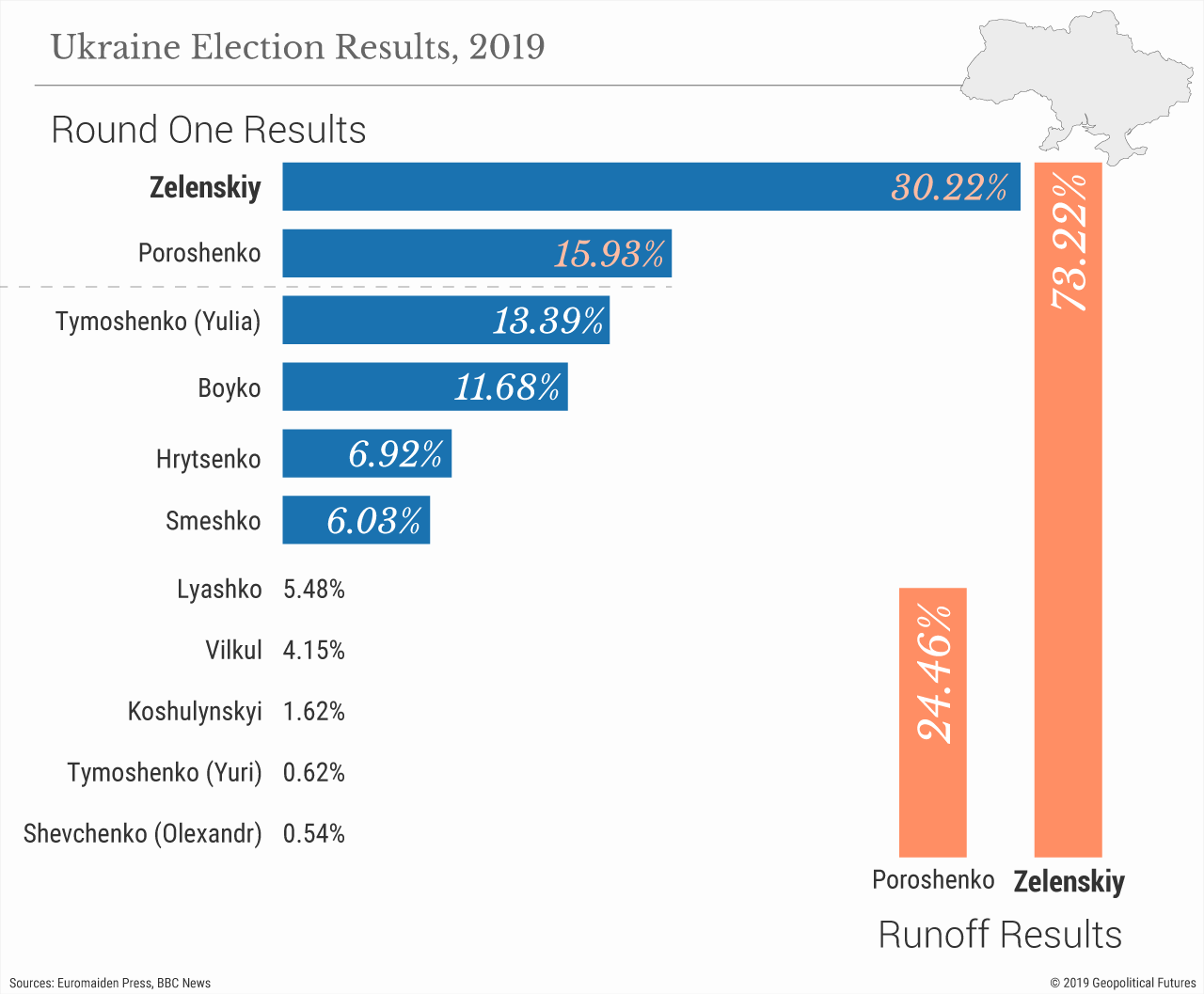

Ukraine held its second round of presidential elections on Sunday, and the results are in: The country will be led by a comedian. Volodymyr Zelenskiy earned 73 percent of the vote; incumbent Petro Poroshenko just 24 percent.

Poroshenko has already conceded, but it’s difficult to say how much he will be missed. For all the promise of the Orange Revolution and the Maidan protests that eventually led to Poroshenko’s ascension, Ukraine never really began to live, as Poroshenko put it, “in a new way.” Poroshenko himself is a member of the oligarchic class that has long dominated Ukraine, and though his administration was a material threat to many of his contemporaries, it was hardly a threat to the system itself.

