By Jacob L. Shapiro

On Aug. 12, two important reports were published on the current state of the Chinese economy. The first was the International Monetary Fund’s annual review, which said the outlook for near-term growth had improved and then in virtually the same breath pointed out that corporate debt is rising and capital outflows for 2016 will equal 2015’s at $1 trillion. The second report was China’s monthly release of investment data, which showed that fixed asset investment growth in China slowed to 8.1 percent in July. According to Caixin, that’s the slowest year-to-date fixed asset investment growth China has seen in 16 years.

The juxtaposition of these two reports helps us trace the contours of the problems that the Chinese economy faces. It shows how these problems are ultimately not about just facts and figures but rather are about politics. The IMF report’s proposed mitigation efforts make it all sound very easy – reduce corporate debt, restructure or even liquidate state-owned enterprises (SOEs) exhibiting subpar performance and accept lower growth. But for China, as in many countries, economic policy decisions like this are fraught with political consequences that often prevent the goals from being realized.

The Chinese government has identified the need to reform SOEs. It is a common talking point for President Xi Jinping these days. The Chinese government has gone so far as to say publicly that it will eliminate 1.8 million jobs in the overstocked coal and steel sectors, though the timeline for the elimination of those jobs has always been indeterminate. However, that is not good enough for the IMF. The IMF suggests that China cut 8 million jobs in a few key sectors. This is simply not something that China can just do – the social and political costs outweigh the economic.

The corporate debt problem is similar. One of the key issues the IMF report identified is the intensity at which credit growth has accelerated. The regions that have seen the highest levels of credit growth are largely the northeastern and north-central provinces, where industry is the main driver of the economy. Such credit growth is not specifically in keeping with the party line – Premier Li Keqiang spoke to provincial governors in July and exhorted them to eliminate inefficiencies, i.e., not to lend money to SOEs that are struggling to make ends meet.

China is an authoritarian state, but that does not mean that the central government can simply dictate what it wants to local authorities and have it be done. In a sense, the system is built on the lower-ranking party members profiting from their activities. Real reform, on the other hand, is contingent on many of those local officials taking a long-term view rather than short-term view. That is easier to do from IMF headquarters or even from Beijing. It’s much harder for a local official in Shanxi or Heilongjiang to allow SOEs to fail and protests to break out because millions are losing their jobs.

This is not, however, just a center-periphery divide. The central government is caught between continuing to encourage growth to maintain employment and accepting lower growth while boosting domestic consumption. The monthly investment numbers released by the Chinese bear this out. The monthly release is a stark data point of a trend that began roughly around December 2015.

