By George Friedman

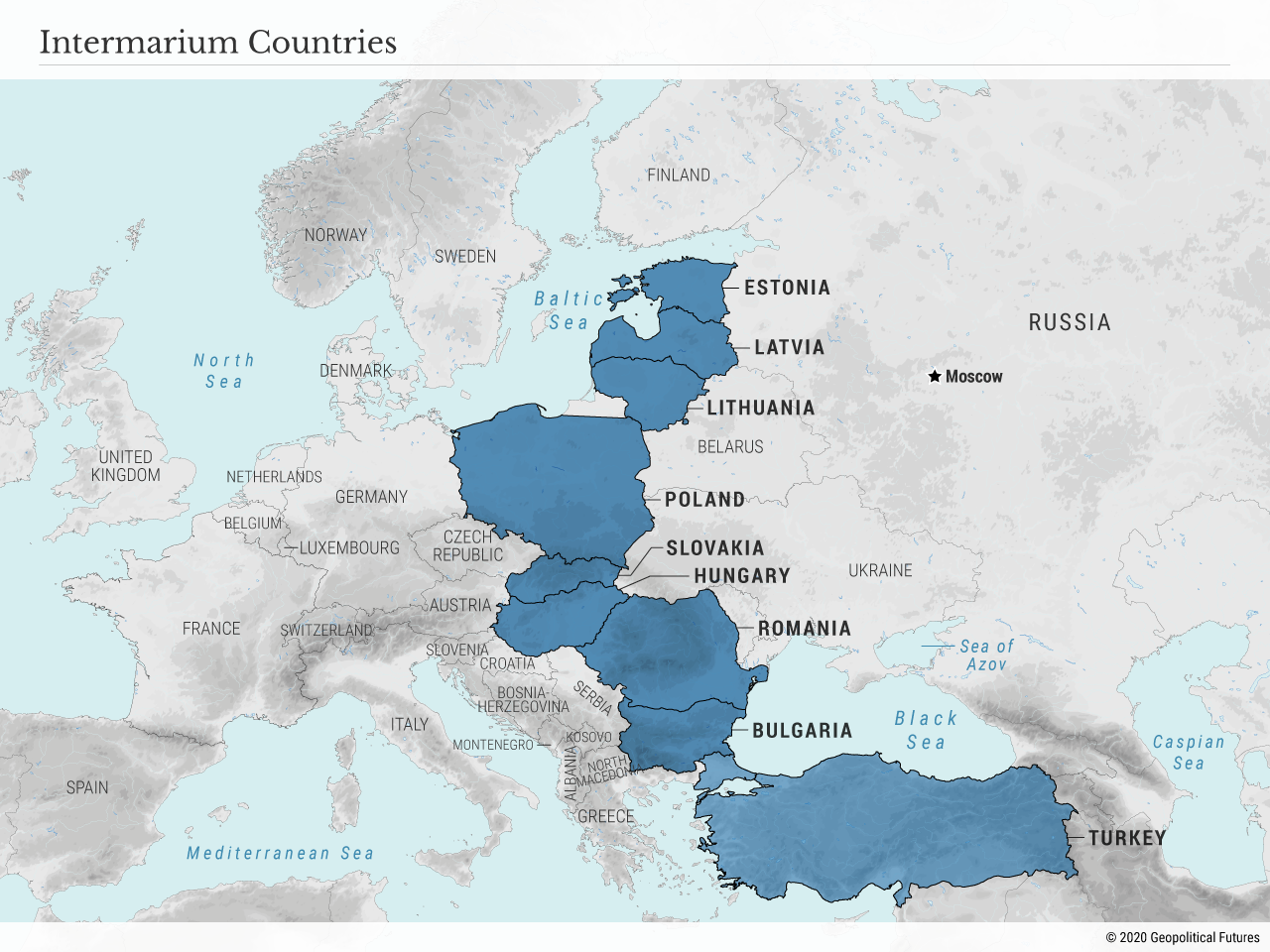

The Intermarium is a concept – really, an eventuality – that I have spoken about for nearly a decade. I predicted it would rise after Russia inevitably re-emerged as a major regional power. Which makes sense, considering it would comprise the former Soviet satellites of Eastern Europe: the Baltic states, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and possibly Bulgaria. Its purpose would be to contain any potential Russian move to the west. The United States would support it. The rest of Europe would agonize over it. What was once inevitable may soon be here.

