By Allison Fedirka

In Central America, organized crime, street violence and civil unrest are nothing new. The most recent example of civil unrest comes from Honduras, where demonstrators have been protesting the president’s controversial re-election in November after a court approved changes to the constitution to allow presidents to run for a second term.

The area known as the Northern Triangle – consisting of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador – has been particularly marred by instability and violent crime, leading many to flee to the United States. In response, the U.S. is tightening immigration and border controls. This week, U.S. officials said 200,000 Salvadorans who had been allowed to come to the U.S. legally would have to leave the country. The program that allowed citizens from other Central American countries to also live in the U.S. is now under review because the administration claims it has been subject to abuse. Thus, security issues in the countries of the Northern Triangle are no longer mainly domestic problems; they are impacting the U.S. as well and its relationship with Mexico, a gateway to the U.S. for many Central American immigrants, increasingly making the violence and instability there a geopolitical issue.

Central America is linked to the international system largely through its ties to the United States, the world’s only super power, and Mexico, an emerging power. The region is composed of seven countries (Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama) that cover 202,230 square miles (523,770 square kilometers) with a total population of about 48 million. The combined gross domestic product of these countries in 2016 was $244.67 billion, roughly equal to Chile’s total GDP and just under a quarter of Mexico’s. The region is a narrow strip of land between North America and South America bounded by seas on either side. Due to their small size, isolation from the rest of the world and low incomes, Central American countries project very little power.

Nevertheless, the region played an active role in international affairs during a couple of points in modern history. Since issuing the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, the United States sought to keep foreign powers out of the Americas and to grow its regional influence. The U.S., however, was in no position to expand its power into this area until after the Spanish-American War, which the U.S. won. At that point, Spain no longer controlled Cuba, the Greater Republic of Central America had dissolved into individual countries and Mexico found itself still writhing from internal turmoil. The U.S. seized the opportunity to expand its influence in the Western Hemisphere using policies consistent with the Roosevelt Corollary, an extension of the Monroe Doctrine, including establishing business ties and military intervention. Washington’s hold over Central America in the early part of the 20th century marked its rise as the dominant power in North America.

Central America also played an important role in the proxy battle between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The region proved particularly valuable for the Soviets because of its proximity to the United States. As the U.S. chipped away at Soviet influence in Eastern Europe, the Soviets did the same in Central America. As a result, the region was rife with civil wars and foreign-backed dictatorships for decades.

When the Cold War ended, Central America no longer posed a threat to the U.S., and U.S. interest in the region began to wane. The U.S. managed to maintain influence over the Americas largely uncontested, and developments there had little impact on the United States.

This is now starting to change. In the past decade, the countries of the Northern Triangle have become known for rampant street, gang and drug violence. The area has one of the highest murder rates in the world outside of designated war zones. In 2016, El Salvador had 91 homicides per 100,000 people, while Honduras had 59 and Guatemala had 23. By comparison, the United States’ homicide rate was 5 per 100,000 people.

Violence, however, cannot be easily contained within borders. Many organized crime groups that have roots in the violence in Central America also operate throughout North America. MS13, for example, is a notorious gang founded by Salvadoran immigrants in Los Angeles, and it’s now active in many parts of Central America and the United States. Drugs from South America also find their way to U.S. markets through conflict-prone countries in Central America. Displaced by the violence, people have been fleeing the region in record numbers, and the United States is their primary destination. Since 2011, El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala have been among the top source countries for legal and illegal immigration from Latin American countries to the United States. According to a Pew report released in December, the number of immigrants from these three countries to the U.S. nearly doubled from 60,000 in 2011 to 115,000 in 2014.

