By George Friedman

Yesterday was the 43rd anniversary of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. It was the war that created the modern geopolitical configuration of Israel’s borders and it is worth stopping to consider it. Its outcome led to the Camp David Accords, which ended the state of war between Israel and Egypt, and it cemented the regime of Hafez al-Assad in Syria.

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat conceived of the war for three reasons. First, Israel’s defeat of Egypt in 1967 cost it the Sinai Peninsula and created a sense of hopelessness and cynicism among the Egyptian people that threatened the stability of the regime. Second, in the six years since 1967, the Soviets kept a crippled Egypt dependent on them and demonstrated that they were incapable of helping Egypt defeat the Israelis. Third, Sadat realized not only that the simmering hostilities with Israel were pointless, but that only the United States could facilitate a respectable conclusion to a conflict.

Sadat also knew there could be no negotiation with Israel unless Israel was shocked out of its sense of omnipotence. To do this, Egypt did not have to win a war. But it had to force Israel to look into the abyss, by creating a stunningly unexpected circumstance that would at least appear to be catastrophic. What Egypt needed to do was stun Israel with an attack over the Suez Canal, which would both surprise Israel and appear to threaten its fundamental security.

From the beginning, Sadat knew Egypt could not destroy Israel. Egypt could frighten Israel, but to frighten it Sadat needed the cooperation of the Syrians. This was dictated by geography. Crossing the canal would not threaten Israel proper. But if Syria launched a surprise attack on the Golan Heights, it could very quickly threaten northern Israel. A defeat on the Golan would leave the north undefended long enough to frighten the Israelis with direct occupation of part of Israel by an Arab army. Bringing Syria in raised security issues, since Assad played many hands in every game. Without a Syrian attack, there would be alarm, but not the panic Sadat sought.

Sadat did not trust the Soviets and ordered them to leave prior to the attack. Egypt deployed a force of hundreds of thousands on the western side of the Suez Canal, and Israeli intelligence completely misread what was happening. The Israelis operated under the impression that Egypt would never attack until it could neutralize Israeli air superiority. What they failed to see was that Soviet surface-to-air missiles had neutralized Israeli air security. As with all intelligence organizations, information has no value unless it is properly analyzed. Israel had superb collectors and amateur analysts.

Sadat attacked on Yom Kippur, a day many Israelis were in synagogue. The Israelis had not mobilized during the buildup, prior to the attack. Peacetime forces manned the Suez line and the Golan. The attack started in the afternoon on both fronts. The initial attacks were brilliantly executed. Egypt crossed the canal and seized the fortifications on the east bank. The Syrians deployed multiple armored divisions to attack a handful of defenders. As night fell, Sadat succeeded in panicking the Israelis. Israel went into emergency mobilization. Rumors were flying. While the Egyptians consolidated their position on the east bank of the Suez, the Syrian armor moved toward the escarpment of the Golan. There were only a handful of Israeli defenders to stop them, and if they failed the Galilee was wide open. The Israelis looked into the abyss that Sadat built for them that night.

That handful of Israelis stopped the Syrians. More precisely, an army trained by Soviet doctrine stopped itself. Soviets planned battles meticulously and local initiative disrupted plans. For a battle against an inferior enemy, toward the end of World War II, this planning was rational. Against a well-trained and motivated enemy like the Israelis, excessive planning was suicide. Even though junior officers realized that resistance was light and that a rush, however disorderly, could overwhelm or bypass them and allow the Syrians to pass into the Jordan Valley below, senior command refused to change the plan. The slow methodical advance continued slowly and methodically, crippling itself and allowing it to be stopped by a handful of troops. By the morning, there were reinforcements on the Israeli side and the threat was halted.

It was at this point that the Americans got involved. They wanted the Soviets out of Egypt. They did not want Sadat overthrown because the Soviets might be invited back. The Americans did not want the naval base in Alexandria in Soviet hands. So, they needed to protect Sadat. Sadat was not doing badly. Another Israeli miscalculation was the utility of the AT-3 Sagger, a wire-guided anti-tank missile fired by Egyptian special forces that decimated the first Israeli armored counterattacks. But the Israeli army was simply better than the Egyptian army and in time, it would defeat it. The U.S. knew that, but it didn’t want a defeat too devastating or too quick.

The Israelis asked the U.S. for aircraft to replace those shot down, and above all, 155 mm artillery shells that they were running low on because they did not anticipate the need to go on the offensive against massed forces. They thought they would always have the initiative and that highly mobile forces were enough. The U.S. delayed sending the artillery shells. The sooner the Israelis had those shells, the sooner they would defeat the Egyptians (the Syrians were lost as soon as their plan went off the tracks). The U.S. finally started the airlift that allowed them to prevail and the tide turned in the Sinai as well.

The U.S. saw a huge opportunity. It had defeated the Soviets in a proxy war in Turkey and Greece in the 1940s. The Soviets had responded by cultivating pro-Soviet regimes in Syria, Iraq and Egypt and using the threat of Israel to cement the relationship. The Soviets did not want a settlement between Arabs and Israelis, as it would undermine their utility to these regimes. The Americans did not want Syria and Iraq to threaten Turkey from the south. Turkey blocked a sustained Soviet naval presence in the Mediterranean. Iran tied down Iraq. Israel tied down Syria. The U.S. had supplied almost no weapons to Israel prior to 1967. After France abandoned its relationship with Israel, the U.S. stepped in, not only because it wanted to threaten Syria, but because Israel was vital in maintaining U.S. control of the eastern Mediterranean.

