Cyprus, which sits about 50 miles (80 kilometers) off Turkey’s southern Mediterranean coast at its closest point, was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1571 until the empire’s collapse after World War I. Before 1571, Cyprus was held by the Italian city-state of Venice, which exposed the Ottomans to the presence of a foreign power.

At the time, Venice was a wealthy, merchant city-state that, while not particularly powerful on land, had one of the most formidable navies in Europe. The Ottomans did not have to worry about the risk of a land invasion from Venice, but the Venetian stronghold on Cyprus did pose a major threat to Ottoman shipping and trade. The Ottomans needed to maintain open supply lines to northern Africa, which they depended on for much of their trade and therefore wealth, and Venice frequently used its position on Cyprus to disrupt these trade routes. When the Ottomans invaded the island in 1571, the war that resulted between a European coalition (the Holy League) and the Ottomans saw one of the largest naval battles in history and the largest confrontation of galleys (boats powered by oar) in modern history. While naval battles are no longer fought by boats powered by oars, Cyprus’ location still poses strategic risks to Turkey’s position in the Eastern Mediterranean.

This history in part explains the recent friction between Turkey and Italy surrounding energy exploration rights near Cyprus. On Feb. 9, Turkish warships blocked a ship contracted by the Italian energy conglomerate Eni that was heading toward Cyprus to begin exploring for natural gas, marking the first time in recent history that Turkey has actively blocked passage of a European ship.

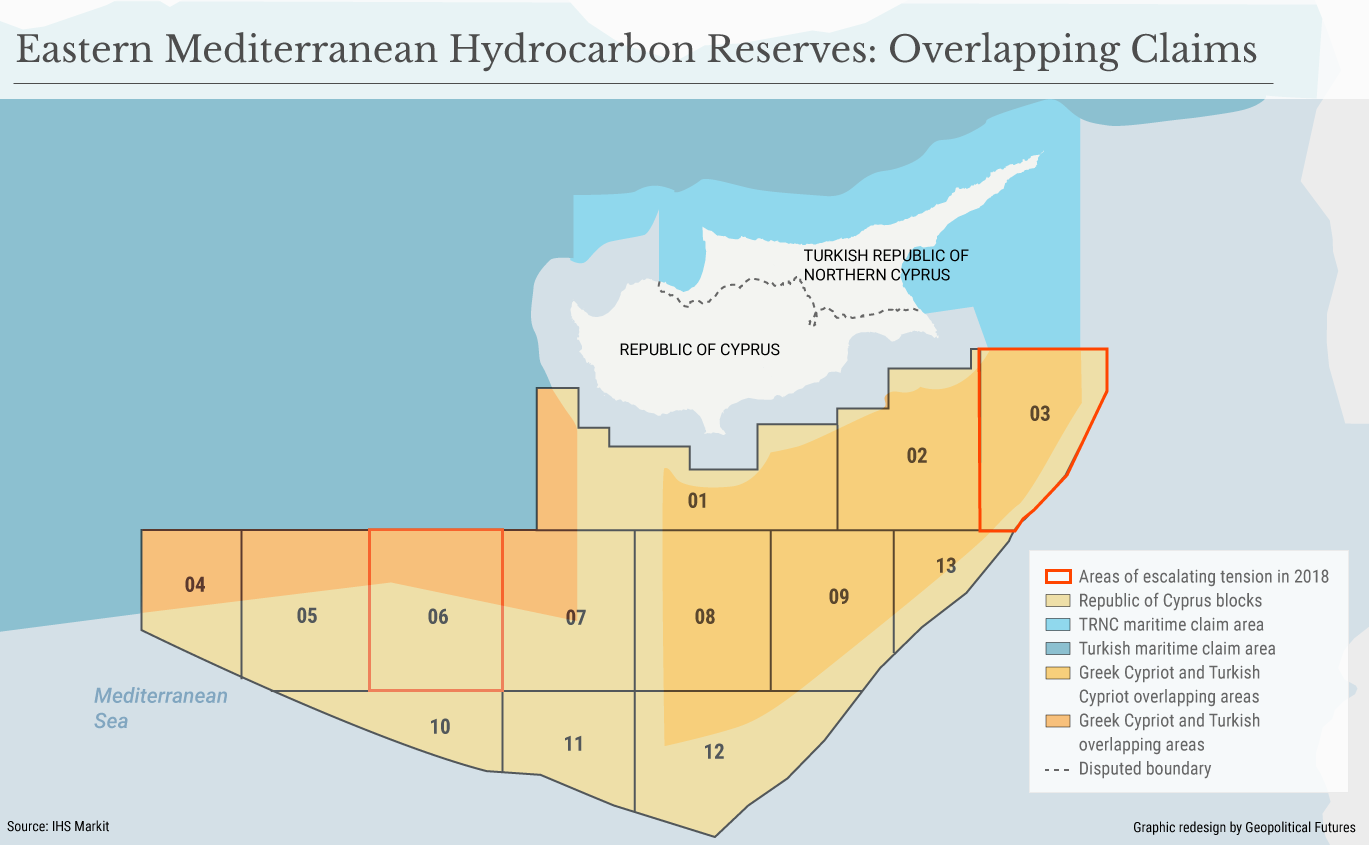

Eni, France’s Total and Exxon Mobil are all licensed by the Greek Cypriot government to engage in natural gas exploration off the southern coast of Cyprus. But Turkey claims that Cyprus had no right to dole out drilling contracts to the European companies since the new reserves, which are in block 3 of Cyprus’ exclusive economic zone, fall under the jurisdiction of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. However, while Turkey claims that Northern Cyprus’ EEZ overlaps with that of the Republic of Cyprus, no other country besides Turkey recognizes Northern Cyprus’ sovereignty.

Turkey’s recent confrontation with Italy, while a far more minor affair than in the past, has significant historical precedent, and the geopolitics underlying this precedent remain today. To establish a greater buffer space to its west, Turkey must have control of the Eastern Mediterranean, and this control hinges upon Cyprus.

To date, Cyprus has been a weak state, and Turkey’s primary concern in the Mediterranean has been its longtime rival Greece. (Antagonism surfaced this week when Greece claimed that a Turkish coast guard ship purposefully rammed a Greek coast guard ship in the Aegean Sea.) If Cyprus were to open its doors to Western Europe to take advantage of its newfound resources, Turkey would then be faced with a situation in which countries far more powerful than Greece have vested economic interests in the island that depend on Turkey’s exclusion.

The current confrontation is unlikely to lead to imminent conflict between Turkey and Western Europe. Instead, Turkey will use the standoff to pry political and economic concessions from Cyprus, where unification talks overseen by the United Nations broke down last year due to Turkey’s refusal to withdraw its 30,000-40,000 troops stationed on the island. Whether this standoff develops into something more than grandstanding depends in part on Turkey and in part on how deeply Italy and Western Europe need to establish and maintain a presence in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East