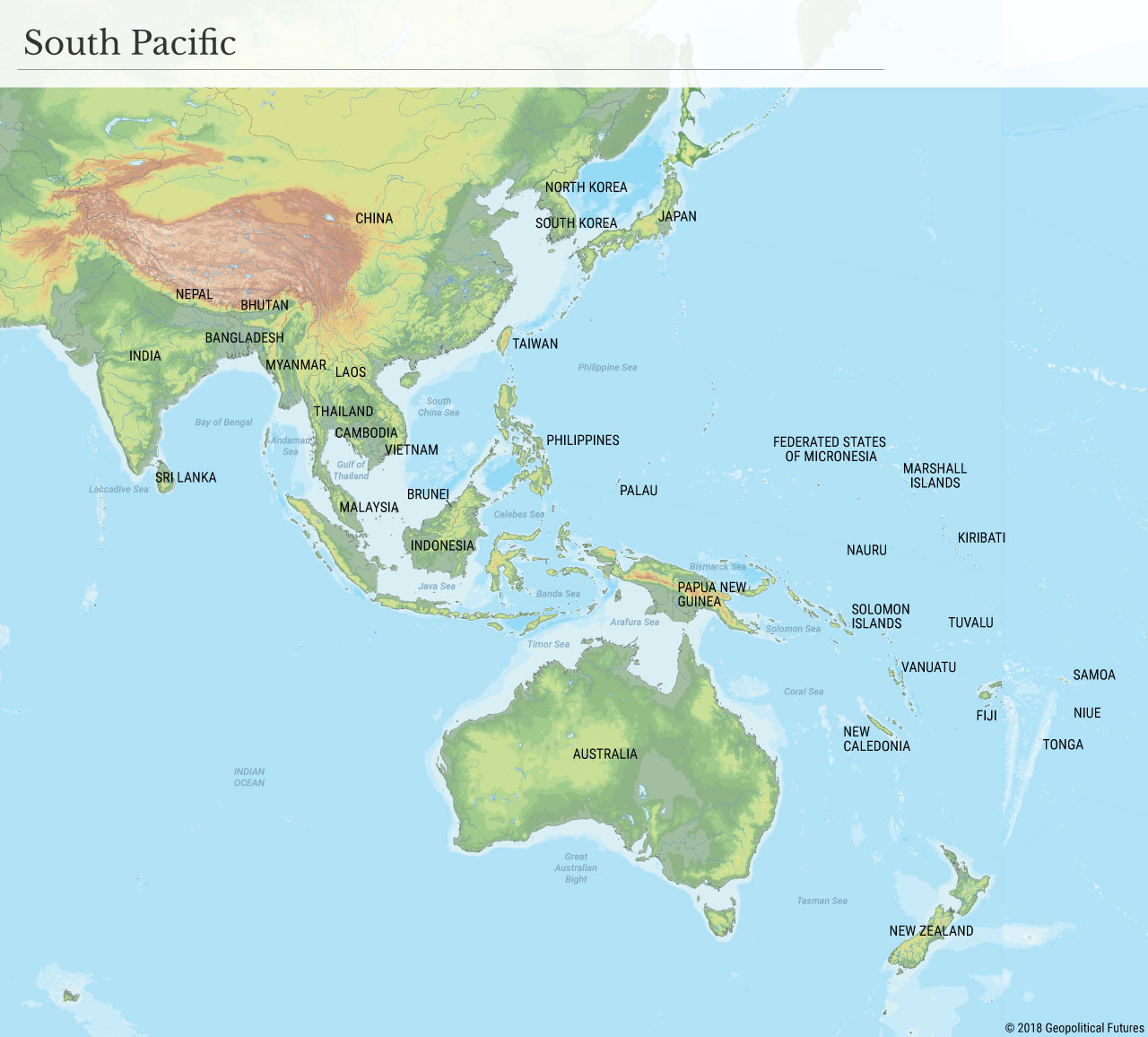

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. visited Washington last week, where he signed what is essentially a collective defense agreement. In doing so, he sealed their bilateral relationship just a few weeks after signing another agreement that allows the U.S. to station troops and aircraft at bases in the Philippines. The alliance creates a serious problem for China, whose fundamental interest is having unfettered access to the Pacific Ocean and thus unencumbered global trade.

At roughly the same time, Taiwan and Japan held a meeting to plan the coordination of forces in the event China attacks Taiwan. That Beijing immediately condemned the meeting emphasized its significance. The fall of Taiwan would be a serious threat to Japan’s access to the Pacific and possibly a threat to the Japanese mainland. These threats may be far-fetched, but a Chinese occupation of Taiwan graduates them from non-existent to at least theoretical.

Japan has been in the process of expanding its military for some time, and obviously a joint Japanese-Taiwanese force would necessarily include the United States. There are also indications that South Korea would participate.

The new map of the Western Pacific thus puts China in a very different position. An invasion of the Chinese mainland by any new coalition is still impossible given the size and sophistication of Chinese land forces. But China’s difficulties in securing guaranteed access to the Pacific and its regional waters have soared. The ability of Japan and Taiwan to intercept Chinese naval movements, combined with the United States’ and Australia’s ability to block Chinese movement to the south, is a problem for Beijing. The obvious vulnerability of the coalition is that it has shown its hand and undoubtedly has not fully completed its defenses. China could preemptively strike any one of the coalition partners in theory, but the narrowness of the waterways makes the risk of defeat high.

There is evidence that China understands the severity of the situation. President Xi Jinping recently moved Zhao Lijian – an official who came to embody China’s aggressive and confrontational wolf warrior diplomacy – from a spokesman role to head of the Foreign Ministry’s Boundary and Ocean Affairs Department. This will herald a significant, if not radical, shift in Chinese foreign policy. Indeed, the Taiwan News outlet recently reported that top Chinese diplomat Wang Yi outlined new policies for Taiwan, saying that the old ones must be reconsidered.

Our view is that though China’s systemic internal problems make it weaker than its military and economic stature suggest, it’s still a major power that can, under the right circumstances, assert power far from its shores. But these are not the right circumstances. The geography of the Asia-Pacific is changing to Beijing’s detriment. China has made gestures toward a policy shift. It remains to be seen whether China’s internal politics allow it to be this flexible.