U.S. President Joe Biden’s trip to Europe has thus far pivoted around the single issue on which almost the entire world agrees: Biden is not Donald Trump. In the United States, those who voted for Trump – nearly half of all of those who voted – mourn this fact. The others cheer it. The Europeans who were present at the G-7 meeting seemed to agree that this was a wonderful thing. But most European countries are not part of the G-7, of course, and some, like Poland, dread Biden. For many European countries, the Trump-Biden issue is a non-issue. Russian President Vladimir Putin said he really thought Trump was way more interesting than Biden could ever be, but he figured Biden would be alright, if boring.

Like it or not, the trip is about the extent to which Biden will change U.S. policy in Europe and Russia, which means the trip is about Donald Trump. The way it was put many times is that the U.S. is back on the side of Europe, just as it had been since World War II. The problem with using this as a definition is that it is hard to define what it means.

After World War II, the Soviet Union emerged as a threat to a Europe that was decimated by war. It was urgent for the United States to help rebuild Europe so that it could field military forces to resist the Soviets and stabilize countries like France and Italy that had powerful communist parties. U.S. involvement had much less to do with sentimentality than a geopolitical reality that forced Western Europe and the United States into a wide-ranging alliance system. For all the talk of pious virtue, it was too soon to speak of shared values with Germany and Italy, and later, when the U.S. needed submarine bases in Spain, Washington forced itself to be polite to Francisco Franco. The U.S.-European relationship was built on necessity, not shared values.

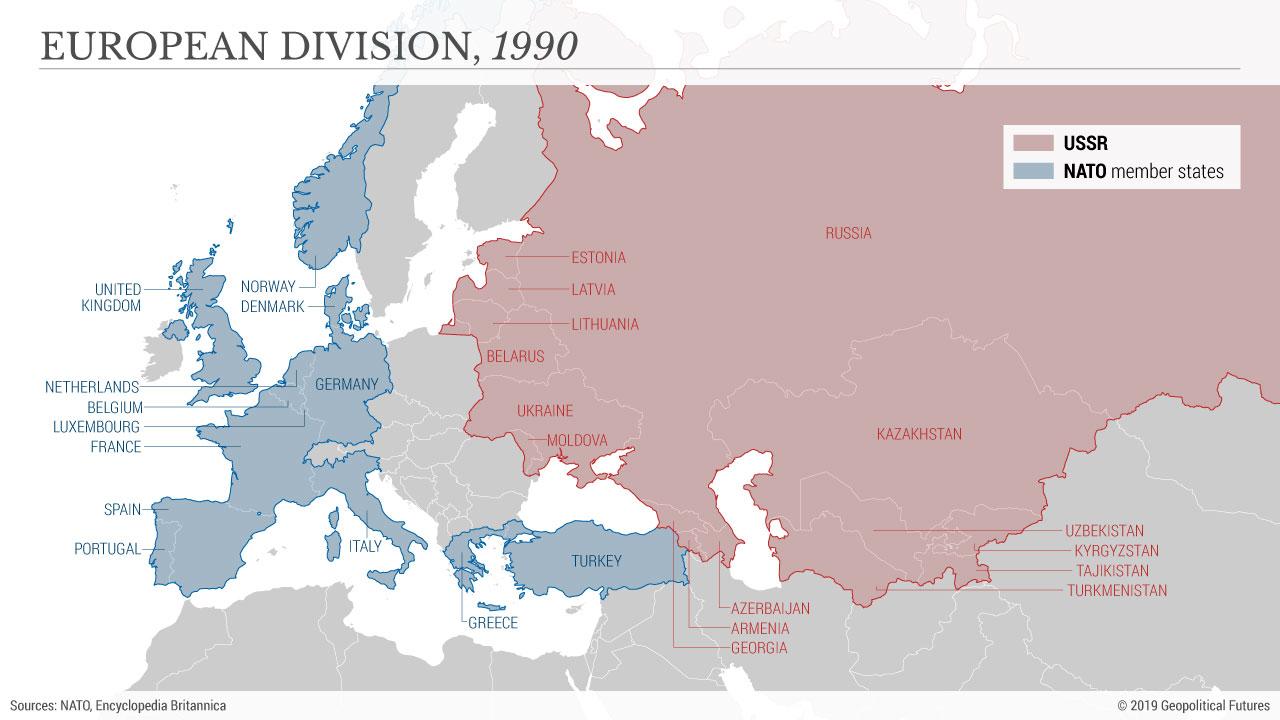

This changed in 1991. The Soviet Union collapsed, and with it the purpose of NATO. Its mission was to block or deter a Soviet attack in Western Europe. Europe and the United States created military forces suitable to the mission, and every member had a designated area of responsibility. But today, there is no Soviet Union, a fact that European countries only relatively recently discovered, dramatically decreasing their military forces accordingly. A military alliance cannot really exist without a military. So if the Russians ever advance westward, Germany, for example, would be hard-pressed to field a significant force. The U.S. would be trapped by treaty to engage and would have to carry the load. When Trump suggested withdrawing 10,000 troops from Europe, the Europeans saw it as the U.S. abandoning its commitment. Trump demanded equal efforts from other members.

