Russia spent much of 2021 trying to reestablish the buffers it lost after the collapse of the Soviet Union. It deployed troops to its western border with Ukraine, increased integration with Belarus, continued its peacekeeping mission in the Caucasus, and deepened cooperation with Central Asian nations. In 2022, Moscow will shift its focus to a country in the South Caucasus that has been balancing between the West and Russia for years: Azerbaijan. And it will do so by using the Eurasian Economic Union, a post-Soviet regional bloc that it dominates, as a tool of coercion.

Hidden Hand

Last month, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev visited Brussels at the invitation of the NATO secretary-general. During their meeting, Aliyev said Azerbaijan is a reliable partner of NATO and maintains close ties with NATO allies, especially Turkey. Comments like these irritate the Kremlin, which wants to limit NATO’s presence along its periphery as much as possible. Azerbaijan is a critical part of this strategy, as it separates Russia from NATO forces in Turkey.

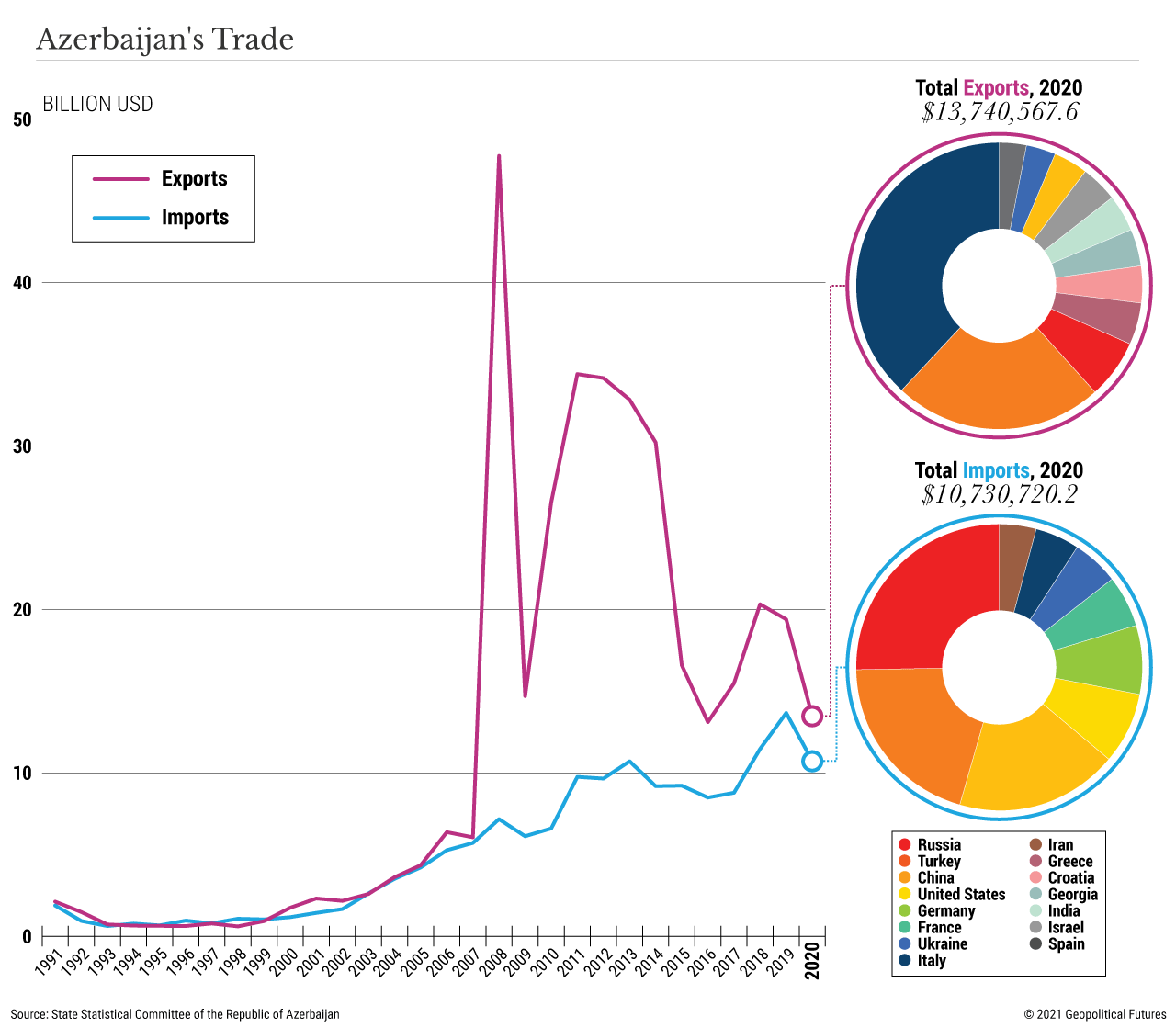

Of late, Moscow has used a combination of economic cooperation and military involvement (in the form of its peacekeeping operation in Nagorno-Karabakh) to maintain its foothold in the Caucasus. But considering its deepening economic problems and assortment of other priorities, Russia’s ability to compete for economic influence here is weakening. For example, it accounts for only 5 percent of Azerbaijani exports, while Italy and Turkey (both NATO countries) account for 30 percent and 18 percent, respectively. Baku is also increasing military cooperation with Turkey, which supported Azerbaijan in the 2020 war in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Moscow, however, has a hidden hand to play. Azerbaijan is highly dependent on oil and gas exports to the West. Today, about 68 percent of the country’s total exports are crude oil and related products, and 15.9 percent are petroleum gases and other gaseous hydrocarbons. The Kremlin, which understands better than most the pitfalls of relying so heavily on energy exports, is likely anticipating that Baku will want to diversify its overseas sales to reduce its economic vulnerability. But this will be difficult for a country like Azerbaijan, considering the level of competition and lack of demand for its non-energy products. Thus, on the eve of the Azerbaijani president’s visit to Brussels, the Kremlin reminded Baku of the benefits of its partnership.

Just days before Aliyev was set to leave for the NATO meeting, the honorary chairman of the Eurasian Economic Council, a regulatory body of the Eurasian Economic Union, said Azerbaijan could gain observer status in the bloc, whose membership includes Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia. Joining the bloc’s customs union could have significant benefits for Azerbaijan, which receives about 18 percent of its imports from Russia.

Moscow has also given subtle hints elsewhere of the advantages of its cooperation. Various Russian media publications have recently been touting the strong ties between Azerbaijan and EAEU members. For example, the Azerbaijani affiliate of Russia’s Sputnik News website printed an article last month highlighting the benefits of membership. According to the publication, Azerbaijan’s accession to the EAEU would increase the country’s agricultural and non-oil sector exports by $280 million. It also claimed that membership could increase Azerbaijan’s gross domestic product by 0.6 percent over current levels, and that every resident of Azerbaijan would profit by $1,013 – a substantial amount in a country whose per capita GDP is just $4,202.