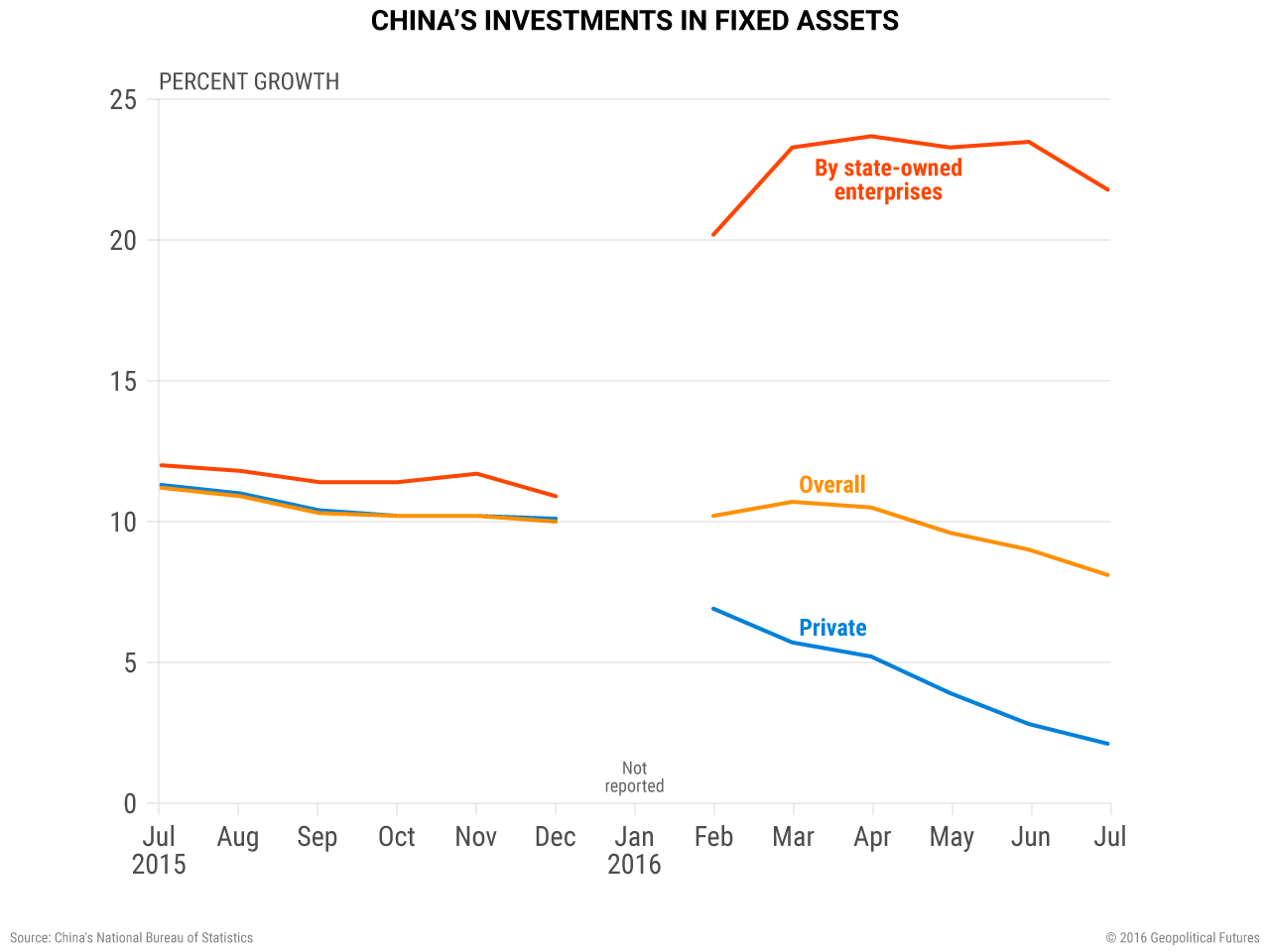

As the graph above shows, before December 2015, the percentage growth between investment in fixed assets by SOEs and by private enterprises was roughly equal. (In absolute terms, private investment accounts for roughly 60 percent of all investments.) January, however, was a rough month for the Chinese economy, as shocks in the stock markets severely weakened investor confidence. In response, China relied on stimulus – more stimulus in the first quarter of 2016, in fact, than any other quarter since the 2008 financial crisis.

The graph above is one example of that stimulus. Private investment in fixed assets has slowed precipitously to just 2.1 percent growth in the month of July. This is despite China’s State Council issuing new guidelines in June to try and stimulate private investment, with measures ranging from simplifying approval mechanisms for potential investments to permitting investors to go to corporate bond markets to raise funds. Also, just last month the government eased investment rules in free trade zones in China, granting foreign investors permission to found companies in various sectors, including iron and steel production, that would not have to be co-owned by any Chinese interests.

Meanwhile, SOE investment in fixed assets doubled between November and February (China did not report any data for the month of January). Though that growth slowed slightly in July, it is still at 21.8 percent – well above the levels of SOE fixed asset investment growth before China began pumping money into the system. Chinese companies are already depending more and more on borrowing money just to service prior loans; a Goldman Sachs report last month estimated that the debt service ratio for China was just around 20 percent. These are the very SOEs that China says it wants to restructure and the IMF says China should reform. China, however, has no choice but to use these SOEs to prop up economic growth at its current levels and to attempt to stimulate the domestic economy.

The IMF projects that Chinese GDP growth will fall slowly, from 6.6 percent in 2016 to 5.8 percent in 2021. It makes these projections assuming that China is going to be able to pass and implement many of the reforms it suggests. The Chinese government is motivated to make many of these reforms and it will try, but its constraints force it to do this with one hand tied behind its back. One of the reasons Xi is consolidating so much power in his office is that he knows that China must change, and that Beijing must have power to do it. But even a powerful Xi cannot eliminate corporate debt or conjure 8 million jobs out of thin air.