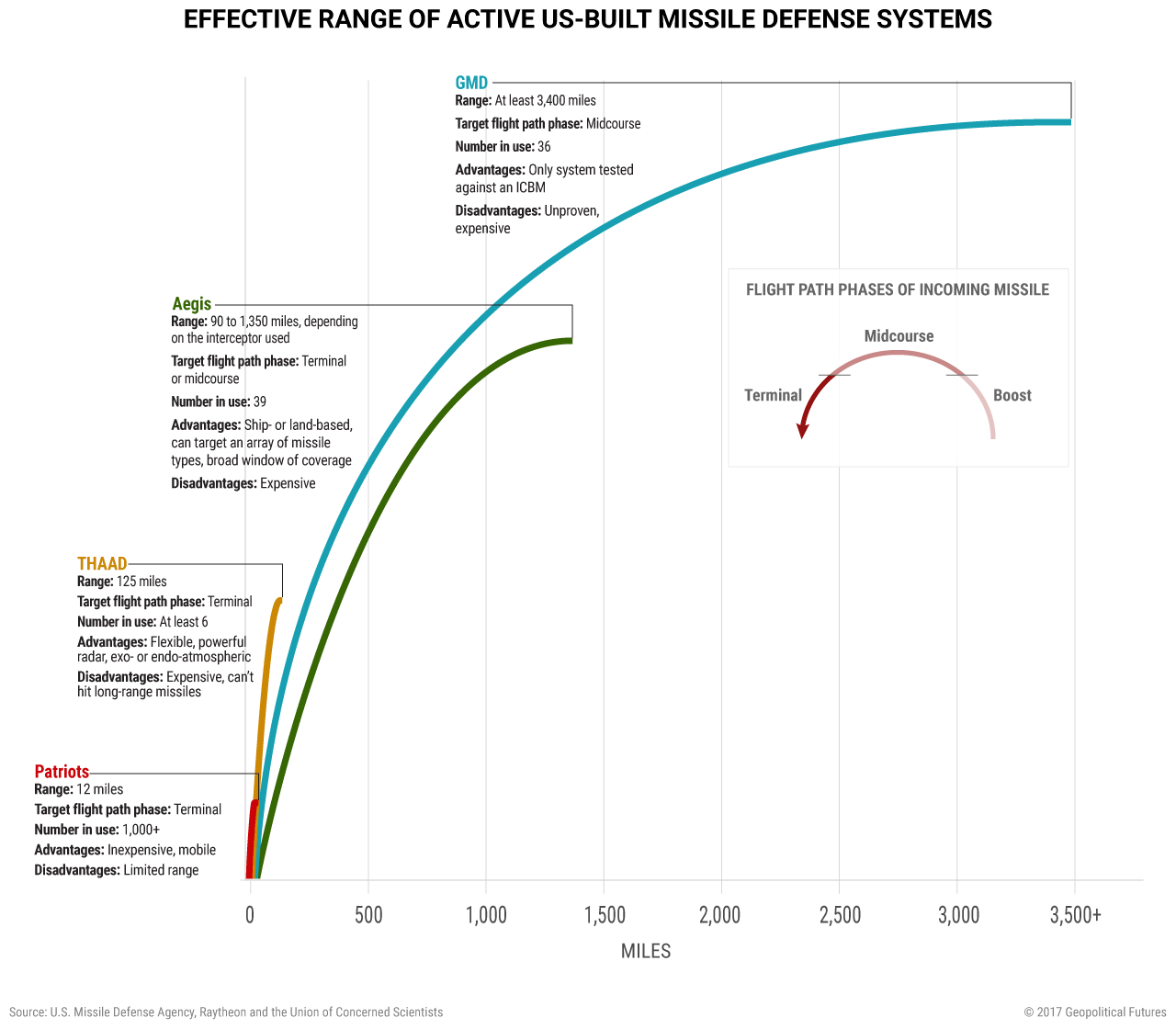

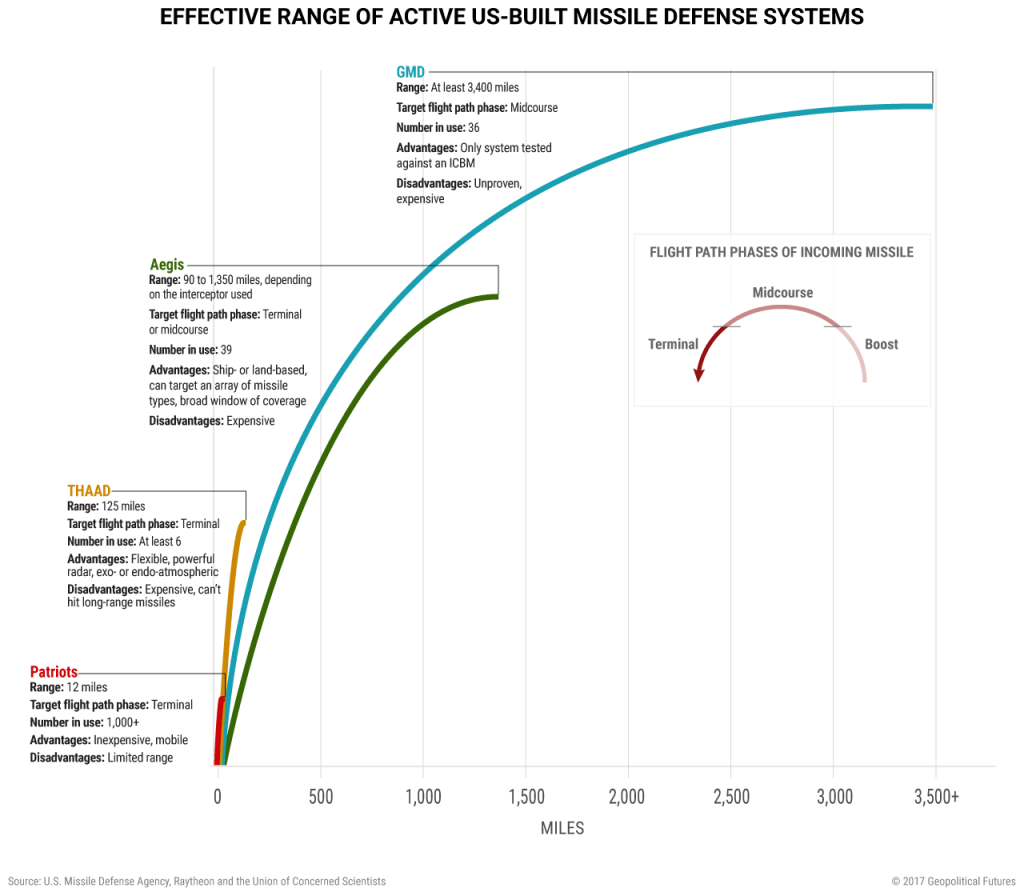

The workhorse of U.S. missile defense is the Patriot system, the only U.S. system to have been used in combat. Despite its limitations, the system would see the heaviest use, given its ability to defend against more conventional, against short-range North Korean threats launched from just across the border.

Like the Patriot system, the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense system, or THAAD, targets incoming missiles during the terminal phase using land-based batteries. In a conflict with North Korea, it would be used in tandem with the Patriots to provide two-tiered point defense against vulnerable civilian and military targets in South Korea and Guam.

The next, most flexible layer of defense is provided by the Aegis BMD system. The system is adaptable to address a broad range of threats, whether from short-, medium- or intermediate-range missiles, in either the endo-atmospheric or the exo-atmospheric stage. Most Aegis systems are deployed aboard naval cruisers and destroyers, affording the U.S. and Japan (which has six such warship-based systems) further flexibility to adapt to evolving threat environments.

The fourth, newest and perhaps most ambitious BMD layer is the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system, which has been in development only since 2003. More than any of the other systems, the long-term hope for the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system is that it will be capable of targeting longer-range missiles, including ICBMs.

BMD will not make the choice facing the U.S. any easier. Advancements in BMD could have a major effect on the battlefield and could limit the casualties in a war. But the technology is too limited, expensive, and technically and operationally unproven in combat situations to eliminate the threat posed by North Korea. And so long as there is a reasonable chance of even one nuclear warhead penetrating defenses, the strategic calculations of the U.S. and its allies will be effectively the same as if missile defense didn’t exist at all.