Originally produced on Nov. 14, 2016 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

George Friedman

The U.S. presidential campaign contained a constant undertone of Russia and President Vladimir Putin. Putin said nice things about Donald Trump, and Trump about Putin. In fact, there is a small faction of Trump supporters that admires Putin for being a strong leader and for his position on gay rights and other matters. They do not see him as a former communist, but rather as a defender of Western civilization.

The U.S. also claimed that Russian intelligence tried to facilitate Trump’s election by hacking the emails of the Democratic National Committee and John Podesta, Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman.

All of that is done now. Russia is Russia, the United States is the United States, and serious matters must be dealt with. To begin, we need to understand what real issues exist between the U.S. and Russia. And at the heart of the matter is Ukraine.

The Russian view of what happened in Ukraine is that the U.S. engineered an uprising in Kiev that drove out the legally elected government. The U.S. says it did not engineer a coup, but it did support human rights activists opposed to a corrupt government in Ukraine. The Russian response is that the current government is no less corrupt.

The National Security Argument

After the change in Ukraine’s government, the Russians took formal control of Crimea and tried to foment an uprising in eastern Ukraine. It was contained by the Ukrainian military but not crushed. The Americans charged that the Russians were interfering with the internal affairs of the Ukrainian nation. The Russians responded that the U.S. was audacious in making the claim.

In addition, the Russians pointed out that historically, Crimea had been part of Russia and was transferred to Ukraine in the 1960s. The Russians also had a treaty with Ukraine allowing control over the naval base in Sevastopol in Crimea. This base is vital to Russia’s national security. With an anti-Russian government in Kiev, Russia was protecting its rights under the treaty.

As for the uprising in eastern Ukraine, the Russians said it was a predominantly Russian region whose rights had been dismissed by the Ukrainian government. Russia said it wasn’t involved in a movement to establish a degree of regional authority, as had been done by ethnically distinct regions in many countries.

The U.S. claimed the Russians were not only arming and directing the rebellion, but also had military designs on the country. So, the U.S. and Europe placed sanctions on Russia. Russia demanded the sanctions be removed.

All this can be summed up by two charges. The Russians claimed the U.S. was financing activists masquerading as human rights groups in order to destabilize those countries it wanted to control. Russia claimed that the goal of the U.S. was to install pro-U.S. regimes.

The U.S. claimed the Russians were becoming internally more repressive and returning to the dictatorship that had existed in the Soviet Union. To the U.S., it appeared to be a matter of national sovereignty and liberal democracy. U.S. President Barack Obama and Clinton’s insistence that this was the extent of U.S. involvement was matched by the Obama administration’s fear that Putin was trying to recreate the former Soviet Union with a new ideology. Each claimed the other was aggressive and hegemonic.

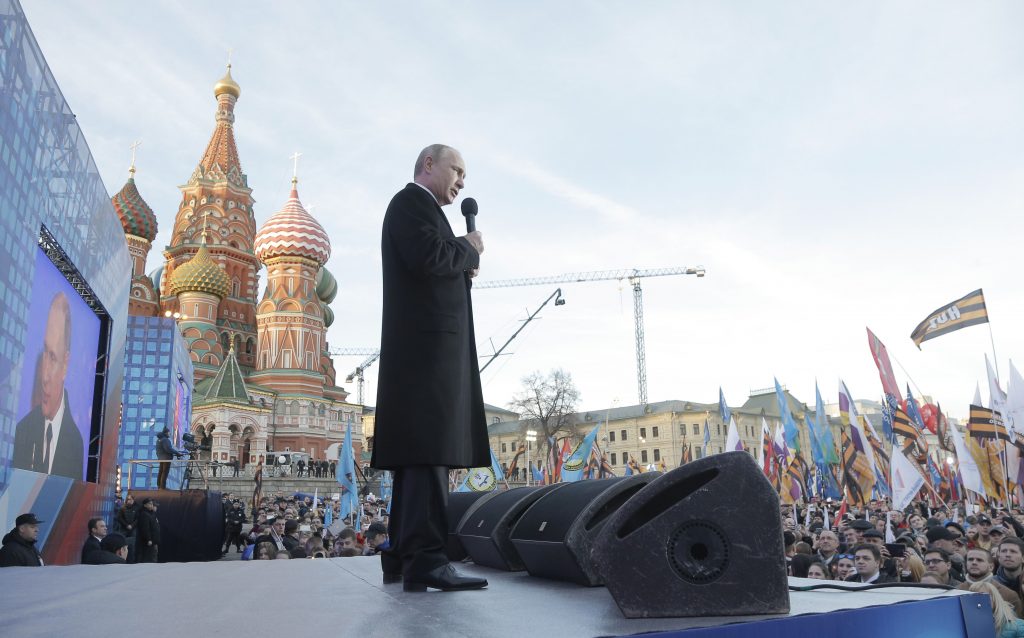

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin gives a speech by the Kremlin Wall in central Moscow on March 18, 2015, to mark one year since he signed off on the annexation of Crimea in an epochal shift that ruptured ties with Ukraine and the West. MAXIM SHIPENKOV/AFP/Getty Images

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin gives a speech by the Kremlin Wall in central Moscow on March 18, 2015, to mark one year since he signed off on the annexation of Crimea in an epochal shift that ruptured ties with Ukraine and the West. MAXIM SHIPENKOV/AFP/Getty Images

Historical Buffer

A level beneath this also existed. Russia had survived for almost three centuries because of strategic depth. Historically, control over the Baltics, Belarus, and particularly Ukraine had been essential for Russia’s survival. Without this buffer zone, Napoleon, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and Adolf Hitler would have destroyed Russia.

