By George Friedman

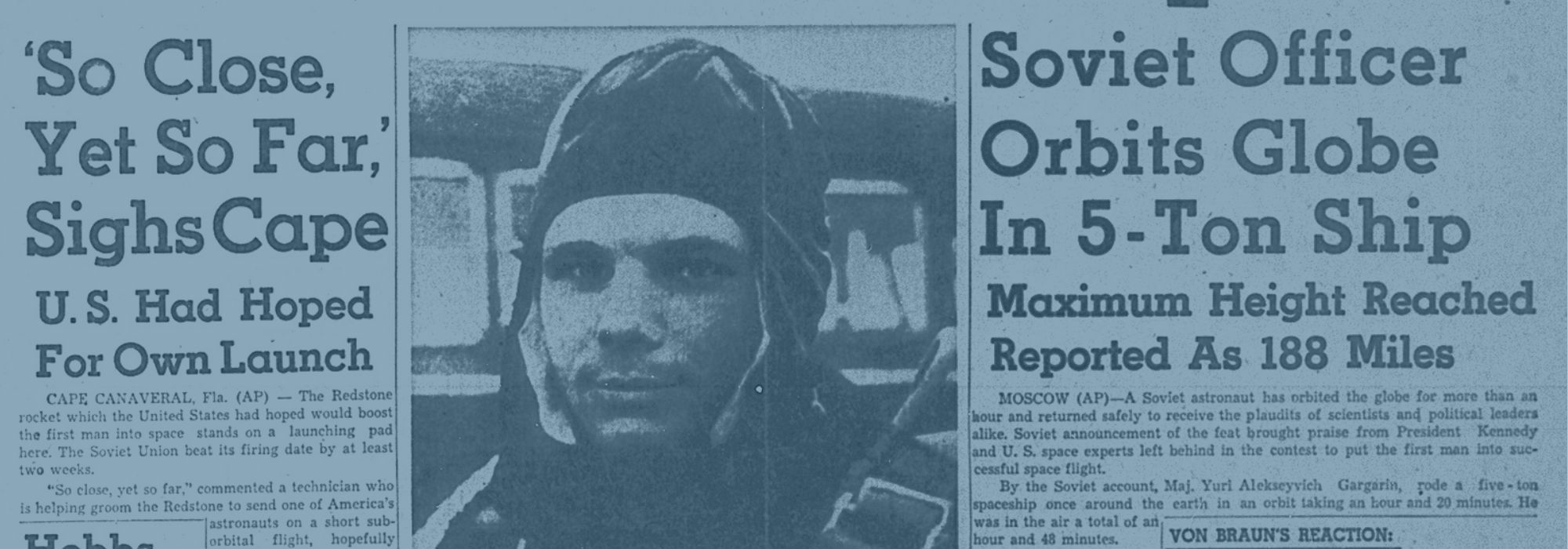

Yesterday was the 55th anniversary of the first manned space flight. The pilot was Yuri Gagarin, a citizen of the Soviet Union, and what he did helped usher in a new age. It also ushered in a profound crisis in the United States. It was a crucial moment in American manic depression.

The Gagarin flight took place deep into the Cold War, when nuclear war seemed inevitable to the public, and the United States saw itself in the midst of a race with the Soviet Union. It was far more than an arms race. It was a race of moral principles, political systems and social systems. The measure of victory was to be found in every sphere, from athletics to technology. The world understood that the United States was the master of technology. It learned that during World War II. But the Soviet Union was telling the world that it would surpass the United States not only in Olympic medals but in amazing technological achievements. It believed, not unreasonably, that such an achievement demonstrated the inadequacy of bourgeois democracy (a term I haven’t used in a long while) and the superiority of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Technology was the battleground. It created military power. It generated prosperity. But technology is not easy to understand. Gagarin’s mission was, first and foremost, understandable. The first human being to leave the earth was a Soviet citizen. Gagarin’s flight came after the Soviet launch of Sputnik, the first satellite. During the same period the United States struggled to launch a satellite, with its rockets exploding in mid-flight or on the launch pad. It is hard to remember for most, but during those years of the late 1950s there was a serious sense that the Soviets were beating the United States in the moral, political and social competition. The Soviet system had produced Yuri Gagarin and the Olympic medalists. The American system could not. Therefore, the Soviets could claim superiority.

