By Phillip Orchard

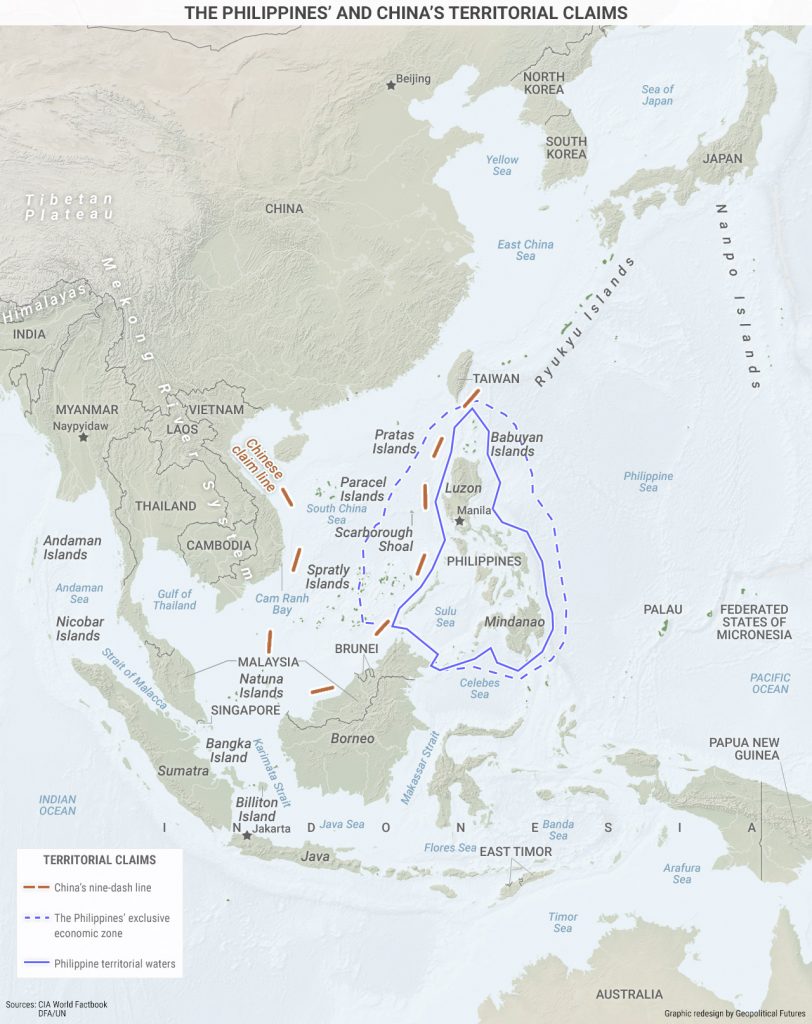

Over the past month, nearly a dozen Chinese naval, coast guard and maritime militia vessels have been spotted around Pag-asa Island, one of the few Philippine-occupied masses in disputed parts of the South China Sea. Chinese ships were also seen around Sandy Cay, an unoccupied sandbar located between Pag-asa and nearby Subi Reef, one of seven Chinese-made, fortified islands in the Spratly archipelago. The Chinese fleet reportedly stopped a Philippine government vessel from approaching the area. An opposition lawmaker with close ties to the military showed evidence Aug. 29 that China had planted its flag on another nearby cay.

The incident, which came shortly after Manila claimed to have reached an understanding with Beijing on the territorial disputes, has become politically explosive in Manila. Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and his Cabinet have come under fire from the Philippine opposition – and, most important, the military – to find a way to stand up to Beijing. But Duterte and his foreign minister have remained dismissive of the issue. On Aug. 28, the president said Beijing was merely patrolling the area “as friends” and had promised him that it would not build on the sandbar. Notably, he also said he would not invoke the mutual defense treaty with the U.S. in the event of a confrontation with the Chinese, citing his loss of faith in the Americans. In other words, Duterte is saying a verbal promise from Beijing can be trusted, while the 66-year-old treaty alliance with the U.S. cannot.

Duterte is playing a high-stakes game. He’s trying to position his country to benefit from the competition between China and the United States — a contest in which the Philippines plays a singularly important role – while also balancing the Philippines’ traditional centers of domestic power. In this game, as in all geopolitical games, promises and partnerships are only as strong as what reinforces them. China’s promise is flimsy, but its intentions have been made clear. The U.S. partnership is enduring but limited in scope and applied selectively on U.S. terms. Combined, they leave little room for the Philippines to act in its own interest.

China Sets Its Terms

Chinese ships are no strangers to waters around disputed features in the South China Sea, but the political sensitivity of Pag-asa and its adjacent features has compelled the Chinese to steer clear. Pag-asa, after all, is home to a permanent civilian presence, making it the Philippines’ most valuable Spratly possession. Earlier this year, Duterte made a big show of securing the area, ordering the construction of fortifications on Pag-asa and pledging to personally plant the Philippine flag on unoccupied features like Sandy Cay.

