By George Friedman

Our Reality Checks normally consist primarily of our reflections on global events. On the eve of the United Kingdom’s vote on whether to exit the European Union, we thought it important to focus on the actual document that will govern events should the vote be in favor of an exit. It is a relatively simple document, but containing an enormously important reality. Tomorrow’s vote can end the matter if the “remain” side wins, but simply begins the matter if the “leave” side wins.

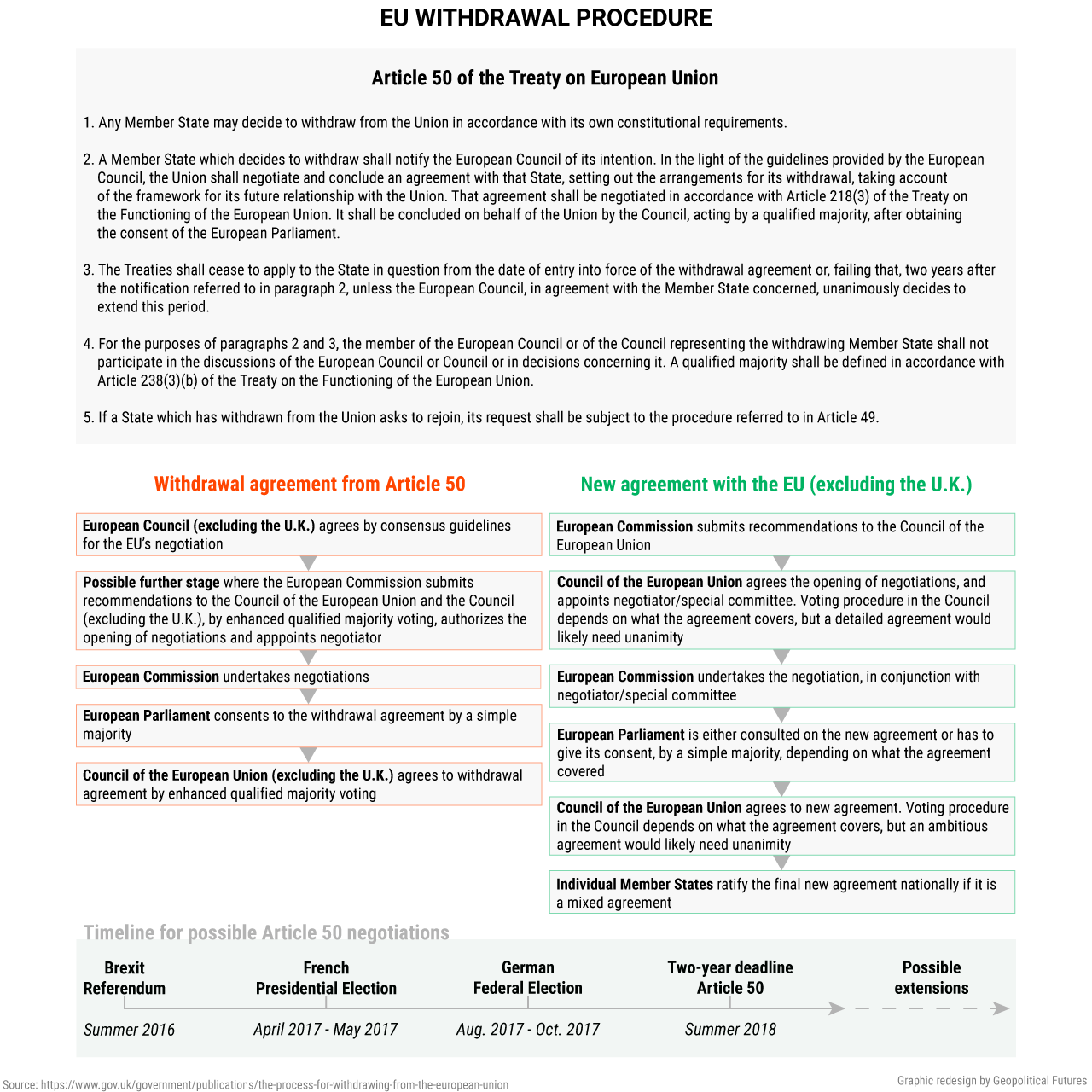

A vote to exit does not mean that the U.K. has left the EU by any means. Under the Treaty on European Union (TEU), the vote would put in motion a process that takes two years. However, the decision on whether Britain exits sooner is up to Britain. Potentially, Britain can remain in the EU even longer, if the members of the EU vote unanimously to allow it to remain longer.

The government of Prime Minister David Cameron is bound by the referendum, but is opposed to leaving the European Union. So long as he remains prime minister and maintains a majority in Parliament, it is up to him to decide what time frame he will pursue. He can leave the EU tomorrow or ask the EU to extend the time limit – in effect, the exit could be tabled indefinitely. The referendum ballot does not provide a timeline, leaving it to Parliament.

Cameron will likely have to resign if the vote is to exit, and the Conservatives will likely have to call an election. Cameron has invested so much into this that he may not be able to stay on. And the Conservatives are so divided on the EU issue that they will likely fight a vicious internal battle before going to the polls. In the meantime, the Labour Party, which is generally pro-EU, is headed by one of the most radical leaders the party has had in many years, Jeremy Corbyn.

Whether the Conservatives split and whether Labour is able to challenge the crippled Conservatives will be a vast unknown. Corbyn, if elected, will have no compunction about pushing off an exit into the distant future under the terms of the TEU. What happens if a pro-EU Conservative succeeds Cameron is another matter. I would guess the new leader would be unlikely to tamper with the referendum result, but he might push it to the two-year limit. If an anti-EU Conservative becomes leader, he might pull the trigger much faster.

The point is that according to the TEU, an exit vote settles nothing. There will be first a brutal internal fight among the Conservatives and even among Labour members, some of whom fear that Corbyn is the only man who could lose to the Tories at this point. After the dust settles on that, there will be an election and the theme of that election, if it doesn’t simply replay the whole exit question, will be how long disengagement should take. And that might result in another battle over leaving the EU after all.

If the “remain” camp wins by a tiny majority – the polls show a deadlock – then the “leave” camp will not let the matter stand. It will maneuver for another referendum down the road. That will spread the uncertainty for several years. If, on the other hand, the advocates of Brexit win by a tiny majority, they will have to deal with both the demands for a replay of the referendum, plus uncertainty over how long the exit will take. About the only way to walk away with certainty is to have a solid vote against leaving, and that doesn’t seem likely if the polls are to be believed. All other outcomes mean that Britain will remain an uncertainty for Europe.

It feels a bit like it must have felt after Abraham Lincoln’s election, waiting for South Carolina to make its move. But the adversaries in that debate were prepared to go to war to save the Union. The European Union is not something anyone would die to save. There is no Fort Sumter for the British to fire on. So this is not the beginning of war, but simply an extension of the uncertainty and squabbling that the European Union has become so well known for.