The House Poroshenko Built

Although estimates of the exact magnitude of their wealth vary, Cyril Muller, the World Bank’s Europe and Central Asia chief, has said that the net worth of the three richest Ukrainian individuals exceeds 6 percent of gross domestic product. In 2018, Ukrainian magazine Novoye Vremya put the wealth of oligarchs Rinat Akhmetov, owner of one of the largest holding companies in Ukraine, around $12.2 billion, and Privat Group co-owners Ihor Kolomoyskyi and Gennadiy Bogolyubov at about $1.6 billion each. Poroshenko himself controls some 100 state-owned enterprises and comes in at the 6th richest in the country, according to the magazine, with an estimated actual wealth of $1.1 billion. The oligarchy controls sectors from the media and metallurgy to telecommunications and natural gas, and Ukraine’s richest individuals invest in the political sphere to reap personal benefit.

Poroshenko came to office with promises to curb their power. In a country with rising poverty and debt, that was a winning message. Among his initiatives was a push to nationalize key enterprises and reduce the capital held by the country’s oligarchs. His reforms were also driven by pressure from the United States and European Union, which were concerned that the oligarchic system discouraged foreign investment.

However, in practice any power Poroshenko took from the oligarchs was transferred into his own hands. Seeing the centralization of power as his only hope for holding on to that power, Poroshenko reneged on another key campaign promise: to empower Ukraine’s region governments. Poroshenko claimed his reversal was due to increasing separatism. But in truth, power transferred to the regions would likely end up in the hands of other oligarchs – and that would allow them to nominate someone other than Petro Poroshenko for president.

In centralizing power, Poroshenko bred bad blood between himself and the country’s richest, most powerful men – men like Dmytro Firtash, who controls much of Ukraine’s natural gas distribution; Vadim Novinsky, who has a major stake in Ukrainian metallurgy; and Sergei Taruta, former governor of Donetsk and founder of the Industrial Union of Donbass, one of Ukraine’s largest corporations. Most powerful among Poroshenko’s foes, however, is Ihor Kolomoyskyi, who, during the collapse of the Soviet Union, established PrivatBank, now the largest commercial bank in Ukraine. Kolomoyskyi, the former governor of Dnipropetrovsk, had a major falling out with Poroshenko when the president dismissed him from his office in 2015 and, the following year, nationalized PrivatBank – with serious implications for Kolomoyskiy’s fortune.

Many of the country’s oligarchs have a vested interest in a stronger parliament and a weaker presidency – a system on which their wealth depends. Fortunately for them, they are able to exercise enormous influence over elections by funding their preferred candidates’ campaigns and heavily influencing the media. (Ukraine’s key media outlets are largely controlled by oligarchs.), Kolomoyskyi, along with many of his peers, feared another Poroshenko term could mean the complete destruction of his business empire, and they lined up to support his various opponents in the race.

President-elect Zelenskiy is often portrayed as a man of the people. And while he, unlike Poroshenko, is not an oligarch, he has the oligarchs’ backing and so is unlikely to go up against them. And judging by the election results, it seems that despite Poroshenko’s best efforts, the oligarchs remain extremely powerful, and their power is unlikely diminish under the Zelenskiy administration. Still, it’s difficult to say what exactly Zelenskiy’s election will mean for the oligarchy’s future. Zelenskiy said in an interview that he would dissolve the Rada, Ukraine’s parliament, as soon as possible; it’s packed with his opponents, and he knows he’ll have trouble getting his agenda through the current assembly. But there are Rada elections comping up later this year, during which each oligarch – Poroshenko included – will do their best to promote candidates who will advance their interests. And Zelenskiy, for his part, cannot just dismiss the oligarchs. He’ll have to negotiate with them if he wants to hold onto power. Don’t expect him to take any tough political action in his first term.

Meanwhile, in Moscow

Perhaps nobody is paying more attention to Ukraine’s political uncertainty than Russia. Turmoil there worries Moscow far more than a Ukrainian ship in the Sea of Azov. Perhaps the worst-possible scenario – the outbreak of a political struggle between oligarchs and collapse of an already fragile Ukraine – would cost Russia dearly; Russian firms and businesspeople have invested heavily in Ukrainian sectors like telecommunications and energy.

Ukraine also remains an important buffer zone for Russia. It’s a key transit zone for Russian oil and gas exports to Europe, and despite ongoing talks, there’s no quick or easy alternative route for those exports to Europe. Neither Russia nor Europe is interested in letting the simmering Ukraine conflict become a serious confrontation between Russia and the West.

Zelenskiy has shown somewhat less hostility toward Russia than his predecessor, and a slight warming in bilateral relations can be expected – but no more. Ukraine’s foreign policy remains unchanged, and for the moment Zelenskiy will have to focus on managing internal changes. And this fall, he’ll have to watch the new elections, when Ukraine’s businessmen continue trying to recoup their losses.