By Xander Snyder

India’s central government is taking a bigger role in managing the country’s financial system through a new stimulus plan that will inject cash into banks and infrastructure. Because of a growing number of nonperforming loans, over the past several years, India’s banks have struggled with both profitability and capital adequacy. NPLs, however, affect not only banks but also the broader economy, since banks must withhold a certain amount of reserve funds as protection against poorly performing assets. As a result, some productive enterprises could have trouble getting access to the credit they need to support their business.

India’s new $139 billion stimulus package, announced late last month, aims to address this problem. Roughly $32.5 billion will be spent on bank recapitalization, while the rest will go toward infrastructure. The idea is to provide new capital to banks, which will let them increase lending while bolstering India’s economic growth by creating new jobs through infrastructure projects.

It’s not intended as a cure-all, but it is a step toward cleaning up bank balance sheets and claiming greater central government oversight over lending practices. It’s part of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s attempt to consolidate political power and assert greater control over the country’s economy.

Indian bank customers queue to try to withdraw money from an ATM in Imphal, the capital city of India’s northeastern state of Manipur, on Dec. 8, 2016. Tens of thousands of Indian villages will be equipped with card-swiping machines to boost cashless payments, the finance minister said Dec. 8, a month after the government banned high-value banknotes. BIJU BORO/AFP/Getty Images

Recapitalization Plan

The bank recapitalization will occur over the next two years and is intended to be “liquidity neutral,” meaning that only a small portion of the recapitalization funds will come directly from the Indian government’s budget. Of the $32.5 billion slotted for bank financing, about $2.7 billion will come from the 2017-18 budget. (The government already set aside $1.5 billion in the last budget for bank funding.)

Another $8.7 billion will come from the banks selling equity stakes. This may not seem like a bailout, but it is essentially a way of injecting cash into the banking system because many of India’s banks are publicly owned and the central government can, therefore, force them to sell equity to raise money. (Though some banks are privately owned, in part or in whole, public-sector banks account for over 70 percent of all assets in the financial system and about 80 percent of all nonperforming assets.)

The remaining $21 billion will be raised through what’s called recapitalization bonds. These government-issued bonds will have sovereign credit protection, a huge advantage when credit rating agencies inevitably scrutinize the incremental debt. The government will force banks to purchase these bonds and then will use this money – the banks’ own cash – to purchase a greater equity stake in the banks. In the end, the banks will have the same amount of cash but a number of additional government bonds. These new debt securities – assets for the banks – will act as reserves and enable banks to lend out the cash that previously had to be used as reserves.

The government doesn’t expect that $32 billion will solve all of India’s banking problems, but it has passed other reforms that will work in tandem with this recapitalization plan. In December 2016, it initiated bankruptcy reform that will let banks more easily write down bad loans and take possession of companies that have defaulted. Declaring bankruptcy was previously a far more difficult process and prevented banks from writing off loans that failed to generate a return, forcing them to hold capital in reserve against poor quality or failed assets.

Indian banks have roughly $140 billion in bad loans, substantially more than the total value of this bailout. The official NPL rate provided by the Indian government hovers at about 8 percent of all bank assets, although unofficial estimates have placed it closer to 16 percent. Fitch, a credit rating agency, estimated that roughly $90 billion would be needed to recapitalize the system and bring NPLs to a non-threatening level.

Infrastructure Stimulus

The second part of the government’s stimulus package will see $106.5 billion spent over five years on new, productive infrastructure – including 52,000 miles (84,000 kilometers) of new roads – which will help connect disparate and decentralized areas of India, tying them closer to the country’s economic hubs.

