Saudi America: The Truth About Fracking and How It’s Changing the World

By Bethany McLean

The economics of the oil industry can be a bit confounding. Were oil any other commodity, it would, I imagine, more faithfully abide by the laws of supply and demand than it seems to. If too much supply drives prices down, and if producers want high prices, it stands to reason that they would produce less. But when prices famously crapped out in 2014, did OPEC lower production? Did Russia? Did the United States, whose vast shale oil reserves were as responsible as anything else for flooding the market?

The answer is no, not really, because it’s not as simple as supply versus demand. OPEC would announce production cuts a couple years later, and some of its members may have even honored their commitments on occasion, but by and large they kept oil flowing, figuring it was better to maintain market share than to lose it to the wildcatters in the U.S. or to Iran when it brought production back online.

The thing is, oil is not any other commodity. Plenty of other resources are vulnerable to price fluctuations, but few are so important as oil, and fewer are as finely attuned to geopolitical forces beyond their control. That’s partly because of geography. Much of the world’s recoverable oil is located in the most restive regions on earth. Yes, technological advances have unlocked oil reserves in places where extraction was once thought impossible, but as a producer, the Middle East still (collectively) reigns supreme. The region is obviously unstable, ravaged as it has been by decades of insurrection and foreign invasion, economic inequality and domestic unrest, sectarian and ethnic violence. It’s fair to argue that the presence of oil is at least somewhat responsible for the Middle East’s turpitudes, but it’s not solely responsible, and in any case that’s not the point. The point is that the presence of oil, rightly or wrongly, gives Middle Eastern governments geopolitical weight that the presence of, say, potash simply would not. (No offense to the fine purveyors of potash out there.)

Contributing to the quirks of supply-side economics of oil is finance, an area that receives less attention than it should, argues Bethany McLean, author of “Saudi America: The Truth About Fracking and How It’s Changing the World.” She covers a lot of ground in a pretty short amount of time – at about 130 pages, the book is better thought of as a nonfiction novella – paying particular attention to the so-called U.S. shale revolution but also venturing into the geopolitical implications of a changing oil industry. She uses Aubrey McClendon, the now-deceased former head of the Chesapeake Energy Corp., to tell the story of how the U.S. got to where it is now, and though he is the perfect engine for the tale, he’s not really what struck me about the book. What struck me is the financial precariousness of the entire U.S. shale industry.

I don’t want to get too bogged down in data. Suffice it to say that fracking a shale well requires vast amounts of capital. Land and mineral rights must be purchased, surveys must be conducted, and, in time, wells must be serviced – a process that entails the hiring of labor, the renting of a rig, the procurement of chemicals, sand and other ingredients needed for fracking, and so on. That’s a lot of money for wells that may not actually prove out. But even if they do, the rate of decline on fracked shale wells is so much steeper than conventionally drilled wells that they require more capital each year to maintain. Writes McLean, “One energy analyst calculated that to maintain production of 1 million barrels per day, shale requires up to 2,500 wells, while production in Iraq can do it with fewer than 100.” Goldman Sachs believes that by 2023, it will cost $58 billion in capital investment just to keep fracked shale production flat.

All this has led to massive amounts of outside investment and, of course, to massive amounts of debt. A fellow at Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy estimated that by 2014 the shale industry’s net debt exceeded $175 billion, according to McLean. Between 2006 and 2014, a time when the price of oil reached a historic high, only five of the 16 largest publicly traded frackers were able to generate positive cash flow. They burned through their investments, spending $80 billion more than they sold. (In 2017, U.S. frackers raised $60 billion dollars in debt, up 30 percent from the previous year.)

Why, then, are investors willing to throw around so much money? McLean convincingly argues that the shale revolution couldn’t have happened were it not for the 2008 global financial crisis. After the recession, the U.S. government needed to stimulate the economy, so it slashed interest rates and made money much cheaper to borrow. It also encouraged pension funds in need of returns to invest with hedge funds that invest in high-yield debt. The industry wasn’t growing by much, but, in the eyes of investors, growth was growth, and they’d take it wherever they could find it.

McLean believes that as soon as rates go back up (as they inevitably do) this house of cards may come tumbling down. She believes that the most important thing for the future of shale is the same thing that led to the revolution: the availability of capital. I, for one, believe her.

Cole Altom, managing editor

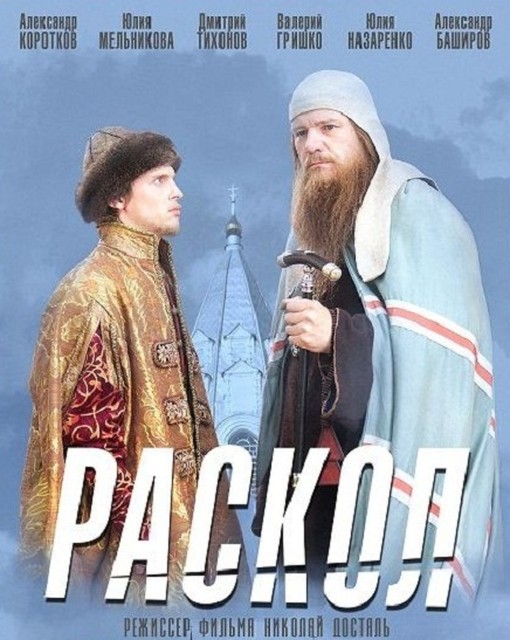

Raskol

Directed by Nikolai Dostol

The New Year and Orthodox Christmas holidays are rather long in Russia – and cold. What better way to pass these leisurely, snowy days than to stay in and watch a good historical drama? Russia turns out no shortage of historical series, one of the most successful genres in the country, so I had plenty to choose from. “Raskol” (or “Schism”), a 20-episode drama from director Nikolai Dostal, stood out for its treatment of one of the most difficult periods in Russian history – a chapter that still resonates today.

Between the tumultuous rule (and ensuing upheaval) of Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century and the triumphant reign of Peter the Great in the late 17th century, the intervening era in Russia’s history is easy to overlook. But the schism that rocked the Russian Orthodox Church in the mid-17th century is an important theme in Russia’s evolution. In 1667 the church was split among the supporters of Patriarch Nikon and the Old Believers, who rejected his reforms. The various proceedings in the church touched all aspects of life in Russia in the 17th century, though the country was on its way to secularization, so the effects of the split were far-reaching: The schism broke the church’s traditional foundations, challenged moral values and led to a rift in the political and social realms, as well as the religious one. Some historians believe that the events of the period changed Russia’s very cultural code.

A few centuries later, the Russian Orthodox Church is now undergoing a different kind of split. The Orthodox leadership proclaimed the creation of an independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church in December 2018. The process isn’t over, but the backlash has already begun. Attacks on Orthodox churches have become more frequent in Ukraine, and the decree has given Kiev and Moscow more fuel for their disagreement. A religious war may yet become the schism’s most dire consequence.

“Raskol” is an impressive project, both for the subject matter it tackles and for its execution. The series, filmed in numerous locations across the vast Russian territory, and has received praise for its attention to historical accuracy in set and costume. And through the wonders of the modern era, it’s available for free online viewing, complete with English subtitles.

Ekaterina Zolotova, analyst

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President