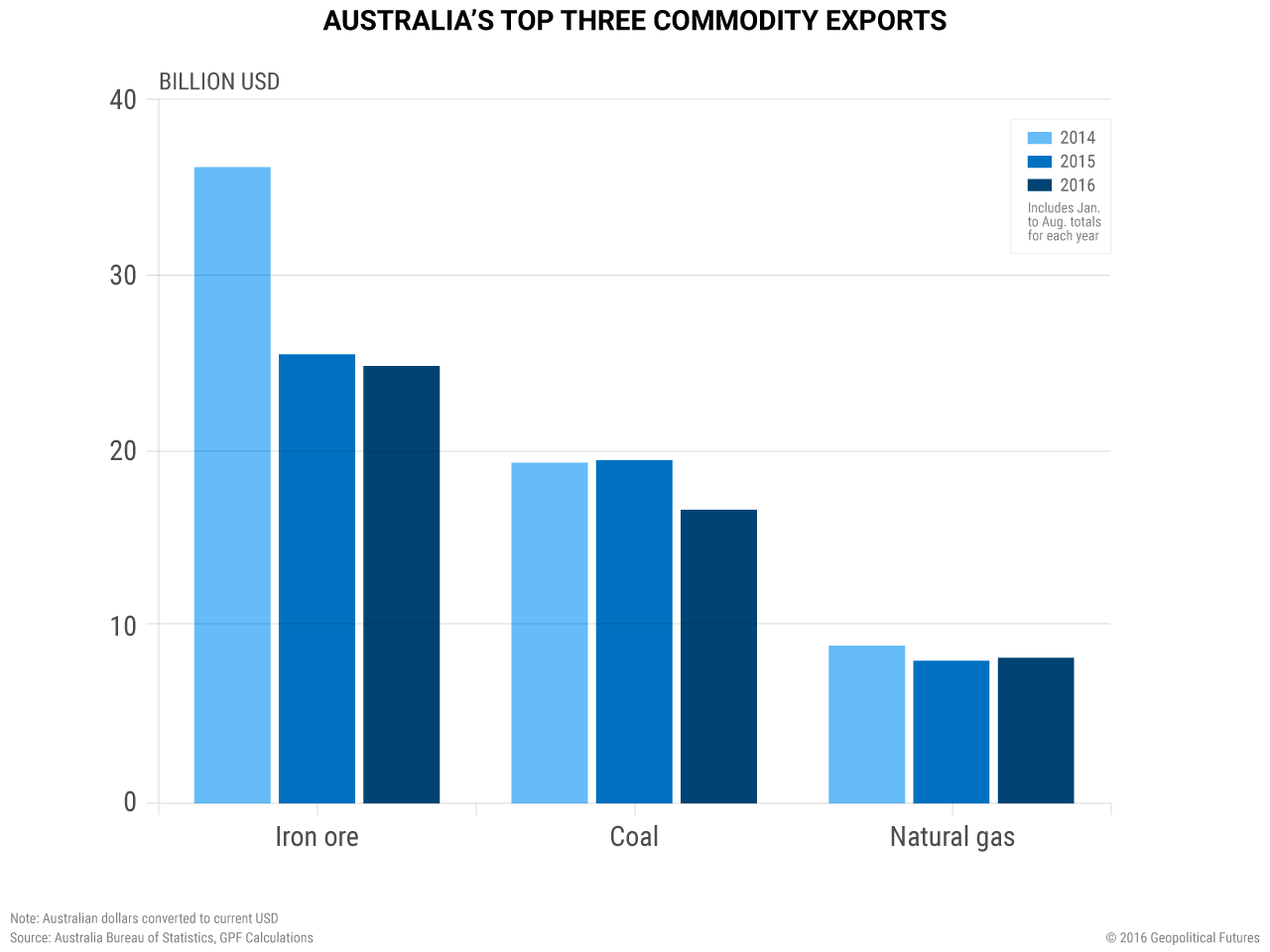

In January, we published a list of the top 10 countries affected by the global exporters’ crisis. Number five on that list was Australia. Compared to some of the other countries on our list, Australia’s exports as a percent of GDP were fairly low in 2015, just under 20 percent, according to the World Bank. But Australia was (and is) highly dependent on the export of a few commodities, like iron ore (almost 20 percent of all exports in 2015) and coal (almost 15 percent). The prices of both of those commodities in particular were facing severe downward pressure, largely due to decreased demand from China. We concluded that Australia was in for a very difficult year economically.

