By Xander Snyder and Cheyenne Ligon

In his recent trip to the Pacific, U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis reaffirmed the United States’ commitment to guard Japan against foreign threats: “I made clear that our long-standing policy on the Senkaku Islands stands – the U.S. will continue to recognize Japanese administration of the islands, and as such, Article 5 of the U.S.-Japan security treaty applies.” Both the United States and Japan have interests in the South China Sea. This is a shared interest – and an increasingly important one – that ties the two countries together. However, overlapping interests are not the same as identical interests, and while the United States and Japan both want to protect sea lanes in the Pacific, the motivations driving each country’s national strategy differ. Japan’s greater dependency on imports that must be transported across sea lanes and its proximity to China, which could develop the capability to block them, makes events in the South China Sea a greater threat for Japan than for the United States.

While China’s progressively aggressive posturing in the South China Sea is primarily designed for domestic consumption – by stirring up national pride to legitimize the regime – Japan nevertheless perceives these moves as serious threats. Japan must import nearly all the oil and raw materials it requires to function both economically and militarily. Japan is an island nation and must have all of its imports transported via maritime trade routes. Thus, it is imperative for Japan’s survival to maintain open, unfettered access to critical shipping lanes in the South China Sea. The United States is currently the dominant naval power in the Pacific and grants Japan, its ally, freedom of movement in South China Sea. The current arrangement works for Japan, but it means that Japan is dependent on its relationship with the U.S. to import required materials.

An aerial photo taken on Jan. 2, 2017 shows a Chinese navy formation, including the aircraft carrier Liaoning, center, during military drills in the South China Sea. STR/AFP/Getty Images

Oil is one of Japan’s greatest vulnerabilities. According to a study by British Petroleum, Japan consumes an average of 4.15 million barrels of oil per day. It has an estimated 500-600 million barrels in strategic reserves. This is further bolstered by an agreement with South Korea to share oil reserves in an emergency. South Korea’s oil reserves of approximately 81 million barrels would give Japan extra time in a potential blockade or war. On its own, Japan only has enough oil in reserve to last for about four months. In a best-case – but highly unlikely – scenario, if South Korea were to give Japan all of its oil, it would only provide Japan an additional three weeks’ worth of reserves. However, in such an emergency it is unlikely that South Korea would be willing or able to grant Japan access to all of its oil reserves. This makes Japan hyper-vigilant toward any Chinese threat to block sea lanes. Cutting off oil from Japan is an existential threat, the same one that drew Japan into the Pacific war with the United States.

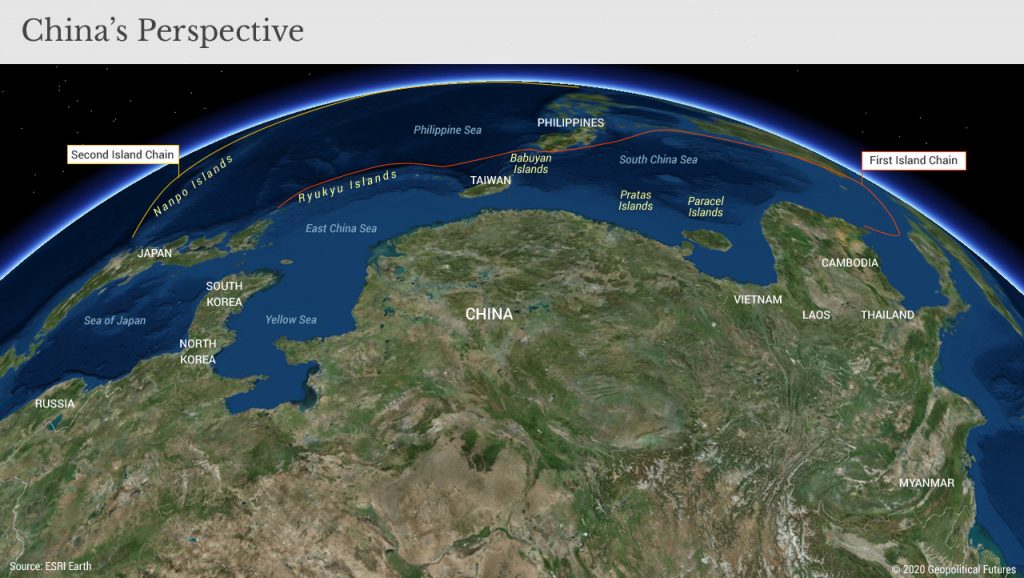

On the other hand, the United States’ primary concern in the Pacific is preventing the rise of a single state that could upset regional order and establish regional hegemony to challenge U.S. naval supremacy. Currently, China has the largest economy and is pouring money into increasing its military capabilities, which makes it the greatest threat to the existing regional equilibrium. While this distribution of power is constantly in flux, China today remains the power that the United States must balance. The U.S. has guaranteed the defense of Pacific countries including Japan, the Philippines and Taiwan since World War II and is using this interwoven web of alliances to balance China’s challenge. The United States is preoccupied with its allies’ defense not because of any moral benevolence but because those countries play a critical role in its grand strategy for balance of power.

A credible U.S. guarantee means the United States must actually intervene if China were to cross a red line, thus changing its strategy from one of deterrence to forceful ejection. There are two clear red lines China could not cross without provoking a U.S. military response. One would be any sort of offensive against Taiwan. The Senkaku Islands is the other. President Barack Obama’s administration made clear that any assault on those islands would be considered an offensive against Japanese sovereign territory, and Mattis reaffirmed that current U.S. policy considers the Senkakus to be covered under the U.S.-Japan mutual defense agreement.

Understanding Japanese fears requires understanding China’s own motivations in the South China Sea. China also needs access to maritime trade routes. Unlike Japan, however, China is more concerned with its ability to export goods than its ability to import them. China is afraid of being boxed in by the United States and its regional allies, including Japan and the strategically important Philippines, which could use their positions in the Pacific to block China’s access to sea lanes. This mentality encourages its offensive posturing. By building artificial islands in the Pacific, China is trying to secure additional territory to increase its area denial capabilities, making any potential attack more difficult. China’s regional interests place it in direct conflict with those of Japan. China is not currently ready for a real fight with either Japan or the United States, but its threats are felt more acutely by its nearby neighbor than by the U.S.

Mattis’ recent remarks do indicate U.S. concern about Chinese aggression and territorial claims in the South China Sea, but the U.S.’ preoccupation is more for Japan and other regional allies than for the protection of its own economic or military interests. Mattis’ remarks show what the U.S. would view as a red line for Chinese activity in the Pacific. Japan would prefer that the U.S. enforce this line on all Chinese activity in this region. From the U.S. perspective, however, China’s pursuit of the islands and activity in the region thus far are not serious enough threats for the U.S. to respond with anything but posturing. China does not have an interest in provoking a war, but Japan must base its national defense strategy on what is possible even if unlikely. And since this dynamic has defined the geopolitics of the Asia-Pacific region for over a century, it is important to be precise about both U.S.-Japanese shared interests as well as the gaps between them.