Originally produced on Feb. 12, 2018 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman and Jacob L. Shapiro

In June 2014, a man named Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, dressed entirely in black, stood at the pulpit in the Great Mosque of al-Nuri in the Iraqi city of Mosul. The mosque he chose was deliberate: It was built in the 12th century by a Turkic ruler famous for fighting Christian crusaders. The name he chose was deliberate: It was a nod to Abu Bakr, the first caliph, or religious and civil leader of the Muslim world. The garb he chose was deliberate: It harkened back to the caliphs of yore and thus to the Prophet Muhammad himself. The words he chose were deliberate: Failure to re-establish the caliphate, he said, was nothing less than apostasy.

And so it was, with reverence and humility, that this shadowy figure, having declared an end to Islam’s humiliation and disgrace, resurrected an Islamic state, known now as the Islamic State. In al-Baghdadi’s own words, the “sun of jihad” had risen again.

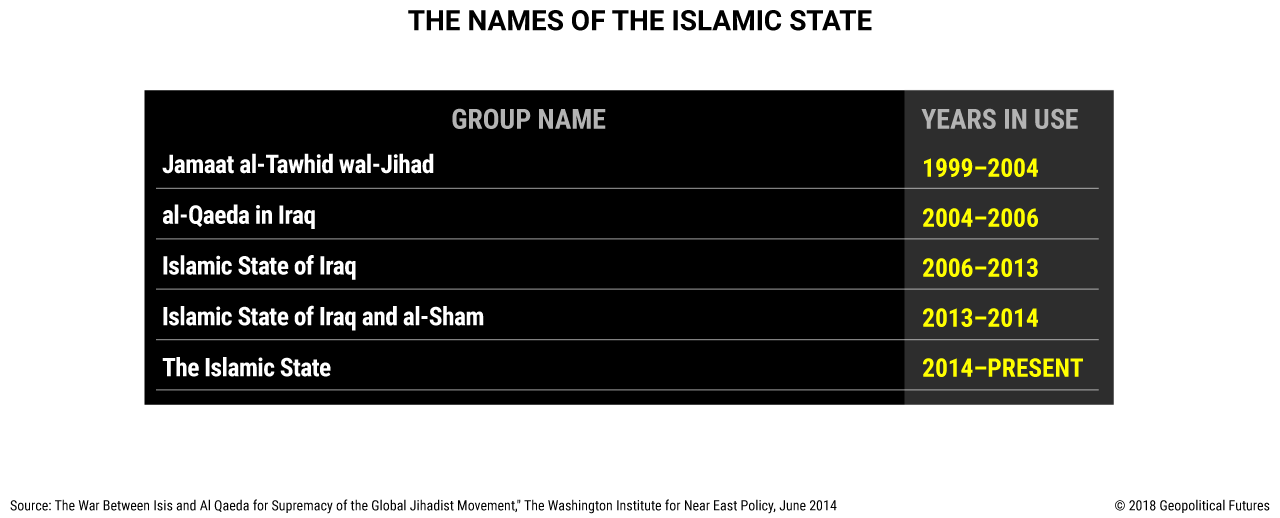

The Islamic State can be traced back to a single individual, a Jordanian man known to history as Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who became radicalized sometime in the mid-1980s. After a few unsuccessful attempts to wage jihad abroad and a stint in a Jordanian prison, al-Zarqawi hooked up with Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan. The two men would have a tenuous relationship, even after al-Zarqawi formed al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI) to fight the United States in 2004. His tactics became too brutal even for bin Laden.

When al-Zarqawi was killed in 2006, a man named Abu Ayyub al-Masri took his place. AQI was still alive, but only just. Sunni Iraqis who had initially embraced AQI chafed under its brutality. Wise to the growing hostility, al-Masri changed the group’s name twice, first to Majlis Shura al-Mujahidin, a purported Iraqi jihadist coalition, and when that collapsed after a few months, to the Islamic State of Iraq.