The U.S. move into Ukraine was therefore a fundamental challenge to Russian strategic interests (the Russians were less concerned by Europeans). Further, because the U.S. knew it was a strategic challenge, it increasingly seemed that the Americans sought to destabilize Russia itself. A pro-U.S. government in Ukraine (with forces trained and supplied by the Americans) was not acceptable.

For the past century, the U.S. has had a consistent and fundamental strategic interest. If all of Europe united under a single hegemonic power, it would pose a threat to the survival of the U.S. Russian natural resources and manpower coupled with Western European technology and organization could more than match U.S. power. U.S. national security depended on control of the seas, which permitted American commerce and prevented foreign invasion. The only force that could challenge U.S. Naval power would be a united Europe.

The U.S. intervened in World War I in 1917, when it appeared the Germans had defeated Russia and were about to defeat the French and British to control all of Europe. The U.S. fought in World War II to prevent another German conquest of Europe. The Cold War was designed to prevent a Soviet conquest and amalgamation of Europe. The U.S. had to prevent the re-emergence of Russia as a potential hegemon.

Two geopolitical imperatives collided in Ukraine, clothed in a debate over human rights, national sovereignty, and charges of imperialism. Beneath all of this noise, the reality was that Russia could only regard U.S. actions in Ukraine as an attempt to cripple or destroy Russia. The U.S. was afraid that with Ukraine under Russia’s control, Russia would be able to slowly extend its influence among former satellites, and from there, into the center of Europe.

Subjectively the debate might have been about other things. Sometimes, political leaders don’t realize the stakes and proceed on an automatic path of action and response. Sometimes, they understand the issues quite clearly. In either case, as in economics, there is an invisible hand in geopolitics. Putin dismissed the human rights claims and saw Americans engage in making Russia incapable of defending itself. The U.S. dismissed Russia’s claim that it had violated Ukrainian national sovereignty and focused on the potential threat that Russia could pose to Europe.

The U.S. began working with Poland and Romania to build a defensive line. The Russians began an expensive process to create a more powerful military force. Then oil prices collapsed, and Russia faced an even deadlier situation.

Russia failed to develop a modern economy after 1992. It remained, like the Saudis, an energy exporter. And when the price of oil crashed, the Russians faced an economic crisis. The Soviet Union collapsed when defense expenditures rose and energy prices declined in the 1980s. That same configuration confronted Russia again, and Russia faced an existential crisis.

Putin first had to maintain national morale. He had to demonstrate that regardless of economic problems, he had made Russia a great power. He was not in a position militarily to wage war in Ukraine, but he was in a position to appear powerful. Engagement with American and European aircraft and ostentatious military exercises near borders increased the sense of Russian power at home and abroad.

This was the key to Russia’s involvement in Syria, which had no strategic value to the Russians. The U.S. could easily isolate or destroy a naval base there, and Bashar al-Assad meant nothing to Putin. But the intervention in Syria allowed Putin to appear to be engaging the U.S. on equal terms in a place where the likelihood of a clash appeared great, but had little chance of happening. Putin needed to buy time for his military to mature, or oil prices to rise, or both. Neither was likely to happen quickly.

An unofficial truce took hold in Ukraine. The Kiev government remained in place, Russia held Crimea, and fighting in the east was reduced to a low, yet constant, level. A reality had been produced. For Putin, this was not an unreasonable basis for an agreement.

Mutually Beneficial Agreement

A formal agreement would recognize the current Ukrainian government and accept its Western orientation. It would also bar U.S. military aid and troops from Ukraine. The Russians would withdraw support for rebels, but they would be granted a degree of autonomy. Crimea would be a postponed issue (or one of those eternal diplomatic processes designed to appear that a problem is being addressed without actually addressing it). Russia would redeploy forces away from a threatening posture toward Ukraine, something it would be happy to do given Russia’s military constraints.

In effect, Ukraine would be neutralized, Russia would have made major concessions, and the U.S. wouldn’t have to be concerned about a Russian move to the West. If either side broke the agreement, there would be time to respond. Ukraine is large. The problem is that the Obama administration was content with an informal reality and had no desire to give Putin the appearance of a victory.

Putin read this move as a desire to bring him down. That may have been on the administration’s mind, but distrust of Russia coupled with a lack of urgency meant endless conversations between U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, with no progress.

Putin’s interest in Trump derived from Trump’s lack of interest in foreign adventures and indifference to creating liberal democracies around the world. Trump’s argument is that the U.S. needs an overriding interest in an area to engage. Given this position, he likely would acknowledge that Russian hegemony over Europe is unacceptable, but he would not plan to engage so early and so deep in a region of Russian interest. For Trump, a neutralization of Ukraine would be acceptable. The personal dimension, Putin hoped, would eliminate Obama’s desire to see him fall.

Beneath the jabber of the campaign (to which Trump contributed far more than his fair share) and the mutual public charges and counter-charges, the situation between the U.S. and Russia can be explained. The basis for a mutual agreement emerges from that explanation. The reality is that Russia is not in a position militarily to conquer Ukraine, nor is the U.S. in a position to defend it. As long as the Russians don’t return to the Carpathian Mountains and the U.S. doesn’t go east of the Dniester River, no alarm bells need to be rung. Both sides know that conflict in the future is possible, but neither is ready for it now.

Trying to figure out Trump’s and Putin’s thinking is not easy. Intentions are buried under layers of bluster. But intent is clearer than many might think. It would be a quick success for both sides and would strengthen two weak political hands.