Challenges, Intentional or Otherwise

The two foundations of the Intermarium (now frequently referred to as such in the region) are Poland and Romania, which have developed close military ties. The Baltics are already involved. The major holdout, unsurprisingly, has been Hungary, which has had to court Russia and the United States at the same time. But there are strong signals that Hungary is prepared to join. The government recently announced that it would join a Black Sea military exercise with Romania and Bulgaria – an annual exercise in which Hungary has never before participated. If this happens, then an eastern flank of the European Peninsula will have a cohesive group, backed by the global power, forming a line of demarcation between Russia and the rest of Europe.

Some are understandably worried about its formation. Few in Europe want to revert to Cold War politics; most Europeans believe they can accommodate Russian interests without creating a new containment line. U.S. sponsorship, moreover, directly challenges one of Europe’s most defining institutions, NATO. The Intermarium is not formally outside of NATO, but functionally it is, since NATO can’t really provide military assistance without U.S. help. In a military alliance, those with militaries tend to carry more weight than those without.

It also challenges the European Union, albeit unintentionally. Most the Intermarium’s members are outside the eurozone but constitute the most economically dynamic part of Europe. Eastern Europe’s economies are growing, and they boast extremely well educated, highly skilled and relatively cheap laborers. The region challenges the economic status quo, represented by the hegemony of the 1950s-style corporations that dominate European economics. As NATO showed, military alliances employ the logic of economic cooperation. The Intermarium sets the stage, in my view, of a more integrated economic drive. It will be in the EU, but it will behave differently from the EU – more entrepreneurial, more closely resembling the United States. This will create stress in the EU, which does not need any more stress.

It will also necessitate political evolutions outside the EU’s ideology. The governments in Poland and Hungary are anathema to the multilateral, collectivistic framework of the EU, and Brussels has criticized them accordingly. But neither Warsaw nor Budapest has given in to EU demands. The Intermarium therefore is more than a military alliance.

Map vs. Geopolitics

That the Intermarium has only recently begun to coalesce hasn’t stopped it from conceptually expanding. The bloc runs from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, but its logical extension goes southwest to the Adriatic Sea. The so-called Three Seas model would add Austria, Slovenia and Croatia to the Intermarium’s ranks. (And the Three Seas summit is taking place in Poland at the same time as a visit by Donald Trump. He has not rejected the idea of the Intermarium.)

The extension is explained in part by the growth of Turkey. There is no question that Turkey will become a major regional power. When it has been powerful in the past, its influence has reached the Balkans and, in more extreme cases, to Budapest and Vienna. The countries of Eastern Europe are particularly concerned with immigration, an issue that Turkey naturally abuts. But Turkish power is a deeper concern, and if Ankara realizes its potential, the Intermarium will have to block not just Russia but Turkey too.

The extension is also explained by nostalgia for the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a significant multinational success that united small countries and largely gave them a degree of autonomy. Many believe the EU, which proved incapable of managing Europe after the 2008 crisis, encroaches on national self-determination just as much as the empire did. By expanding to Austria, Croatia and Slovenia, the old empire is recreated, if only in a geographic sense.

The Intermarium is just an idea, a vehicle for regional cooperation. It is not an alliance, at least not right now. But as conceived it is meant to evolve, and its evolution creates some problems. Multinational institutions are difficult to create. They require time, money and political will, and rarely do members have the same of any of these as the others.

Another problem is timing. Russia is a threat now, albeit a mild one, considering the state of the Russian economy. Turkey, meanwhile, is not a threat at all. Once it becomes a regional power it will project its power into the Balkans, but that’s a long way off. Sequence is important, and the Three Seas expansion is a little premature.

Last, the inclusion of Balkan countries changes the Intermarium’s complexion. Adding Slovenia and Croatia will alarm the Balkan Peninsula’s largest power, Serbia, historically a dangerous thing to do. (Croatia and Serbia have fought many wars over the years, most recently in the 1990s.) Drawing the members of the Intermarium into Balkan conflicts creates a drain on resources and a potential loss of popular support. The bloc may separate Turkey from the rest of Europe, but it also encourages Serbia, already close to Russia, to pull closer to Turkey. The geopolitics and the map work against each other. If this expansion is to take place, and in due course it likely will, then Serbia must be brought into the fold. Otherwise, the danger of Turkey is enhanced, not mitigated. Even then, we should remember that Serbia did not get along with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and if the Intermarium bears its likeness, it could create problems down the road. (It’s also worth noting that Austria’s comparative affluence changes the dynamics too.)

One of the failures of the EU was its casual expansion without careful consideration of how new countries could work with older members in times of economic duress. The impulse to expand has been one of the EU’s greatest mistakes. Expansion is fine, but history shows that it has to be systematic and thoughtful. Disciplining intentions is the hardest of things.