By Jacob L. Shapiro

On Feb. 19, Chinese President Xi Jinping attended a symposium on journalism in China. In remarks to the 180 various media professionals gathered at the symposium, Xi gave a wide-ranging speech about the role that news media plays in realizing the goals of the Chinese Communist Party. Xi’s speech has run above the fold in Chinese news sources over the past week, with Xinhua News Agency and the People’s Daily newspaper each publishing positive commentaries almost every day since Xi gave his speech. Liu Qibao, head of the publicity department of the CPC, said on Feb. 24 that all media personnel should study and internalize Xi’s remarks.

The New York Times has its own evaluation of Xi’s media directives. An article published on Feb. 22 said Xi’s comments made it abundantly clear that “the Chinese news media exists to serve as a propaganda tool for the Communist Party, and it must pledge its fealty to Mr. Xi.” The New York Times is not alone in this characterization: many Western media outlets are crafting a similar narrative about the direction in which Xi is pushing Chinese journalism.

There is something inconsistent about this characterization, however. If we take Liu’s advice and study Xi’s remarks closely, we can craft a different narrative. Two moments during Xi’s speech stand out in particular. The first is when Xi said that journalism “is crucial for the Party’s path, the implementation of Party theories and policies, the development of various Party and state causes, the unity of the Party, the country, and people of all ethnic groups, as well as the future and fate of the Party and the country.”

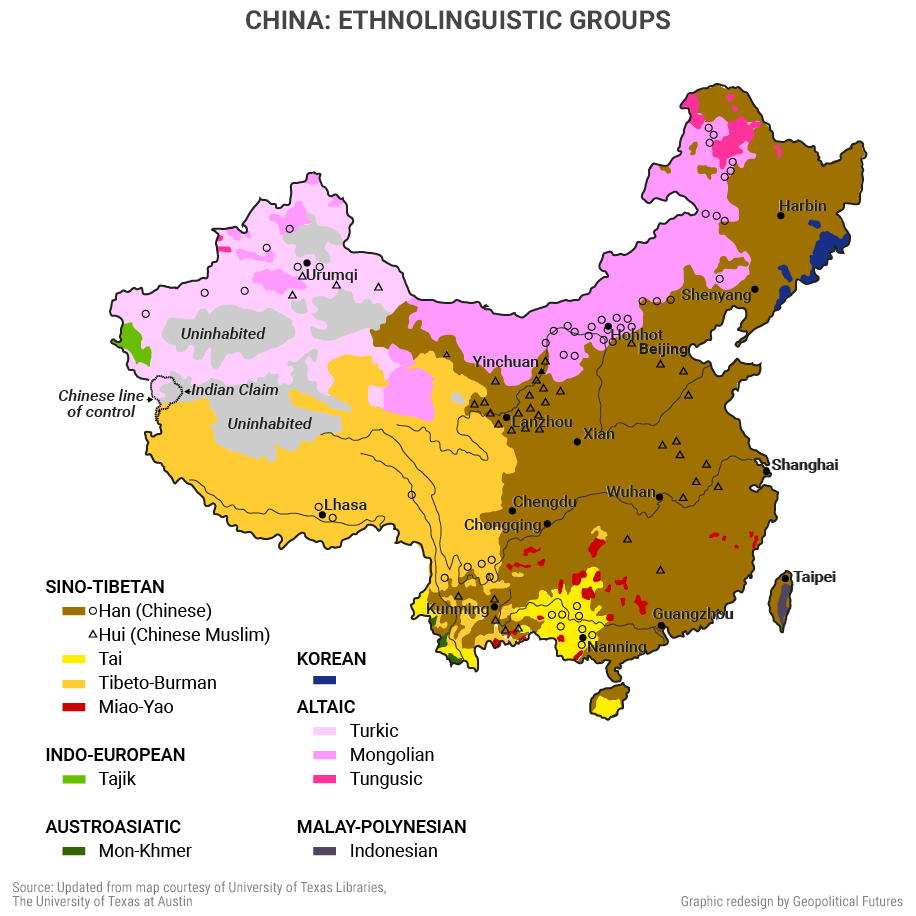

The key phrase in that sentence is “the unity of the Party, the country, and people of all ethnic groups.” When Xi says this unity is critical to the fate of the party and the country, he is not exaggerating. China is as diverse a nation as it is a populous one. While there is undoubtedly a Han Chinese core group, China is made up of multiple ethnic groups, each with their own distinctive language and culture. The People’s Republic of China is remarkable precisely because of the high degree of control it has been able to exert over the entire country. Chinese history is rife with epochs of regionalism and fragmentation.