His downplaying the current encroachment, citing only the spoken agreement from Beijing, is not evidence that his so-called pivot away from the U.S. has compelled China to soften its position on its South China Sea claims. Any promise like that would be strategically worthless. China needs a lasting political accommodation with Manila to ensure its access to Pacific export routes, and it cannot yet go head-to-head with the U.S. Navy. And yet China has built up and militarized seven reefs relatively close to Philippine shores. China’s relationship with Manila is arguably no worse today than it was when it began to occupy the features, and no one has pushed back enough to make Beijing change its mind.

In Manila, anti-China protesters march in response to China’s presence in disputed waters in the South China Sea. TED ALJIBE/AFP/Getty Images

In Manila, anti-China protesters march in response to China’s presence in disputed waters in the South China Sea. TED ALJIBE/AFP/Getty Images

China is betting that its military superiority to the Philippines, as well as Manila’s doubts over U.S commitment, will discourage the Philippines from a confrontation, make the case for cooperation and create an opening for a lasting accommodation. Without such a deal, China will happily break its promise to Duterte and expand farther into Philippine waters. Duterte has little ability to bring Beijing to the point where its pledges are rooted in a broad alignment of interests.

Boxed In

But neither can Duterte give the Chinese what they would demand — namely, the expulsion of U.S. forces and likely basing access for Chinese forces — in exchange for backing off Philippine claims in the South China Sea, even if he wanted to. This is because the Philippine public is starting to question his outreach.

It’s not that the Philippine public would reject an accommodation with China out of hand. The Philippines has rarely seen itself as a country that can control its own fate. But it becomes an issue if the president and his backers are seen as selling out Philippine sovereignty for personal gain. That several wealthy supporters of the president are well-positioned to profit from Chinese-backed infrastructure projects and joint oil exploration projects around Reed Bank makes his outreach particularly risky.

The political risk is magnified if Chinese promises come at the expense of the Philippine-U.S. alliance. The biggest issue lies with the Philippine military, which has long enjoyed close ties with its U.S. counterparts and generally sees a lasting U.S. presence as critical to preventing the Chinese from subjugating the country. The original photos showing the Chinese vessels around Pag-asa are believed to have been leaked by the military. The military is less prone to political adventurism than it was in the two decades following the fall of former President Ferdinand Marcos, as half-hearted coup attempts by midlevel factions during the presidency of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo failed because of insufficient support. Absent a broad uprising that in no way appears imminent, recently surfaced rumors of a coup will prove no more substantive than those that Duterte has shrugged off since even before taking office. But amid a confluence of other political issues — corruption scandals, domestic security policies and the economy, for example – the military could play kingmaker once again. Growing criticism of Duterte’s drug war by the Catholic Church — a powerful institution in the Philippines capable of mobilizing the masses — is worth tracking in this regard.

An Uncomfortable Position

Duterte’s decision not to invoke the U.S. treaty to defend Pag-asa may seem to antagonize his own military. But as an expression of distrust in U.S. promises, it reflects another geopolitical reality: U.S. military superiority in the Western Pacific will not necessarily serve the immediate interests of its treaty allies.

Under Duterte, cooperation between the United States and the Philippines has largely continued apace, despite his scaling back of certain high-profile exercises and bombastic threats to undermine landmark military agreements. In fact, over the past few months, the United States has become noticeably more active in the country – whether by supporting the fight in Marawi, by quietly undertaking joint drills, or by increasing its security assistance. Washington recently delivered a new radar system that will give the Philippine military substantially better coverage of potential flashpoints in its maritime domain. China may be increasing its own assistance, but it still pales in comparison to the United States’.

Still, Duterte’s distrust reflects a regionwide anxiety about U.S commitments. U.S. security assistance and freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea may reassure some countries, but the U.S. has been reluctant to interfere on behalf of littoral states in territorial disputes with China. This diminishes U.S. superiority on all but a narrow set of issues in the region, leaving weaker states little choice but to refrain from provoking Beijing. For example, according to unconfirmed reports, Vietnam halted a drilling project under threat from China because it wasn’t convinced the United States would come to its aid.

For the U.S., this is a calculated choice. Washington is wary of getting pulled into a conflict it does not choose to be in. In fact, it has kept its alliance commitments to the Philippines vague to avoid such a scenario. U.S. strategy in the Western Pacific is focused on preventing the emergence of a naval power that can challenge it and on maintaining the freedom of navigation through critical sea lanes. Chinese militarization of the South China Sea does not change the balance of power or automatically dampen U.S. power projection. The fate of relatively defenseless man-made islands in the South China Sea is only minimally important.

The U.S. will maneuver to keep the Philippines dependent and prevent Manila and Beijing from reaching a deal that undermines U.S. regional influence, intervening only selectively beyond that. The Chinese will continue probing the limits of its adversaries and testing the purchasing power of its largesse. This leaves Manila in the uncomfortable position of touting the benefits of promises it cannot fully believe.