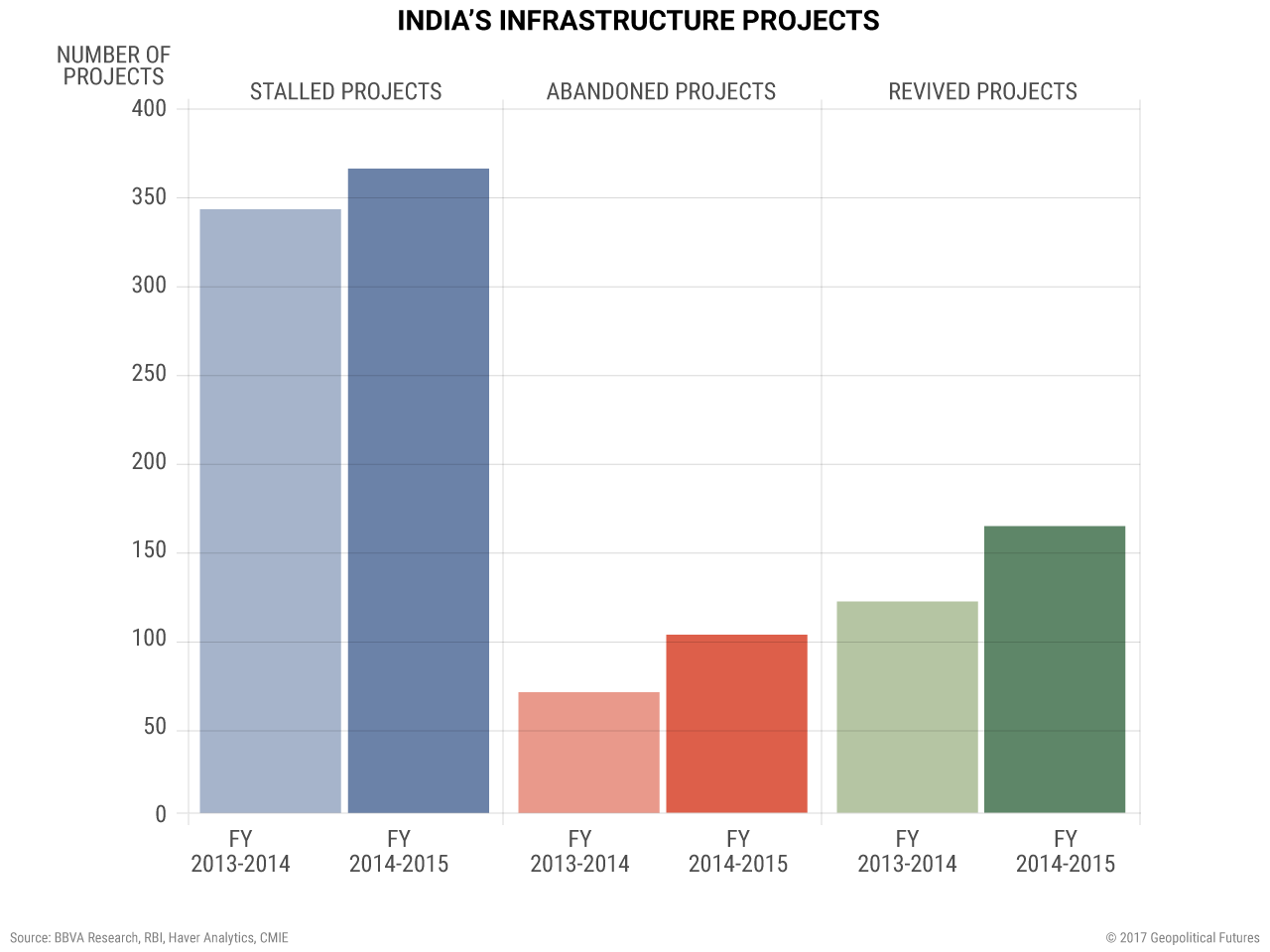

India’s poor infrastructure hinders growth in remote areas. The central government hopes this new infrastructure spending will give the economy, which has stagnated largely due to constrained credit, a much-needed boost while at the same time creating jobs that will support greater consumer spending. In theory, the new infrastructure projects would be self-supporting, generating cash flow on their own so that any loans used to fund them would be paid back and wouldn’t contribute to the NPL burden. A number of projects that were funded through the last round of credit extension, however, remain either stalled or abandoned.

Connecting the far-reaching corners of the country through better infrastructure would also give the central government an opportunity to project its power into these areas. Isolation has forced these areas to become fairly independent. In conjunction with the tax reforms it is implementing, India’s central government hopes this move will bring a greater portion of the country under its direct purview. Providing access to these areas through transportation infrastructure is key to asserting that control.

Between India’s demonetization efforts last year and this new stimulus plan, it’s clear that Modi believes he can achieve centralization through economic reforms. What is less clear is whether these measures will work, and whether he’ll be forced to conceive of even more ways to intervene in the economy to achieve his broader goals.