But this moment gave the U.S. the opportunity to keep the Soviets out of Egypt, and the U.S. was not letting the chance pass. The U.S. wanted Sadat to become a hero, but it also wanted to make him reach out to the U.S. to save him. This difficult maneuver took rearming the Israelis, having the Israelis cross the border and cut off the Egyptian army and then having the U.S. intervene and conduct negotiations for an Israeli withdrawal from blocking positions west of the canal. For this, Sadat had to be willing to directly negotiate with Israel for the first time on this matter.

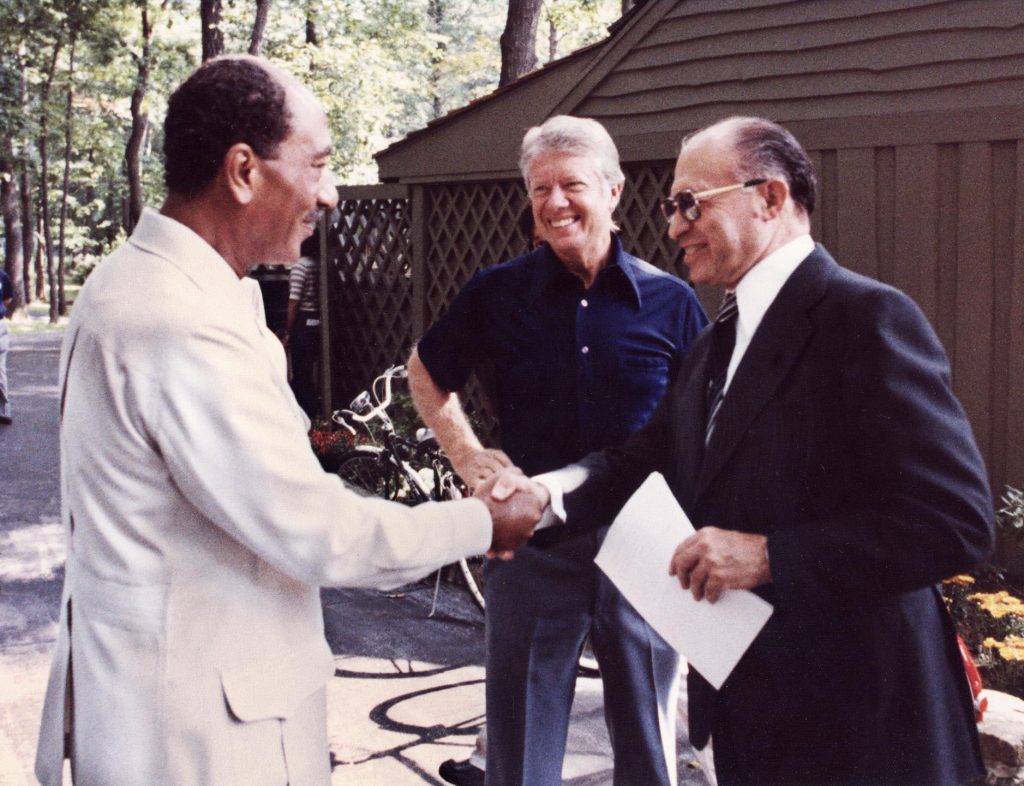

The result of the war was critical. The Soviet position in Egypt collapsed, and its only real asset on the Mediterranean was now the Assad regime, which also depended on the Soviets for its security. Egypt became an American ally and ultimately signed the Camp David Accords. As a result, Israel has not had a conventional threat against it since 1978. Jordan was quietly allied with Israel. Syria was too weak to act. Egypt, the main Arab power, ceased to be a threat. For the first times since its founding, Israel was secure from existential threats.

The war depended on an Israeli intelligence failure, and Sadat properly read Israel as blinded by its victory in 1967. That was a brilliant victory never repeated. Israel has not fought a full-scale existential war in 43 years. But it must be remembered that this was not the result of Israeli prowess, but of Egypt’s insightful read on the situation and the United States taking full advantage of the opportunity. The memory of failure and the sight of the abyss is remembered only by those Israelis older than 60. Israeli military doctrine is that it will not have to fight a conventional existential war, but only much lesser wars.

In 1973, Egypt showed how to take a weak position, and ultimately a defeat, and turn it into political victory. For Israel, the lesson should be that a strategic policy based on the assumption of omniscient intelligence and omnipotent forces is dangerous. For the United States, the lesson was that sending forces into the Middle East is a bad idea, while understanding and managing the players is a good one.

The 1973 war was very important. It taught the need for subtlety and fear. It introduced a generation of precision-guided munitions. It was a lesson for nations who depend on other nations for their weapons. It was a lesson for a generation of soldiers on both sides that survival is in the hands of history and chance, and not in theirs. This is taught by all wars and forgotten as the memory of war turns into nostalgia and recollections of terror fade into heroic works of art. This war leaves much to be considered not only in the Middle East, but to those who believe weapons are superior to subtlety in war.