The cosmetic changes didn’t work. By September 2006, ISI had so angered the Iraqi Sunni population that 30 Sunni tribes joined forces to defeat them. This was known as the Anbar Awakening, a loose tribal alliance backed by the United States that sought to expel ISI from Iraq.

For the next five years, ISI barely avoided destruction. It lost contact with the core al-Qaida organization. It was weak and isolated.

Taking Advantage of Chaos

Such was the organization Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi inherited when he rose to power in April 2010. His primary goal was for the group to survive. But the troubled political environment of the Middle East enabled him to not only survive but to thrive. The Sunnis were denied a chance to form a governing coalition despite winning more seats than any other party in that year’s parliamentary elections. Iraq was frothing with sectarian violence. Meanwhile, the first demonstration in what would later come to be known as the Arab Spring took place in Tunisia and quickly spread to Iraq and Syria, where an all-out civil war eventually broke out.

ISI relocated to Syria to take advantage of the chaos, renaming itself the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, or ISIS. It entered a power struggle (which it would eventually win) with al-Qaida’s Syria franchise, Jabhat al-Nusra. While ISIS was getting settled in Syria, though, it was busy recuperating in Iraq, where it would soon begin to stage new attacks.

ISIS then did something unexpected: It began to hold territory, first in the border area with Syria and then the area around Iraq’s third-largest city, Mosul. ISIS famously took the city in just six days, after which al-Baghdadi declared the establishment of a new caliphate and renamed his group the Islamic State.

