In Russia and Saudi Arabia, however, it’s still much cheaper to drill for conventional oil than for shale oil. Each can produce a barrel for about $10-$15. With oil priced at $50, the government in Riyadh will make more money off a single barrel than a shale oil driller will for the foreseeable future.

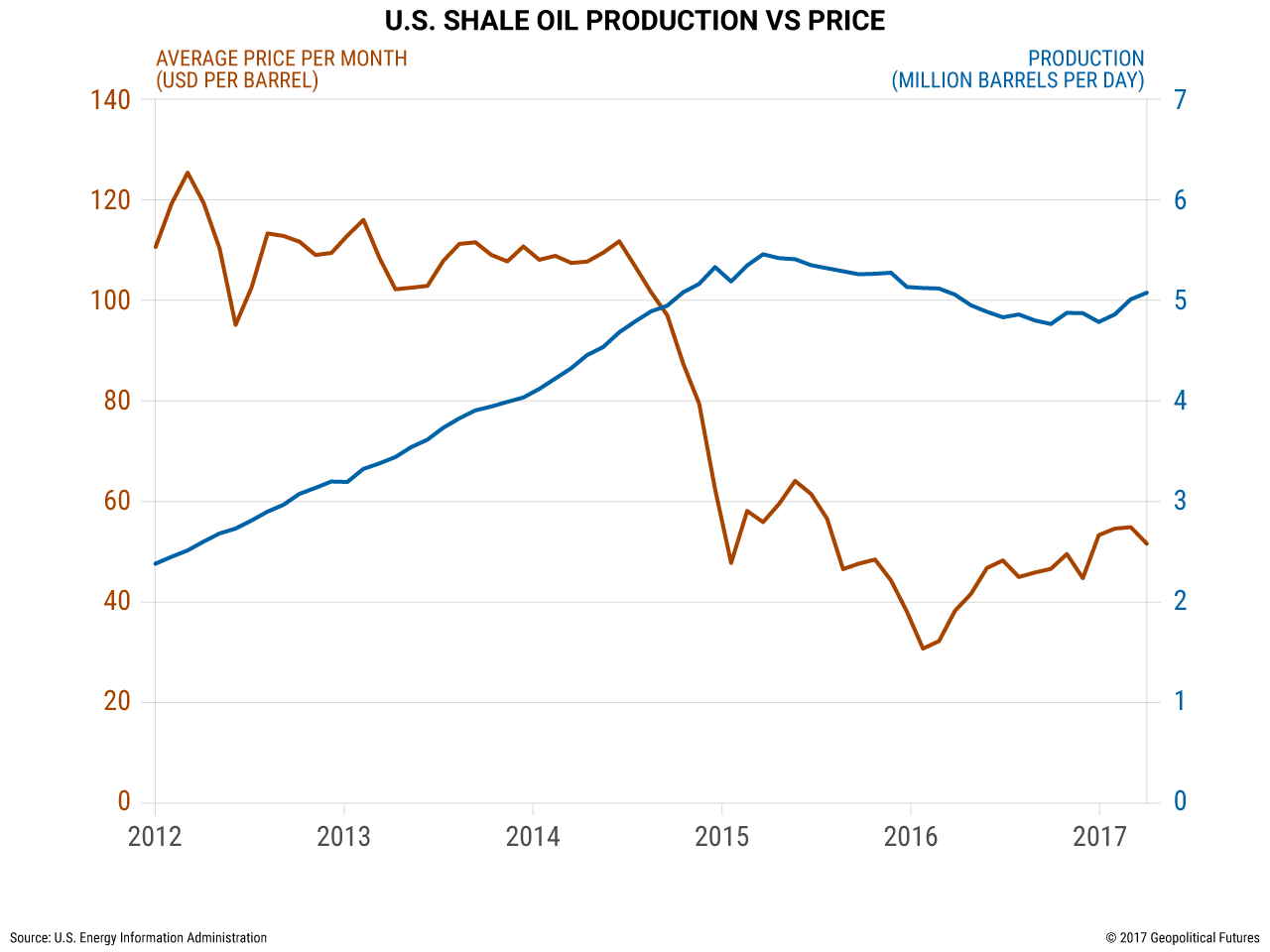

This explains why, even when prices fell so dramatically from 2014 to 2016, OPEC could afford to maintain high levels of production. Its members (and Russia) thought that if they kept prices low and captured market share, they could outlast U.S. shale producers who could, in theory, no longer afford to operate.

It was a sensible strategy at the time. The problem is it didn’t work. OPEC didn’t expect shale oil drillers to lower their costs as much as they did, nor did it anticipate how quickly they could complete unfinished projects.

A shale oil driller in the United States, moreover, doesn’t need to be more profitable than Saudi Arabia to drill new wells; the driller just needs to fetch a sufficient return on invested capital. When prices are low, drillers simply forgo exploration and concentrate on the completed wells that produce enough oil to justify their existence.