By George Friedman

The South China Morning Post published an article on Jan. 7 that claimed China was “in the lead” of the development of hypersonic weapons technology. The article points out an important evolution in modern warfare, one that could have a major effect on how wars are fought. It is one of the rare technical matters that are actually strategically important.

War: A Matter of Math

In laymen’s terms, a hypersonic missile is a missile that can travel extremely fast. It is what’s known as an air-breathing weapon, which differs from an intercontinental ballistic missile in that it is externally fueled. It is the descendent of early cruise missiles such as the German V-1 and the U.S. Matador. These forebears were powered by jet engines and could fly to a target (occasionally) without a pilot. Later subsonic cruise missiles could go faster, powered as they were by ramjets, which compress incoming air and mix it with fuel to increase speed.

The Tomahawk had an even more important characteristic: It was a precision-guided munition, a technology whose importance is difficult to overstate. Firearms – everything from pistols to artillery – are traditionally ballistic weapons. Once they are fired, the trajectory of their projectiles is set in stone, determined by the hand-eye coordination of the shooter, math, physics and a good deal of hope. Manned bombers also used ballistic weapons. Once a bomb was dropped, it would go where it would go.

Ballistic weapons are, unsurprisingly, inaccurate. Early in World War II, for example, the British bombed Germany. The bombs were so far off target that German intelligence could not figure out what they were bombing. The British recognized this weakness, as well as the vulnerability of the aircraft dropping the bombs, so they began to bomb at night – indiscriminately, with incendiary weapons. They accepted their inability to hit military targets and opted for the destruction of cities.

Muskets and rifles were similarly afflicted. The average soldier wielding one was unable to hit a moving target, especially when he was under fire. In the 18th century, armies compensated by placing soldiers in three lines. Each line would fire in turn, creating a barrage of bullets that would offset the inaccuracy of any one round. There was a certain logic to it; warfare is statistical. The low probability of hitting a target with ballistic weapons was improved by increasing the number of rounds fired.

And so the mathematics of war required large armies, vast industrial plants and a great deal of time. But three things changed the equation. In 1967, Egypt sank an Israeli destroyer using Soviet-made precision-guided missiles. In 1972, the United States destroyed the Thanh Hoa bridge in North Vietnam using bombs guided by television and directional controls. (The bridge was critical; many American lives were lost to bring it down.) In 1973, the Egyptians destroyed an Israeli armored brigade with AT-3 Saggers, anti-tank missiles guided by a man who looked through an eyepiece and adjusted the course of the missile as needed.

The introduction of the precision-guided munitions revolutionized tactical warfare. War ceased to be masses of men using inaccurate weapons to kill each other. Fewer men were needed to destroy enemy personnel and equipment. In fact, now that they were at greater risk of being destroyed, traditional weapons had to be upgraded. The tank was fitted with various exotic armors. The manned bomber adopted stealth technology. Carriers adopted anti-missile systems such as the Aegis. This decreased the number of platforms but sent the price of each soaring.

