In “The Next 100 Years,” I described Turkey as an emerging regional power that would over time extend its sphere of influence to resemble the range of the Ottoman Empire. Over the past decade, in spite of pressure from various directions, it has refrained from taking risks to assert itself. This changed significantly in recent weeks, signaling what is, in my opinion, the inevitable emergence of Turkish power.

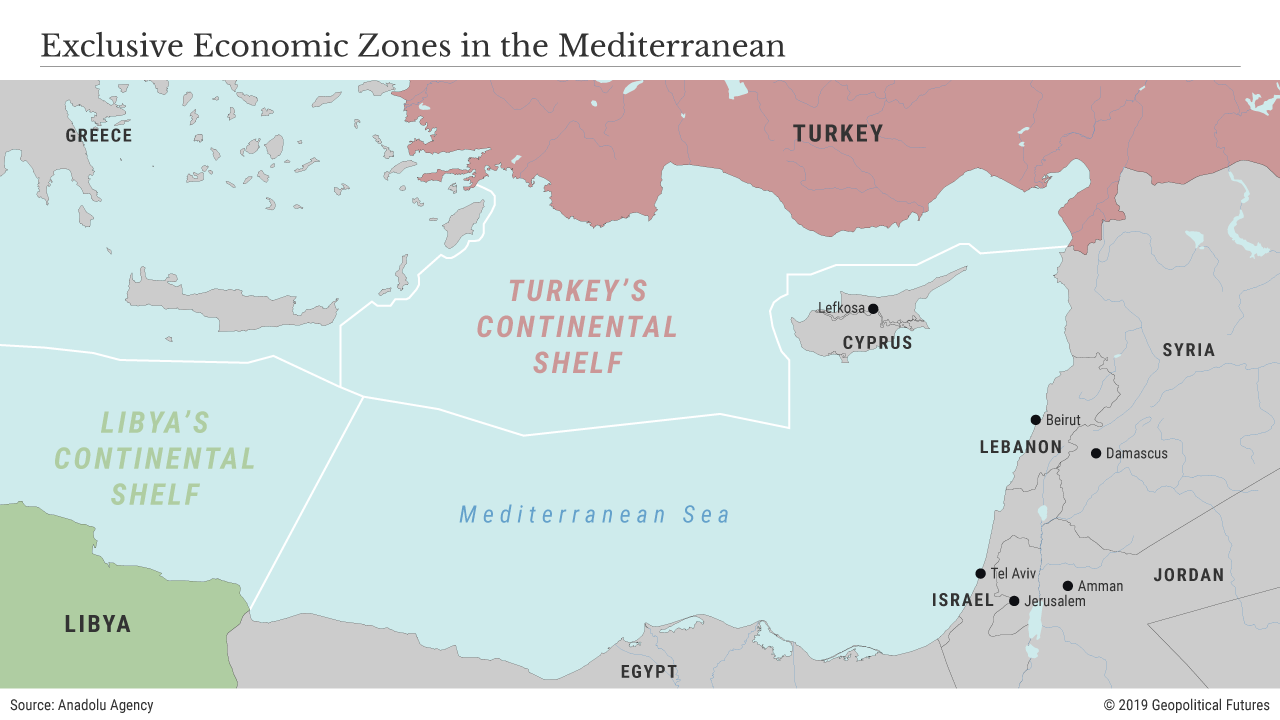

The shift came in two steps. First, Turkey announced that it had expanded its exclusive economic zone in the Eastern Mediterranean in collaboration with Libya’s Government of National Accord. Second, Turkey announced that it was building six new submarines. The construction of new submarines is not of immediate significance, nor is Turkey’s relationship with Libya, whose cooperation it needed to extend its EEZ. But together, these moves indicate a change in Turkish posture.

A Significant Gesture

Notionally, the agreement with Libya creates an economic zone that divides the Mediterranean to the east and challenges Greek Cypriot influence. At first glance, this appeared to be simply a gesture, even if a significant one. An economic zone does not define military spheres of influence. It simply denotes an area of economic domination, and Libya’s agreement to reconfigure Turkey’s EEZ, in the midst of an ongoing civil war, doesn’t mean much. Turkey’s move was perplexing but not necessarily significant.

Turkey’s announcement a few weeks later that it would send troops to Libya to defend the GNA against insurgents led by Khalifa Haftar increased the significance of the EEZ changes by several degrees. A shift in Turkish policy was visible to us when Ankara demanded that the U.S. withdraw its forces from an area of northern Syria that housed Kurdish troops. Thus far, Turkey had been cautious with incursions into neighboring countries. This time, however, the Turks intended to send a large number of forces, likely for an extended period, extending Turkey’s unofficial border into Ottoman-era territories. It was an interesting move but not a definitive one.

