By Antonia Colibasanu

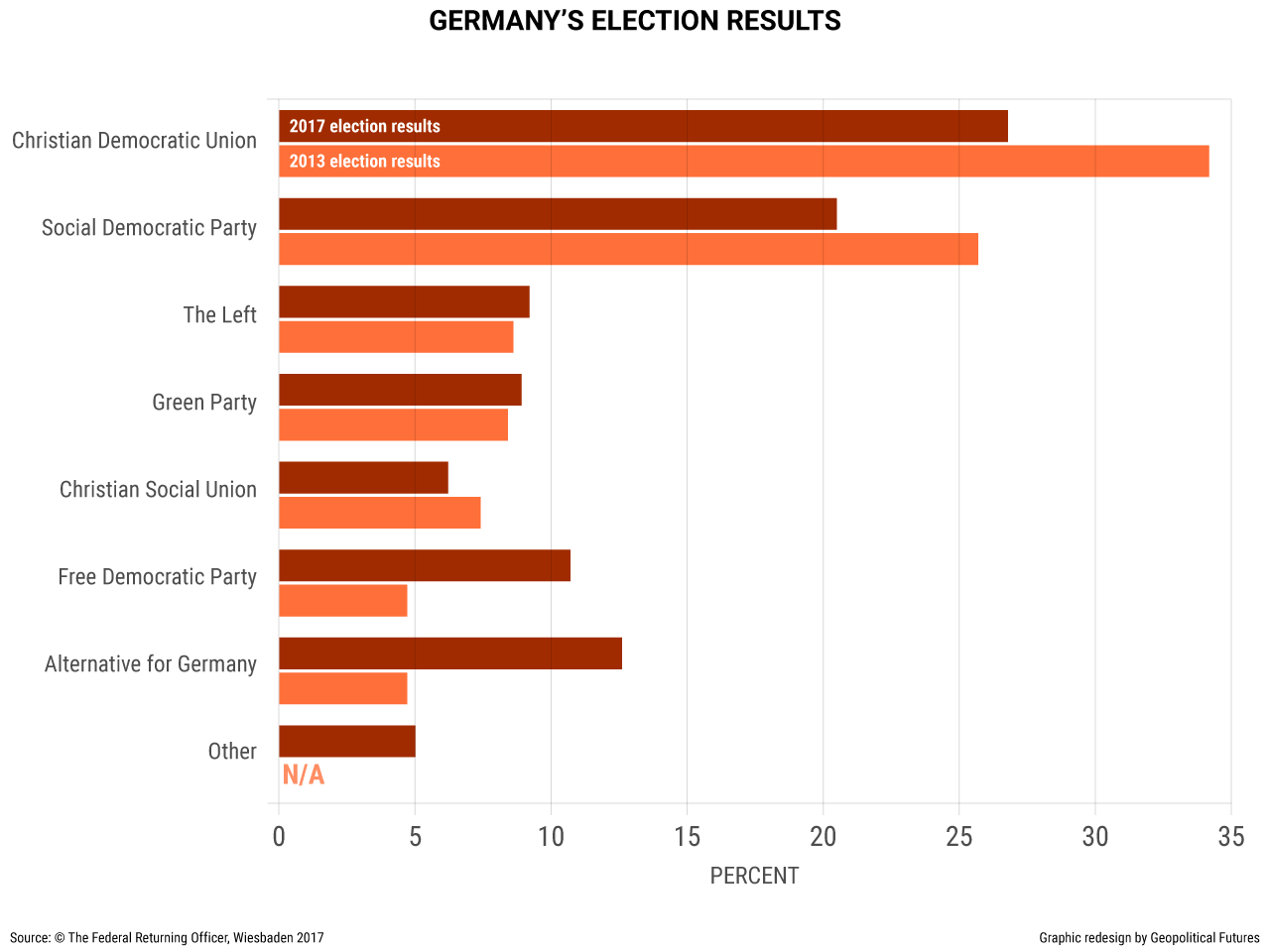

Germans headed to the polls over the weekend in an election that saw declining support for establishment parties and rising popularity of a formerly fringe nationalist party. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union experienced its worst performance since the end of World War II. Support for the Social Democratic Party fell to record lows. But the nationalist Alternative for Germany party, known as AfD, which was founded just four years ago, became the third-largest party in parliament, winning 13 percent of the vote.