And Americans believed it. So did much of the rest of the world. Many wished it to be true. Western European intellectuals were beguiled by Marxism. The Marxists knew in their hearts that they (and I think of Jean-Paul Sartre here) were writing moral gibberish. No one could write “Being and Nothingness” and not know he was full of it. But there was a deep “schadenfreude” toward the U.S. The world took pleasure in seeing what they thought of as American arrogance shattered by the Soviets. Much of the European elite saw the United States as crass and vulgar, an unworthy successor. This is not all of Europe by any means. Eastern Europe knew what the Soviets were, and many ordinary Europeans were grateful to the United States. But at the heart of the elite and the intelligentsia was a belief that the United States did not deserve to be where it was.

The Americans took the scorn to heart and magnified it a hundredfold. There is something in the American soul that wants to believe that it is facing disaster, that it has failed, that some corruption deep in its being will steal its success. I suspect that this has something to do with the familial recollections of immigrants. All came here because, in some way, they failed at home. All became prosperous here, but all remember how fleeting success is. This goes back to the English who immigrated before the founding. They all left England for a reason. They lived good lives here, but never forgot how England expelled them. The self-loathing mixes with genuine arrogance (this is the manic depression I mentioned earlier) and makes an American unfathomable to a European, and hard to take.

The Americans sought an explanation for being surpassed by the Soviets, and they decided it was the educational system, particularly the failure to teach math and science. America is a meritocracy, and in a meritocracy education is everything. Therefore, whenever something goes wrong, the root cause must be in how Americans educate their children. The Soviets got into space before them. The villain must be the fourth grade teacher. There was a massive transformation of education, which naturally changed nothing.

In due course, Dwight Eisenhower left office. He had not taken Soviet space stunts seriously. He was a prosaic man. He knew the Soviets did not yet have functional intercontinental ballistic missiles. He knew he had B-52s galore and intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Europe. He knew the Soviets had achieved little. But then he was a soldier and didn’t understand that few others looked at the world in terms of a real war. They thought of it in terms of a symbolic war.

John F. Kennedy understood that. Whatever his limits, he understood what Eisenhower did not. The United States had a fragile ego, and the Soviets had bruised it. Something had to be done that would be extraordinary. This had to be a speech, but a speech so startling that it would mobilize Americans as World War II had. Americans had to recover their pride and wrench admiration out of the rest of the world. Kennedy announced that the United States was going to the moon.

That was truly extraordinary. Where the Soviets had reached their limits with suborbital flight, they forced the United States, out of shame of being surpassed, into doing the impossible. I remember Neil Armstrong stepping out of the lunar lander. I remember that this was at a time when war was raging in Vietnam, and it was becoming clear that the United States was not going to win. It was a time when going to the moon had encountered the next American failure, Vietnam.

With the world condemning America for imperialism, and Americans claiming that the United States was brutal, violent and in Vietnam to make money for the military-industrial complex, the flight to the moon seemed passé. I was in college at the time, students were choosing to oppose the war by not taking finals. I was thinking that while some young people in the world go into the mountains to fight as guerrillas, Americans show their rage by refusing to do something they hate doing anyway. I was still a stranger in a strange land and I found it hilarious. I still do.

Gagarin reminds me of the Cold War. It reminds me of how seriously the Americans took it. It reminds me of how fragile American confidence is. And I remember how Gagarin’s flight culminated in Armstrong’s words, and those words were uttered at a time when the sense of failure and permanent decline was present. When we look back on the darkness that gripped the United States, we are surprised Americans could lack perspective so completely. But I am also reminded that it was this grim sense of the imminence of catastrophe and loss that powered the United States to the moon and ultimately was washed away by the fall of the Soviet Union. The United States won. And in due course the darkness returned, along with the sense of failure and inadequacy.

This is something that Europeans don’t understand about America. They see American arrogance. They do not see the self-doubt. When a presidential candidate says that the United States is a disaster, they don’t see this as an old and tired tale. They take it as the truth. Part of it is that Europeans simply don’t understand the United States. Part of it is that they want to believe it. So I return to where I was born, with my adopted country proclaiming the imminence of disaster once again. And the continent of my birth is not taking its usual pleasure, only because it really is facing disaster once again.

In all of this, I value Yuri Gagarin. He taught us what was possible, and he also taught us that earthshaking events are rare. This event also began to teach me how fragile we Americans are, how easily we fall into despair and then swing into acts of hubris that ought to cause the gods to destroy us, but never do. And now many readers will say, this time it’s different – this time we will be destroyed. Perhaps. But I’m going to Europe where destruction is far more commonplace. Remember that Gagarin flew for the Soviet Union, and the Soviet Union no longer exists.