Initially, the protests seemed to be focused on economic concerns, namely, the sharp increase in prices of two food staples: poultry and eggs. While inflation rates have declined in Iran over the past five years, from roughly 45 percent to 10 percent, a rapid decline in poultry supplies due to the culling of more than 15 million birds over avian flu fears and an increase in the cost of imported feed led to a 40 percent increase in the price of poultry and eggs.

But within days of the initial protests, the demonstrations turned political, with protesters chanting anti-regime slogans such as “death to Khamenei,” “the Khamenei’s regime is illegitimate” and “free political prisoners.” President Hassan Rouhani delivered a speech acknowledging people’s grievances but stating that “violence and damage to public property” would not be tolerated. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of Iran, also gave a rare speech, accusing outsiders of instigating the uprising.

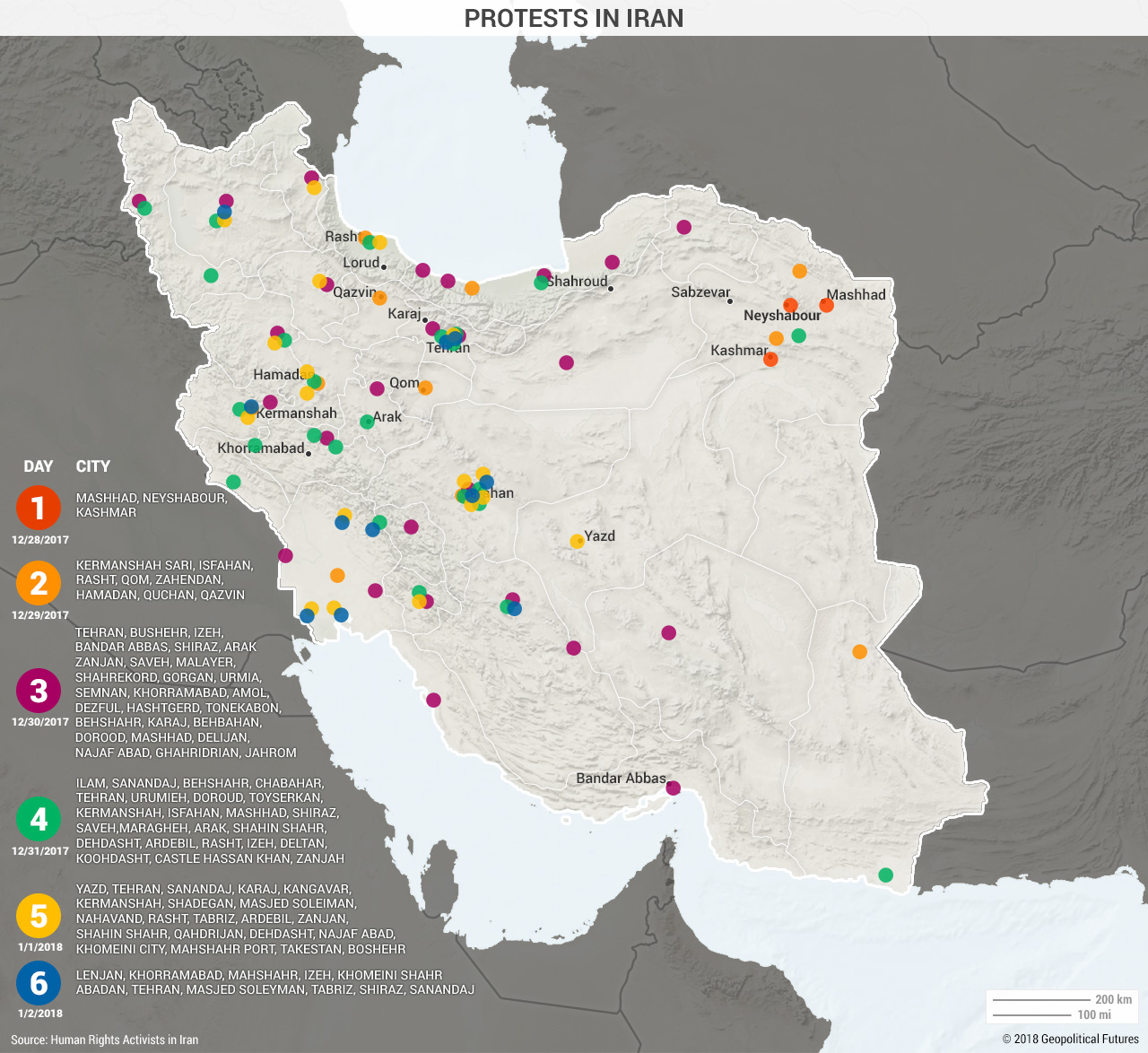

At first, the government was hesitant to respond with force to protests over food prices. But as the protests continued, police began to crack down. Estimates on the number of protesters at each rally range from 100 to thousands, while nationwide the demonstrations drew tens of thousands. Gen. Mohammad Ali Jafari, commander of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard, said that by Jan. 3, approximately 15,000 people participated across the country. This figure does not include the pro-government protests organized by the regime that took place at the same time. The government has claimed that 22 people were killed in the protests nationwide, while the opposition claims that 50 people died.

The protests had some observers questioning whether the regime was facing a serious threat. But the country has withstood large-scale protests before. In 2009, the election race between ultraconservative President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and reformist former Prime Minister Mir Hossein Mousavi generated Iran’s highest-ever voter turnout. And when it was announced that Ahmadinejad had been re-elected with more than 60 percent of the vote, the protests that followed were Iran’s largest and longest since the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

In 1999, the shutdown of a reformist newspaper by a hard-line court triggered a week of mass protests in Tehran and other university cities by supporters of reformist President Mohammad Khatami, most of them students and underemployed urban youths. An estimated 1,500 demonstrators were arrested, as many as 17 were killed, and thousands more were injured. When put in the context, therefore, the recent protests are not unprecedented.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East