Clearly, there is a shift taking place in German politics. The left’s popularity is declining throughout the country – although it is diminishing more slowly in eastern Germany – while the AfD’s support is growing. And, more important, the election results confirm that the German party system has fragmented, as divisions in German society have increased. Berlin isn’t the only European capital that has seen a nationalist party rise to become part of parliament, but considering that it is the de facto leader of the EU, we need to examine what this could mean for the rest of Europe.

Growing Dissatisfaction

The AfD is the first nationalist party since the end of World War II to enter the German parliament. In the 1960s, both conservative and communist parties were represented in parliament, but nationalism was low. Memories of World War II were still fresh in the minds of many, and most were unwilling to allow nationalist forces into mainstream politics. But dissatisfaction with mainstream parties, particularly the governing CDU and SPD, has been growing because of the country’s socio-economic problems, and it is out of this dissatisfaction that the popularity of the AfD has emerged.

Germany has the biggest economy in the European Union and dominates the bloc politically. It suffered the least from the economic crisis in 2008, but it hasn’t been immune to the problems facing other countries in the union. The German economy is largely dependent on exports, and the EU is its most important export market, so the economic struggles in other EU members will impact Germany as well. Germany hasn’t faced high unemployment rates or staggering debt, but it has seen a general slowdown in the economy. This has meant that, while it may not be reflected in official statistics, some people have lost their jobs – possibly more than once since 2008 – and others haven’t received raises. The refugee crisis only compounded this problem. Those most affected believed that the German government, just like the EU, couldn’t solve the issues that arose from the 2008 crisis. AfD took advantage of this discontent, campaigning on the idea that radical change was needed.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel gives a press conference at the headquarters of the Christian Democratic Union party in Berlin on Sept. 25, 2017, one day after general elections. ODD ANDERSEN/AFP/Getty Images

The factors that led to the rise of nationalism in Germany may be similar to those that led to the rise of nationalism in other European countries, but Germany is also a unique example because of the social divisions between the country’s east and west, which can largely be explained through its history. Reunification in the early 1990s didn’t solve the divisions between East Germany and West Germany. Both populism and nationalism have risen faster in the east than in the west, and left-wing parties have enjoyed more support in the east. The SPD has promoted a more populist agenda in the east so that it could compete with the Left Party, which tends toward communist principles. The east is still struggling to fully transition out of its communist past. Considering that the east is the poorest region in Germany and that the socio-economic problems spreading throughout Europe have affected the east more than they have affected the west, it was fertile ground for the AfD to promote its agenda.

Divided Electorate

This weekend’s election results further highlight the extent of the division in the populace, as support was split between a number of parties. The CDU and the Christian Social Union won 32.9 percent of the vote. But to form a government, they will need the support of the Green Party, which won 9.3 percent of the vote, and the conservative Free Democratic Party, which won 10.5 percent. (It is unlikely that the SPD will be willing to enter another coalition with the CDU.) The Greens and the FDP won the majority of their support in the west; the AfD and the Left Party won the majority of their support in the east. The opposition will be split between radically different parties – a weakened SPD and Left Party and a strengthening AfD – although they all find much of their support in the east, while the governing parties will more heavily represent the west. Governing will likely become difficult, and the government will need to find a balance between the priorities of the east and west.

This outcome will also make it difficult for the government to implement any reforms, both in Germany and in the EU. France, Italy and Spain have submitted proposals to increase EU investment and introduce risk-sharing measures for the eurozone – all of which will be discussed at the next meeting of the European Council. Germany has thus far played a significant role in managing EU affairs, partly because it was politically stable – the rest of the EU could trust that Merkel’s words had weight. But she is no longer backed by a large majority. This limits her power both inside and outside Germany.

The ideological composition of Merkel’s government and, more important, the increasingly nationalist opposition will influence Germany’s role in EU reform negotiations. Germany will continue to support more integration for the EU – because this will help its economy grow – but Merkel will likely become more cautious in supporting ambitious reform projects, including a common immigration policy. It is likely that euroskepticism in Germany will increase, since compromises will need to be made between the northern and the southern blocs of the eurozone. With the AfD now in parliament, reluctance to share risk with southern European members will only grow.

In addition to confirming the fragmentation of the German political system, the election results indicate a shift in Germany’s role in the EU. The German establishment can no longer ignore the popularity of nationalist parties. It will have to confront the AfD, which has reintroduced a discussion on nationalism in mainstream politics. Considering Germany’s key role in the European Union, such a confrontation will have a direct impact on how the bloc will evolve.

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President