By Antonia Colibasanu

As tensions between the U.S. and Russia heat up, the concept of the Intermarium alliance among Eastern European states to block Russia’s expansion westward is gaining steam. Romania and Poland – both of which have strong military ties to the U.S., a major supporter of the Intermarium – have long been the pillars of this emerging alliance. Hungary has been the major holdout.

Hungary is sometimes seen as a rogue nation in Europe for its close ties to Russia, as well as its opposition to Brussels. But for years, it has courted both Moscow and Washington. It is reliant on Russian natural gas imports, but it also depends on the European Union for trade and structural funding and on NATO for security.

But the relatively cold welcome offered to Russian President Vladimir Putin on his recent visit to Budapest indicates Hungary is veering away from building closer ties to the Kremlin. The Hungarian government visibly downplayed the visit, and the leaders of the two countries opted not to hold a press conference, which is normally routine on such diplomatic trips.

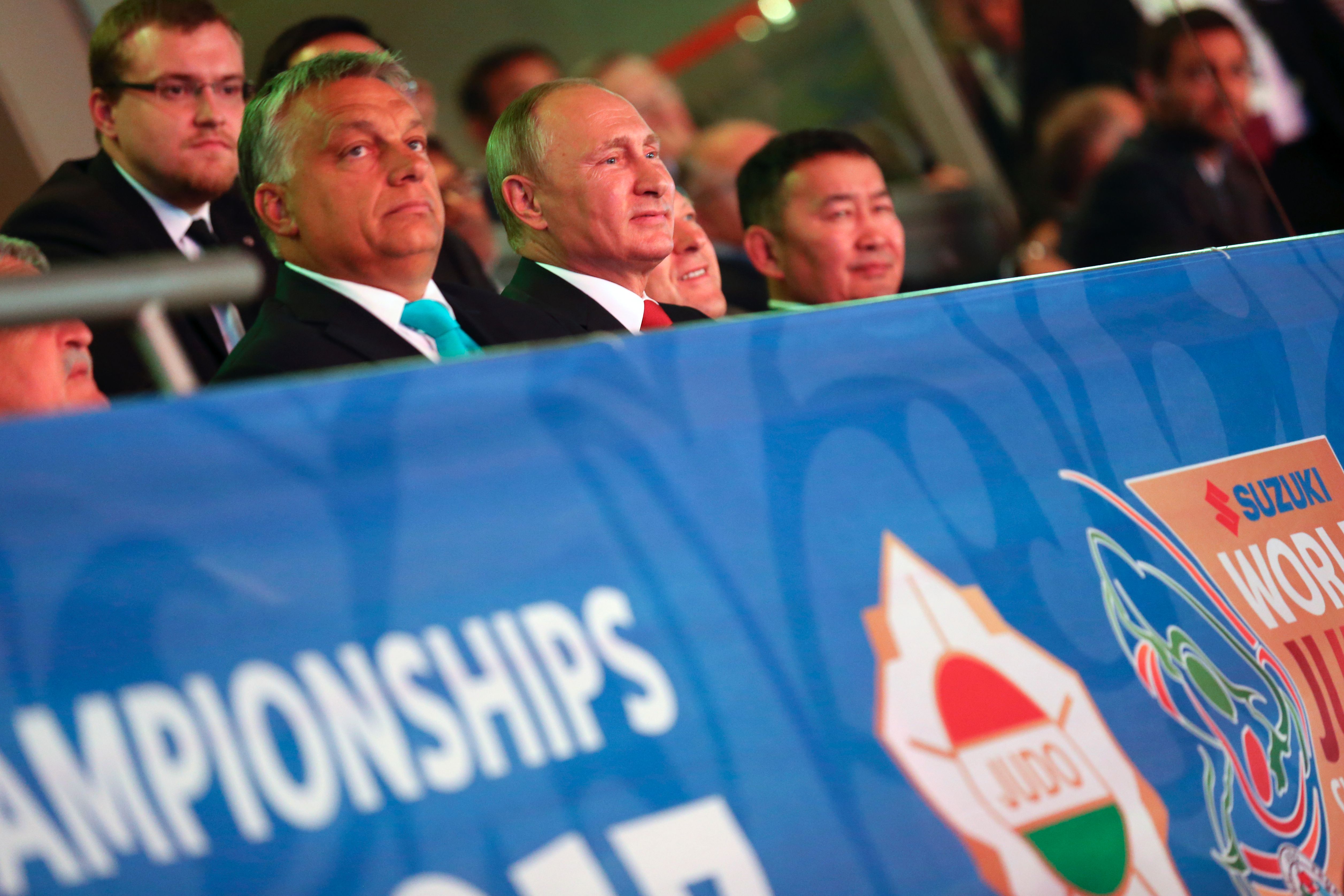

Russian President Vladimir Putin (C) sits next to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban (L) during the World Judo Championships in Budapest on Aug. 28, 2017. FERENC ISZA/AFP/Getty Images

Tense Relations

To understand Budapest’s changing approach toward Russia, we need to understand the dynamic of Hungary’s relations with the West. Hungary’s relationship with Western Europe remains tense. Differences over the EU’s refugee policy persist, and the European Commission has launched infringement procedures against Hungary over legislation perceived as cracking down on civil society organizations and foreign-run universities. Budapest also severed diplomatic relations with the Netherlands on Aug. 27, after the outgoing Dutch ambassador to Hungary compared the Hungarian government’s approach to its enemies to that of terrorists.