The Kremlin also recently mentioned a 2018 survey by the Analytical Center for the Government of the Russian Federation that found that almost 40 percent of Azerbaijan’s business community would welcome closer economic relations with the EAEU. These numbers, the Kremlin hopes, will sound enticing in a country whose economy is recovering from the pandemic, but slowly. Although Azerbaijan suffered from the economic effects of the pandemic less than its neighbors – due largely to its energy exports – unemployment, poverty and emigration (mainly to Russia) remain significant problems.

However, Russia knows that it can’t rely solely on the EAEU’s internal market to attract Azerbaijan, since the economies of some of the bloc’s other members are also struggling. Thus, the EAEU is in talks on a permanent free trade agreement with Iran. (The two parties signed an interim trade deal in 2018.) The bloc also has free trade agreements with Serbia, Vietnam and Singapore, and by 2025, India, Israel and Egypt will be added to the list. This means that by joining the bloc, Azerbaijan will gain access to a number of additional markets, not just those of its five members.

Another benefit is that it would help tame hostilities with Azerbaijan’s historical rival, Armenia. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said his country would not oppose Azerbaijan’s accession if it would contribute to regional peace. The statement is a clear olive branch given the frequent clashes between the two countries.

Obstacles

But there are also obstacles in Russia’s path to pulling Azerbaijan into the EAEU. First, acquiring membership, or even observer status, can be a lengthy process that requires consensus among all EAEU members. Given the legal requirements of joining the bloc, as well as the ongoing tensions with Armenia, negotiations could get complicated. Moscow may have to cater to Azerbaijan for a while to keep it interested, which is difficult to do given the competition in the region.

Second, Baku must consider the reactions of its other allies. Azerbaijan is increasing trade with European countries and close allies with Turkey. It prefers to balance between the West and Russia, rather than taking sides.

Third, the EAEU has internal problems of its own. Member states disagree over a number of issues, and aren’t always willing to concede in order to bridge their divides. It’s also competing for influence with the Commonwealth of Independent States, another Russian-led institution that consists of post-Soviet nations. In addition, the EAEU’s common market is still evolving, with issues over the functioning of the common gas and energy market and migration from less developed to more developed countries.

Ultimately, Azerbaijan must see the benefits of joining; average Azerbaijanis must support the integration process; and there must be no limits to the free movement of goods, even through the conflict-ridden Nagorno-Karabakh region. Without these conditions being met, Azerbaijan is unlikely to want to join the bloc. It’ll be difficult to achieve in the medium term, but for Moscow, this is the best time to make its move, as Baku looks for reliable partners to revive its economy and its traditional partners are mired in their own problems. Pulling Azerbaijan into the EAEU would be a victory for the Kremlin. It’s not an easy path, but it’s one Moscow will follow throughout the coming year.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East