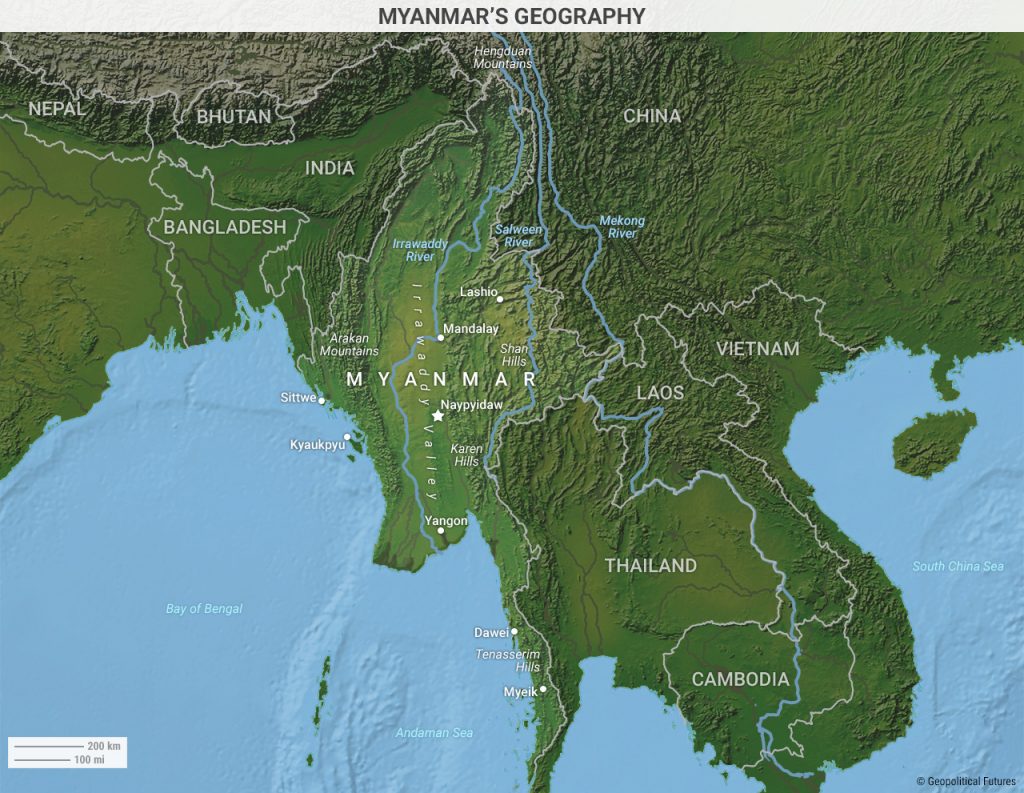

The most direct route to the Indian Ocean from China runs through Myanmar. Geographically, the country dominates the Bay of Bengal and is home to the Irrawaddy River, an important vein that provides arable land for Myanmar’s residents and an avenue for transporting goods to the ocean.

The river spans more than half of the country’s territory and hosts most of Myanmar’s commercial activity, the majority of its population and its three main cities: Yangon, Mandalay and Naypyidaw. The river was part of the Silk Road, China’s ancient trading network, and more recently in World War II, it formed part of the Burma Road, which brought Allied supplies from Lashio to Kunming.

Mountains form a natural buffer between the lowlands and the valley. To the west, the Arakan Mountains separate India from Myanmar. To the north, along the border with China, the mountains split into two regions. The 9,800-foot (3,000-meter) Hengduan Mountains — the source of the Salween, Irrawaddy and Mekong rivers — comprise the northern and tallest portion of the border. Farther south, these mountains slope down into a plateau called the Shan Hills, through which passage, while difficult, is possible.

From there, the mountains descend south along the Thai-Myanmar border, into the Karen Hills and then the Tenasserim Hills. This is why whoever controls the Irrawaddy valley controls the country, while the mountains, difficult as they are to govern, are a source of instability.

Given its geography, Myanmar is uniquely suited to serve China’s interests – interests that require a fairly meaningful economic partnership.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East