The biggest point of contention between Hungary and Western Europe of late has been the refugee issue. Budapest opposes the EU’s plans to relocate refugees throughout the bloc. Sixty-six percent of Hungarians side with their government, according to a Pew survey released in June. Other Eastern European countries also share Hungary’s opposition to the refugee quota system.

And so, Hungary has tried to forge closer ties with the U.S. and Eastern Europe. Along with Romania and Bulgaria, Hungary hosted the Saber Guardian U.S.-led military exercise. On Aug. 30, the Hungarian minister of foreign affairs participated for the first time in an annual meeting of the Romanian diplomatic corps. And in February, the Romanian foreign minister participated in an annual meeting of the Hungarian diplomatic corps. Romania and the U.S. have also been deepening their strategic relationship, with the Pentagon announcing it will spend up to $100 million to modernize the Kogalniceanu military base.

Setting Up a Containment Line

No one in Europe wants a return to Cold War politics, and Hungary is no exception. The Europeans believed they could accommodate Russian interests without creating a new containment line. But as events in Ukraine and elsewhere in Eastern Europe unfolded, the U.S. realized a containment line was necessary. That, essentially, is the purpose of the Intermarium.

Hungary may have previously resisted the Intermarium, but the country’s security depends on NATO – and thus on the U.S. And so it has taken small but notable steps to realign with Washington and join the Intermarium.

This doesn’t mean that relations between Hungary and its Eastern European neighbors are perfect. Last week, Hungary suspended its support for Romanian and Croatian membership in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Hungary’s opposition to these countries’ membership in the OECD, which has no strategic importance, was a gesture of support for the ethnic Hungarian communities in both countries – communities that Hungary claims have faced oppression. These populations are eligible to vote in the 2018 Hungarian elections, and the Hungarian government wanted to show its support by blocking Croatia’s and Romania’s accession in the organization.

The upcoming elections have also played a role in Hungary’s approach to Russia. Russia is seen as an alternative to the EU, and in a country with a relatively high degree of euroskepticism, Orban can’t be seen as too tough on the Kremlin. He also needs to ensure that Hungary has access to cheap energy, which Russia can provide. Orban owes his 2014 re-election to his ability to reduce energy costs for Hungarians, and he must ensure that this policy stays in place into 2018.

The Energy Factor

Even without the upcoming elections, Hungary would remain dependent on Russia for its energy needs. Hungary imports 80.6 percent of its natural gas supplies from Russia. Orban’s short-term goal is to reach a flexible and affordable energy deal with Russia.

But these supplies come with some risk. The natural gas imports from Russia are delivered through a pipeline that passes through Ukraine. The only alternative for Hungary to the current route is a pipeline that will connect Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Austria, called the BRUA pipeline, currently under development. This could help Hungary avoid a possible blockade of the existing route should the conflict in Ukraine escalate.

Russia has used its energy supplies as a powerful political tool, and it doesn’t want these supplies cut off. One way it can ensure this doesn’t happen is by increasing the amount of Russian gas kept in Hungarian storage facilities – from where Russian gas could be distributed, in the short term, to European consumers without the Ukrainian pipeline. This way, Russia can prevent its customers from seeking alternative sources of fuel. The two countries discussed increasing Russian gas storage in Hungarian facilities in July. For Hungary, this would be a tactical move. Budapest knows how important supply lines through Central and Eastern Europe are for Russia, and it will use this issue to negotiate access to low-cost natural gas.

But reliance on Russian energy is nonetheless a vulnerability for Hungary. Budapest therefore wants to increase its supply of locally produced nuclear energy. Hence its plan to upgrade the Paks nuclear plant. But even this plan relies on Russian assistance. Russia will fund the project to the tune of 10 billion euros ($12 billion), or 80 percent of the total cost, and Hungary is expected to repay the loan over 21 years. The European Commission has cleared the project, which is expected to contract local companies for 40 percent of the construction work. Orban’s government has trumpeted the project as a way to ensure Hungary’s energy security and create jobs for Hungarians.

For Russia, cultivating closer relations with Hungary has both a financial and a strategic purpose. It wants to maintain open routes to European markets and show Russians that their country is not isolated, despite the sanctions recently imposed by the United States. But for Hungary, becoming too dependent on Russia is risky – it might end up jeopardizing Budapest’s ties to Washington, a key component of the country’s security strategy. Orban won’t completely break off relations with the Kremlin, but he appears to be pulling away from its grasp.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this report misstated the percentage of the total cost of the Paks nuclear plant upgrade that Russia will fund. It is 80 percent.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East