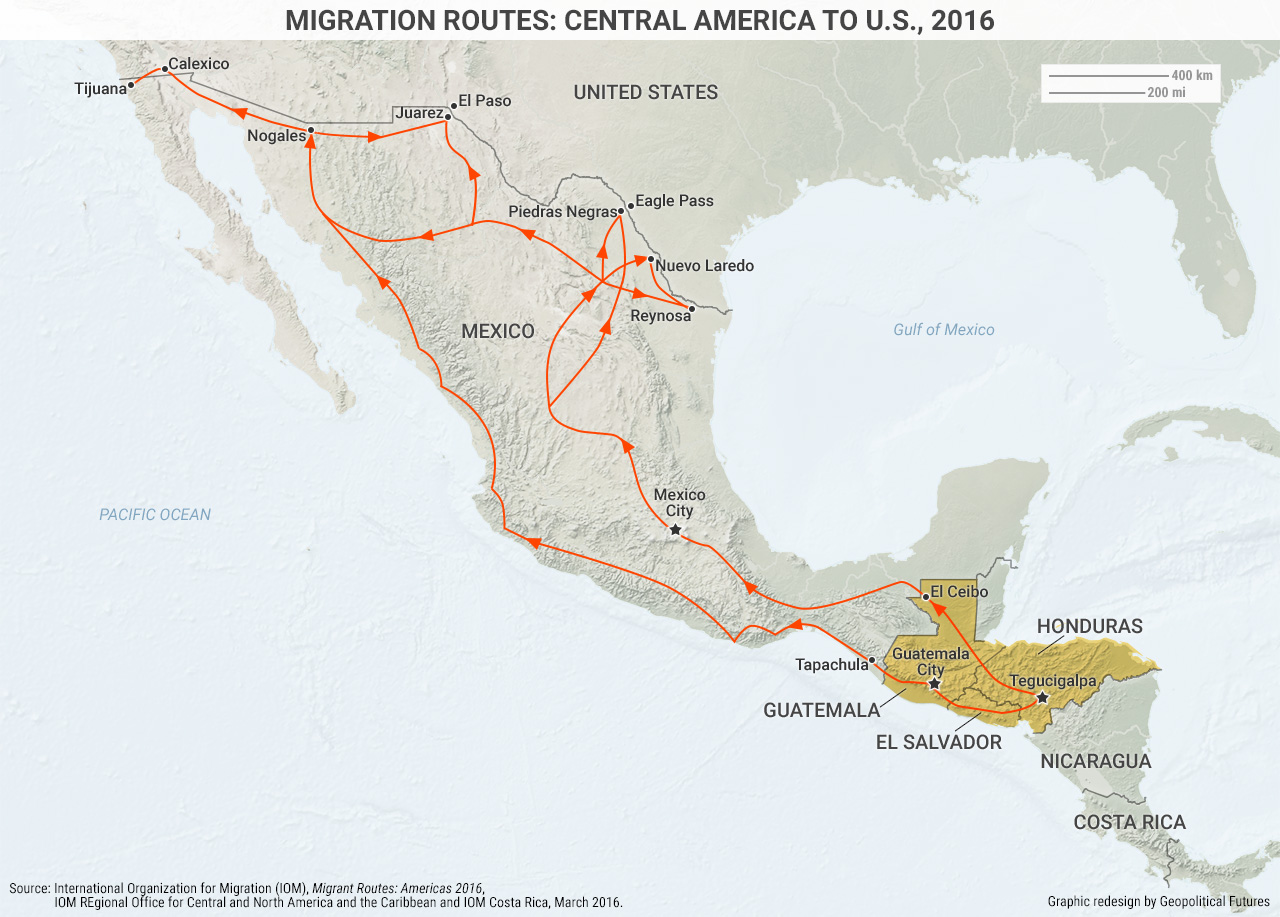

More often than not, immigrants from this region enter the U.S. illegally. As of 2015, an estimated 1.65 million of the 3 million immigrants from the Northern Triangle had entered illegally. And many arrive in the U.S. through Mexico. In fact, the majority of immigrants entering the U.S. from the Mexican border are no longer Mexicans.

As the United States imposes stricter controls on immigration and border crossing, particularly from those regions that could be seen as a security threat, it is bound to increase pressure on Mexico to tighten its own controls. The U.S. push to limit immigration includes its elimination of temporary protection status for immigrants from Central American countries – primarily Honduras and El Salvador.

The U.S. and Mexico have cooperated on border control issues for decades, as the U.S. depends on support from Mexican authorities to protect its southern border. Mexico stops 40-50 percent of the immigrants attempting to cross the border to the U.S., and both countries have worked with Northern Triangle countries to help improve local security forces and economic conditions. But in the past year or two, immigration from Central America has become a bigger issue between the U.S. and Mexico, as Washington makes it increasingly clear that its solution to the Central America immigration problem is to try to block people from crossing the border and to threaten to deport them. This in turn will place a heavier burden on Mexico to address the security issues in the Northern Triangle. Mexico may not have the resources necessary to deal with these issues now, but in time it will be forced to become more involved.

The shift in the U.S. approach to Central America, from indifference following the Cold War to intensifying interest today, makes the region more geopolitically relevant. But this relevance is derived not necessarily from developments in the region itself but from the region’s ability to impact relations between the U.S. and Mexico. The more the U.S. tries to stem Central American immigration, the more Mexico will feel the pressure to become engaged. But Mexico has its own organized crime problem to deal with and can’t spare resources on the Northern Triangle. These countries will need billions of dollars in development funding – not exactly petty cash for the Mexican government. With instability at its doorstep, Mexico will be forced to respond in some way, but its options will be limited.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East