Australia has fared better than we expected. Moody’s issued a report this month that said Australia was the fastest growing AAA commodity exporter this year and forecast GDP growth between 2.5 percent and 3 percent in the next two years. A Reuters report published a few days later predicted similar GDP growth numbers and indicated that surging export volumes and low interest rates have underpinned strong growth. Reuters admitted that Australia’s GDP in the first half of 2016 was 1.6 percent lower due to the exporters’ crisis, but concluded that this meant the worst was over.

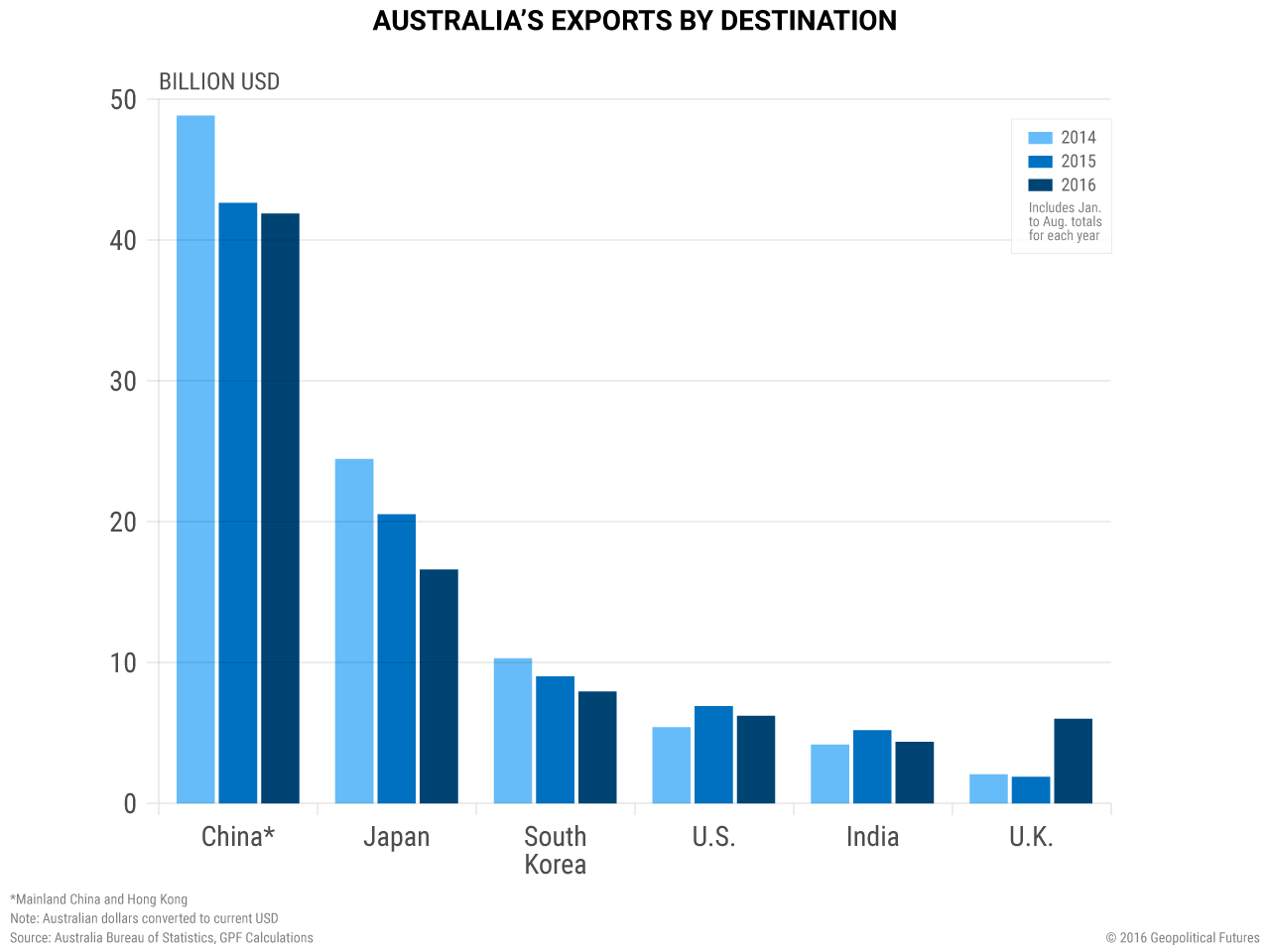

Unfortunately, this optimism strikes us as premature. Before we can explain why, we must explain why Australia has been more resilient despite the exporters’ crisis than some of the other countries on our list. Two key developments stand out when we look at the numbers. The first is that the demand for Australian exports that has offset some of Australia’s losses came from an unexpected place: the United Kingdom. The latest Australian trade statistics are current as of August 2016. If you compare the same time period last year to this year, Australia has increased exports to the United Kingdom by roughly 217 percent.

The chart above shows Australia’s top six export destinations between January and August in 2016. All but the U.K. were also the top destinations for the previous two years. Demand from Australia’s top three export destinations – China, Japan and South Korea –has dropped and is sloping downward generally. Meanwhile, demand from the United States is holding fairly steady, and demand from the U.K. is much greater than in years past. In 2015, the U.K. was the 11th largest destination for Australian products. So far in 2016, the U.K. is the fifth largest, just barely below the United States, which it may leapfrog by year’s end.