Unity is of existential importance to the Chinese government. And Xi is issuing a directive to the media to recognize that truth, and to write with that issue in mind. The notion of individual rights and freedom of the press may be very different in the West than in China, but when the matter at stake is national security, even liberal democracies manipulate the news.

The United States, for example, has enforced censorship of the press in the name of national security. This has been true during every major war the U.S. fought in the 20th century – from World War I up to the first Gulf War. The U.S. has also tried to affect the way journalists work. President Barack Obama’s administration has used the 1917 Espionage Act to bring more charges against government employees who share privileged information with the press than all previous U.S. administrations combined. The administration has also targeted U.S. journalists in an effort to force them to reveal their sources. The Washington bureau chief for the Associated Press has been quoted as saying that the Obama administration is particularly secretive and also intimidates both sources and journalists. The potential wide range of Xi’s directives may violate Western sensibilities, but in truth we are speaking in terms of different degrees of control – not diametrically opposed approaches to the media.

The second notable line in Xi’s speech was when he noted, “Truthfulness is the life of journalism, and the facts must be reported based on the truth. While accurately reporting individual facts, journalists must also grasp and reflect the overall situation of an event from a broad view.” On the face of it, this may appear to be an oxymoron. Xi is insisting that a journalist’s life is about the objective truth, and in the very next sentence declares that a “broad view” must inform a journalist’s work as well – in this case the view of the Chinese Communist Party.

However, this is also not a phenomenon unique to the Chinese media. Consider the following recent examples in prominent American media sources. On Jan. 30, the New York Times’ editorial board endorsed Hillary Clinton and John Kasich for the Democratic and Republican presidential nominations, respectively. Writing about Clinton, the Times deemed her to be “the most broadly and deeply qualified candidate” the Democrats have. Kasich, on the other hand, was viewed as an opportunity to “reset the Republican race” – the Times advocating for someone it identified as more moderate than the other potential Republican contenders.

Many respectable newspapers in countries throughout the world make such endorsements, and they make them not always because someone like Xi is telling them to, but because each paper has its own particular ideology. The significance of a widely read paper like the New York Times endorsing potential presidential candidates is not in the endorsement itself, but rather in what the endorsement tells you about the way that newspaper views and understand the world – in Xi’s words, what their “broad view” is.

Take an example from another U.S. news source. Fox News, generally considered to be a conservative media outlet, issued a report on Feb. 16 claiming to show that the Chinese military had deployed advanced surface-to-air missile systems on part of the Paracel Island chain in the South China Sea. Fox’s report set off a series of articles about China’s potential militarization of the South China Sea. Multiple news outlets, including Reuters, carried this provocative quote from U.S. Adm. Harry Harris, head of U.S. Pacific Command: “China is clearly militarizing the South China Sea…you’d have to believe in a flat Earth to think otherwise.” Buried much further down in the article is the more important quote: the U.S. has the military “capability to do what has to be done if it comes to that.”

In this case, the West has developed a particular view about China’s militarization, just as China has its own narrative about its actions in the South China Sea, one which we believe has to do with China attempting to increase national pride at a time of transition and uncertainty in the country. Rather than placing such stories in the context of Chinese intentions and abilities, each headline in the Western media is a breathless gasp that seems to point towards some future military conflict. At the very least, these sources have internalized a world view in which the United States is and should be the world’s predominant military power, free to patrol the world’s oceans and oppose anyone who gets in the way.

Reading open-source intelligence – a fancy term for any news or document that is publicly available – is not only about discovering what is happening in the world. Every newspaper, spokesperson, media outlet and think-tank has its own “broad view” of the world, and that view shapes both what is reported and how it is reported. The first step in evaluating a piece of information is not understanding what happened – that is fairly easy to determine. The more interesting challenge is understanding why a particular source is telling you something and what the presentation of the subject tells you about the issue. The only real difference between China and the West is that China is more transparent about its intentions and biases. For an analyst, that makes them easier to read.