The early 1990s, of course, also introduced another massive shift in the global system: the Maastricht treaty. This is important to the NATO question because one of the driving forces in creating NATO was that Europe lacked the economic ability to field an effective military force. There was no reason Europe, once recovered, could not defend itself. It was not unreasonable for Europe to want the U.S. to shoulder more security responsibility in the post-war years, nor was it irrational for the U.S. to do so; it gave it the ability to avoid war, keeping the decision out of the hands of Europeans who had been frankly irresponsible in 1914 and 1939. But the point now is that the gross domestic products of the European Union and of the North American free trade zone are roughly equal. At this point, it is hard to see what the purpose of NATO is, or what value it has to the United States. Washington’s primary focus is on China, and NATO is playing almost no part in it. It is not unreasonable for the U.S. to require European military and diplomatic participation in this competition, and there is little reason to keep significant forces in Europe.

The creation of the EU also signaled what had long been obvious: that Europe was no longer dependent on the U.S. economically. If anything, it sparked an era in which Europe pursued economic policies that challenged U.S. interests. The idea that the U.S. and EU might compete, while the U.S. remained responsible for Europe’s security, is and was bizarre. It was a great deal for Europe but hard for the U.S. to stomach.

It is difficult, then, to understand what it means for the U.S. to rejoin its European partners. The circumstances that created that partnership are gone. And given that Europeans are not particularly sentimental about the U.S., they have an interest in this relationship that diverges from the American. They want U.S. military guarantees and, to some extent, American economic cooperation, while the U.S. wants Europe to take more responsibility for its own defense.

The U.S. and Europe are, moreover, divided on fundamental issues, as are individual EU members. Take the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, for example, which carries Russian natural gas to Europe. Poland is horrified, Germany eager, Portugal indifferent. The European Union is weakening under the pressure of the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Britain has left, and the EU is threatening to throw out Poland and Hungary, while the EU tries to figure out how to care for the needs of myriad countries with one central bank.

There are geopolitical issues on which Europe must either make a commitment or deny involvement. One is Russia, which in truth is much weaker than it makes itself out to be. Even so, a country’s military power is relative to its opponents’. Right now, Europe cannot defend itself against the distant but not zero chance of Russia moving much farther west. This is especially relevant now that the United States is engaged in a confrontation with China. The Europeans must either coordinate and share risks with their ally or make it clear that they won’t.

Europe has the option of rejoining the trans-Atlantic alliance with military capabilities based on its economic power of today, not of 40 years ago. An alliance is based on shared risk, and to be sure there are risks, even if they are less existential than those of the Cold War. If Europe chooses not to act, then individual countries may. The EU is merely an economic treaty, not a nation-state, and not responsible for defense policy. But economic policy defines defense capabilities, and if the irrational structure of the EU that separates economic power from military power ever made sense before 1991, it certainly no longer does.

The U.S. has two choices if Europe does not change its direction. The first is to withdraw from Europe, leaving defense of the Continent to the Continent as it turns its attention to China. The second is to ignore the European Union and deal with individual European states on both defense and economic matters, effectively bypassing the EU. For the U.S., both strategies pose problems. The EU seems reluctant to enter into far-reaching actions against China, preferring more modest and less risky ones. Working with individual countries might not work and could entangle the U.S. in intra-European politics. The clarity of NATO’s mission in the Cold War no longer exists. On an issue central to the United States, returning to Europe carries minimal returns.

On the whole, a meaningful alliance would benefit the United States, but the question is whether the Europeans want a meaningful alliance. Going to a meeting and not insulting the hosts does not constitute a return to Europe. And given that Europe is not inclined to make the painful decisions that a modernized relationship requires, it is hard to understand what a return to Europe means, except for having dinner with some interesting people. It is 2021, and it is up to the Europeans to realize that the issue is taking a modern role if they want an alliance.