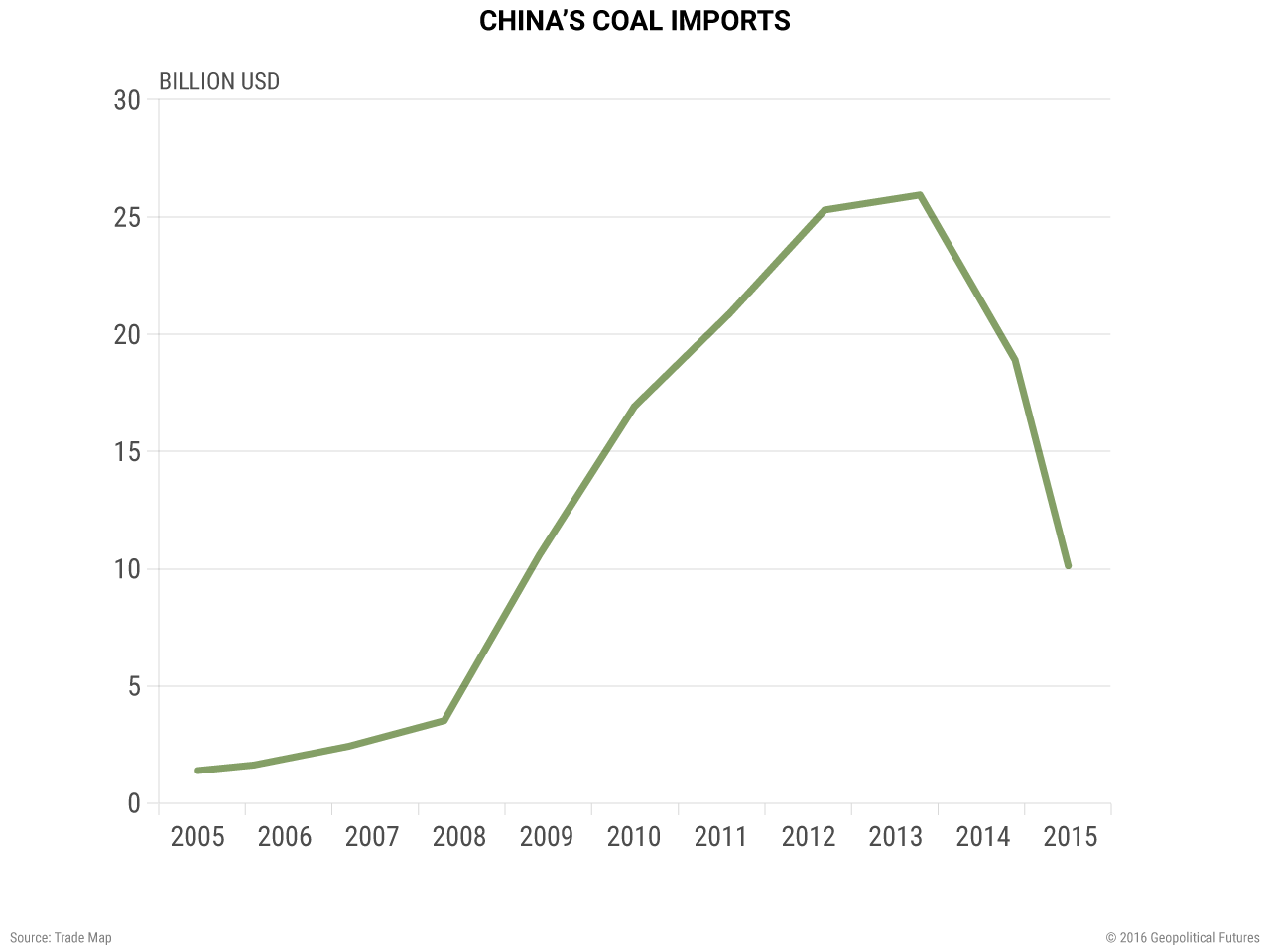

The second positive development is that there has been a rally in coal prices, specifically in thermal coal prices, which reached their highest levels since May 2014 in September at $78.11 per metric ton. This spike in prices has been led by a surge in demand from China. As the chart below shows, however, China’s coal imports have been declining for a while. China’s imports began to creep up in May and June, by 7.5 percent and 13.1 percent respectively, and that is what led to the rally in prices for Australian thermal coal, but it is an anomaly, not a trend.

The reason for the increase in Chinese demand is that the Chinese government has made curbing overcapacity in the domestic coal sector a top priority this year. In February, the Chinese State Council outlined plans to cut production by 500 million metric tons in the next three to five years and to consolidate production. China’s National Energy Administration said in the same month that 1,000 coal mines would be shut down in China in 2016 alone. The goal is to solve the oversupply issue by 2020. China’s policies created Chinese demand for thermal coal, which is responsible for sending prices upwards. This is good news in the short term because it props up one of Australia’s most important exports – but the trend line is still down overall.

The picture for some of Australia’s other most important exports, like iron ore and natural gas, remains bleak. The value of Australia’s iron ore exports so far this year when compared to the same time in 2014 has dropped 31 percent. Meanwhile, the value of natural gas exports over the same time is holding steady, but this is misleading because it isn’t a result of increased demand for Australian natural gas. According to Platts, which tracks energy markets, the average monthly price of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in May 2016 dipped to its lowest point in over six years. Australia has invested $172 billion in its LNG industry in recent years, and its LNG output will increase by 28 percent in 2016-2017 – and yet the value of its LNG exports compared to 2015 has only increased 2 percent. Australia’s three most important exports will remain under pressure in the next few years, and another spike in Chinese demand for thermal coal is unlikely, certainly not one as big as this year’s.

Australia has proved resilient despite the global exporters’ crisis, but it has not developed immunity to it. Much like Germany, increased demand from places like the United Kingdom and the United States has cushioned the blow. But Australia cannot depend on this kind of growth every year. Furthermore, Chinese demand for Australian exports will likely get worse in the short term. In 2015, China was still by far Australia’s most important trading partner, accounting for almost 30 percent of Australian exports.

In 2016, it became clear to the world that the Chinese growth miracle has run its course. As China attempts a fundamental shift in its economy, it will import fewer Australian exports and the Australian economy will face additional pressure. When you combine this with some other worrying indicators, such as the International Monetary Fund noting that Australia and two other countries are accumulating private debt at a fast rate, it is clear that Australia is far from out of the woods when it comes to the global exporters’ crisis.