The decision to send Turkish troops to Libya represents a dramatic extension of this policy. In the past, Turkey had sent troops into Cyprus to counter what Turkey saw as Greek Cypriot threats against Turks. But the move into Libya is a major shift. One of the motives is undoubtedly oil. There is a global glut in oil and prices remain moderate, but that can change, and even in a global glut, access to oil can be shaped by politics. Turkey depends on oil from various regional sources, including Russia. That is a precarious position for Turkey as it cannot be a regional power without access to energy. It has been looking, along with others, at deep sea drilling around Cyprus. But Turkey’s quest for Eastern Mediterranean oil and gas has been difficult, fiendishly expensive and unsuccessful. Libya has developed oil fields, and, if pacified, could support Turkish needs and reduce its vulnerability to other sources. Interestingly, the Turks are recruiting pro-Turkey forces in Syria to join their efforts in Libya.

Of great importance is the fact that Russia supports Haftar through economic support, military equipment and Russian mercenaries. The U.N.-backed GNA has been on the defensive for an extended period, with a great deal of international support in the shape of strong statements, but not enough force to break Haftar. The Russian support would appear to be decisive.

In addition to wanting to secure sources of energy, Turkey wants to make it clear that the Eastern Mediterranean is a region where Turkish interests have to be considered. This places it at odds with almost every power in the region. For Moscow, the planned Turkish intervention in Libya runs counter to long-standing Russian interests. Although, it’s possible that Turkey and Russia have made a deal for the joint administration of Libya. Turkish claims in the Eastern Mediterranean also run counter to Israeli drilling projects off the coast of Cyprus. Israel has protested vigorously, in concert with Greece. Egypt, a backer of Haftar’s Libyan National Army, is also hostile to the Turkish move and has good relations with Israel and Greece and interests in protecting its resource-rich continental shelf. Thus, it appears that two blocs are emerging in the Mediterranean: Turkey and the Libyan GNA on one side, and Israel, Cyprus, Egypt, Greece and the Libyan LNA on the other.

An important question is what the Europeans will do. Italy has substantial interests in Libya focused on oil and is part of the EastMed gas pipeline, along with Israel, Cyprus and Greece. Greece, while attracted to Turkish support of the central government, is a member of the European Union, hostile to the Turks, and therefore likely to want to block them. On the other hand, other European countries also have interests in Libya, and a Libyan-French bloc can be decisive.

This matter will not be decided quickly. The French have been talking to the Egyptians, while the Russians have been talking to the Germans, who are attempting to play the role of mediator. The Greeks have been talking to whoever will listen, and the Israelis have been standing back to read the leaves, although Turkish-Israeli relations and competition for oil are such that their view is clear. The formal position of all these countries is that no one should destabilize Libya. The reality is that Libya is the poster child of destabilization, and the choice at the moment is between an insurgency backed by Russia and the formal government, now firmly backed by Turkey.

A New Phase

Perhaps the most interesting point, apart from Turkey’s actions, is that the precarious relationship between Russia and Turkey is coming to an end. It was never a comfortable relationship, since Turkey and Russia have been historical regional adversaries, but it worked to contain the Syrian war and to build Turkish leverage with the U.S. It may survive for a while, as each side tests the other and, at times, finds a basis for accommodation. But the Syrian issue is a submerged explosive between the two countries. Russia needs to remain in control for credibility, and Turkey is historically opposed to the Assad regime, hence the Turks’ recruitment of Syrian fighters for Libya. Of course, Turkish troops haven’t arrived yet, and much else may happen, but Turkey has declared that it has become a regional power, and its actions are driving the reactions. That itself is important.

The United States is present, but its interests are unclear. The U.S. is the decisive naval force in the Mediterranean, if it chooses to be, but it is unlikely to challenge the Turkish move. Thus far, the U.S. has been quiet. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo plans to visit Cyprus in January, but the topic of discussion will be the Eastern Mediterranean Security and Energy Partnership Act, not increased Turkish presence in the region. More important, the overriding interest in the Mediterranean is limiting Russian power. The Russians and Syrians have been conducting naval maneuvers in the Eastern Mediterranean. At the same time, the U.S. wants to retain its relationship with Turkey, particularly as it becomes a major force. But the question would be what price Turkey will want for this friendship. It is noteworthy that the United States began bombing Iranian bases in Syria and Iraq, without, apparently, informing the Russians. There is no reconciliation between Turkey and the United States but there is parallel play, for the moment at least.

We are now entering a new phase. The Turks are not so much in control of the Eastern Mediterranean but all countries in the region must take their wishes and intent seriously. They do not dominate the Mediterranean basin, but they dominate the Mediterranean’s defining issues – maritime boundaries and its oil chief among them. Most important, the maritime delimitation agreement with Libya has made Turkey the driving force in the region for now and, we think, in the long run.