The Wartime Needs of the U.S. and China

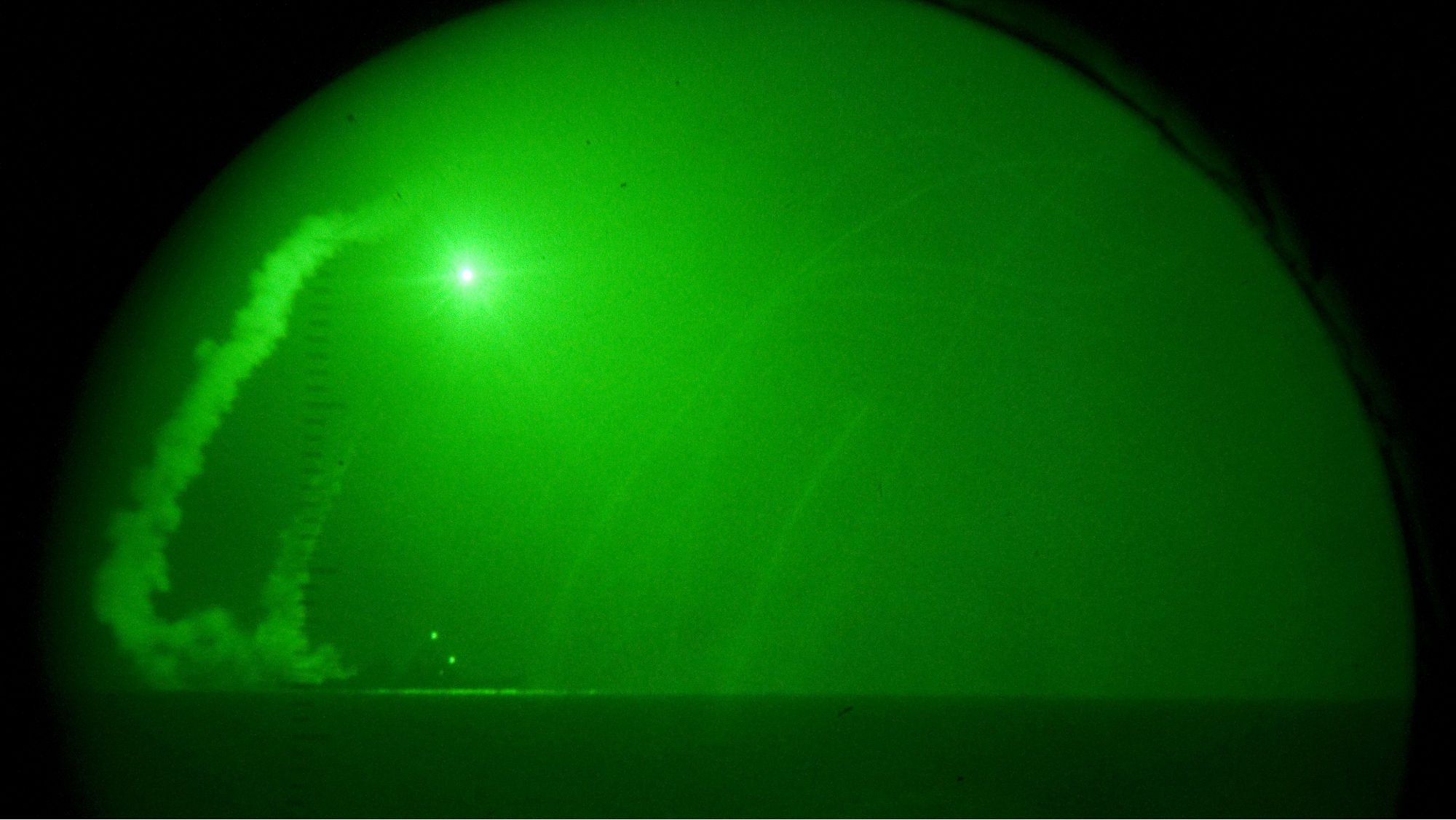

Improvements to defensive systems, in turn, led to improvements in offensive systems, which naturally became faster and deadlier. Hence, the creation of hypersonic weapons powered by what’s known as scramjet engines, which enable hypersonic missiles to travel much faster than their subsonic counterparts – more than 4-5 times the speed of sound, in fact – and are relatively accurate. Given China’s military doctrine, which currently focuses on sea lane control, Beijing’s interest in tactical hypersonic cruise missiles makes sense. Its ship-to-ship combat capability is limited, and so it has a problem engaging tactically with an enemy naval force. What the Chinese need are relatively short-range missiles to force the U.S. Navy to retreat from the South China Sea. Precision-guided cruise missiles might be able to saturate, and then penetrate, U.S. ship defense systems. Warfare would then become a matter of intercepting high-speed missiles or destroying the platforms from which they are launched, assuming the intelligence is available.

The United States has a different strategic problem. Most of its wars are fought in the Eastern Hemisphere, where it takes months to deploy armor, aircraft, personnel and the vast supplies needed to support them. Accurate weapons that travel incredibly fast, then, are extremely attractive to the Americans. Sending thousands of tanks to fire 100-pound shells three miles is not an elegant solution to the battle problem. It takes months. The ability to deliver precision munitions to the target area at Mach 20 within a half an hour delivers the same explosive with precision and without a monthlong buildup.

Precision-guided munitions ended the era that began with tube-fired projectiles (guns, if you prefer). In their place are munitions that can maneuver to the target after they are fired, either guided by the shooter or guided autonomously by its own sensors and guidance system.

Hypersonic missiles increase the speed of precision-guided munitions dramatically. One change they introduce is tactical, making it hard to defend a target. The other change is shifting the tempo of war by eliminating some of the delays imposed by the weight and quantity of weapons and supplies.

The Chinese strategic situation requires relatively short-range hypersonic weapons to threaten the American fleet. The United States needs to defend itself from these weapons, but what it needs strategically is long-range, extremely fast hypersonics to close the window of vulnerability it faces in any war in the Eastern Hemisphere.

It is of course unclear what either country actually has. There are those who argue authoritatively of Chinese or American capabilities or lack of them. Those who know don’t talk. Those who talk don’t know. I don’t know what China or the United States is working on or has. What I do know is the geopolitical problem each country faces, and the type of weapon that might fix it. I would bet that both countries are building the weapons they need, and likely already have them.

I might add that in trying to patrol Baghdad or maintain control of Xinjiang, such weapons are of little use. The kinds of war that have been fought in recent years are very different from the wars that might require these. But the wars that will urgently require these are the wars that nations must win.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East