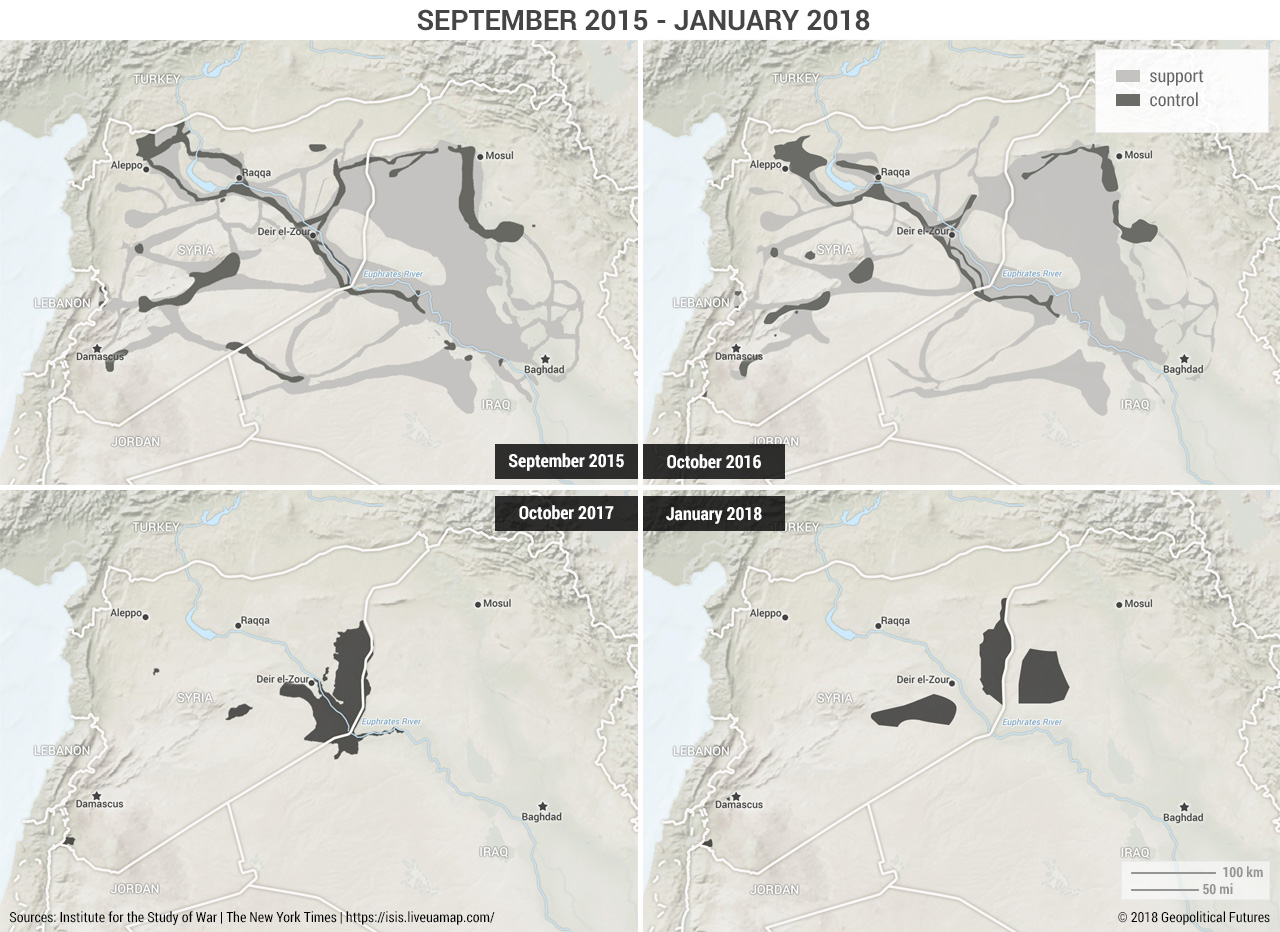

After al-Baghdadi declared the formation of the caliphate, his group undertook an offensive it had actually been planning for more than a year. IS fighters in Syria fought their way up the Euphrates River, all the way to the Turkish border, and solidified control over the areas south of Raqqa. This created a highly defensible core territory from which IS would not be easily driven.

In Iraq, IS cemented control over a number of Sunni areas on the border with Syria so that it controlled a large swath of the Syrian-Iraqi border. This allowed IS to move fighters and material back and forth across the border at will. And it conquered additional territory around Mosul to strengthen its position there.

In other words, the Islamic State was in a great position. By September 2014, IS was in control of a territory roughly the size of Great Britain. Various open-source estimates of Islamic State financial resources ranged between $2 billion and $3 billion. And IS controlled oil fields that could bring in an additional $1 million–$2 million daily. The Islamic State started to resemble an actual state. It levied taxes, managed social services, hired police forces, and established schools. It held territory not for strategic advantage but for direct administration.

Down but Not Out

But the Islamic State’s fall would prove to be as quick as its rise. Savvy though it may have been, it would not have been able to accomplish what it had were it not for the relative indifference of countries such as the United States, Russia, Turkey, and Iran, which had not considered the group much of a threat. But now that IS held real territory, the Islamic State was a real threat to their interests, and soon these larger powers would conspire, if not outright ally, to bring the group down.

The group is down but not out. It has conceded much of its territory, including its capital of Raqqa. But it has not conceded defeat.

That’s not to say IS intends to abandon the territorial gains it has made in Iraq and Syria. It would not have endeavored to claim them if they were unimportant to its goals. But territory is a luxury, not a necessity. The restoration of the caliphate was, in effect, a restoration of Muslim dignity.

All of this hints at what the Islamic State’s next target may be: Saudi Arabia, the steward of Islam’s holiest sites. The country is religious; women must be accompanied by men in public and must cover their faces, and punishments for crimes are derived from Islamic law. But if you’re a fundamentalist, it’s hard not to question Saudi piety. The royals who govern the country live lives of opulence. They drive expensive cars and host debauched parties, rife with alcohol and attended by prostitutes. The Islamic State looks at Saudi Arabia and sees a bunch of hypocrites.

In this hypocrisy the Islamic State sees opportunity. Saudi Arabia is weak and troubled, but more important are the regional dynamics in play. Now that the Islamic State is in retreat, Iran, the de facto leader of the Shiites, is expanding its influence. Saudi Arabia, the de facto leader of the Sunnis, has framed itself as the dam that will stop the rising tide of Iran. The Islamic State has frequently and effectively used sectarian rivalries to its advantage, and there is no bigger sectarian rivalry in the region than the one between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

The Islamic State may be quiet, but there’s no reason to believe it’ll be quiet for long.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East