By George Friedman

China and India have been locked in a military standoff in a remote section of the Himalayas for a couple of months. At first it appeared to be the latest of the minor clashes that have flared between the countries for decades. But this time it has lasted longer than usual. There are two questions to be answered. The first is what is the geopolitical interest, if any, that is driving the standoff? The second is why is it happening now?

The geopolitical issue is that China and India are both heavily populated countries with substantial military forces, including nuclear weapons. They are both industrializing rapidly, and they can both theoretically challenge each other on multiple levels – militarily, politically and economically. In fact, these challenges are all merely theoretical, but geopolitics operates at the level of possibility, and the possibility of a challenge is present, however remote. But before their rivalry can turn into full-fledged war, there’s one massive obstacle that would need to be overcome.

The Moderating Power of Mountains

China and India are next to each other, but in a certain sense they don’t really share a border. The Himalayas separate them almost as much as an ocean would. Getting over the mountains is difficult; roads are sparse and generally in poor condition. It is easier to trade with each other by sea than land. Sending and supplying major military forces into and across the Himalayas is almost impossible. The roads and passes won’t permit the passage of enough supplies to sustain large numbers of troops in intense combat. In that sense, China and India are secure from each other.

Both countries have nuclear weapons, and obviously, anything is possible. But neither side has anything to gain from a nuclear exchange. The Soviets and Americans avoided a nuclear exchange during the Cold War, and the Indians and Chinese have far less to gain from an exchange than they did.

China and India aren’t exactly equals – they’re close economically, but even that is a stretch. But the Himalayas are the equalizer, and the Himalayas aren’t going away.

Conflict by Other Means

Their militaries may not be able to easily cross the Himalayas, but it takes little effort for them to attack each other politically. On the north side of the Himalayas lies Tibet. It is a plateau, consisting of a non-Chinese population, that was temporarily independent until it was reoccupied by China in the 1950s. In the chaos that followed the Chinese invasion, Tibet’s leader, the Dalai Lama, fled to India, where he was welcomed. The Dalai Lama continues to symbolize Tibetan independence, and Tibet continues to be restive under Chinese rule.

What is most important about Tibet is that it lies on the other side of the Himalayas from India. If Tibet became independent by some means and allied with India, then theoretically an Indian force could be based there and, in time, could build up a logistical system that could support an attack into China itself. This is all far-fetched, but given history, a prudent state must take the preposterous into account. History is filled with examples of the inconceivable becoming reality.

This, then, explains China’s obsession with Tibet and its anger at India’s support for the Dalai Lama. The Chinese core, Han China, is protected by buffers: Tibet, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and Manchuria. The last two are not a problem. Xinjiang has a significant Islamist movement. But Tibet is hostile and has a foreign patron. Beijing is therefore, if not obsessed, extremely concerned about Tibet and India.

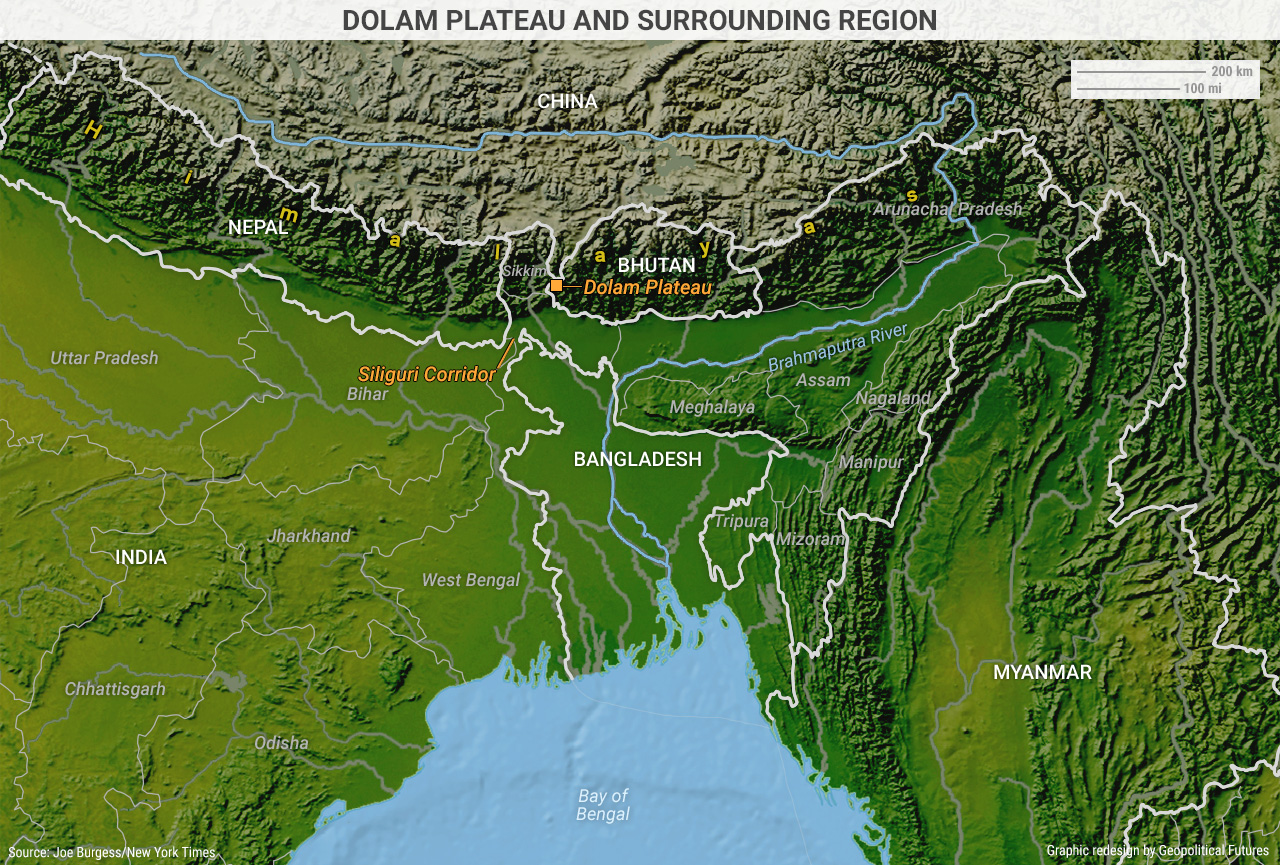

That is the Chinese issue. India’s concern is the same in reverse. There are two other states on the southern side of the Himalayas: Bhutan and Nepal. Both are on plateaus. If China gained control of or a presence in either, it could also mass forces and logistical supplies and potentially threaten India with military force.

Nepal in particular concerns India, because it has been politically unstable and has a Maoist movement. Nepal also values its independence and resents India’s intrusions in its affairs. The Chinese have been solicitous of the independence of both countries, and just this week, China’s vice premier visited Nepal for four days. Before that visit, India’s foreign minister was in Nepal, and Nepal’s prime minister will visit India on Aug. 25. Suspicion abounds. The Indians are as suspicious of China’s intentions south of the Himalayas as China is of India’s north of them.

A Political ‘Solution’

A large-scale invasion would be a logistical nightmare for either country to orchestrate, but technically not impossible. The two did conduct a war in Tibet in 1962 for about a month. Yet the brevity of the war speaks to the high cost and complexity of waging battle at 14,000 feet, so much so that it strongly discourages war. But a political evolution in Tibet or Nepal could change the balance. If Tibet threw out the Chinese and invited the Indians in, China would actually be in danger. If Nepal created a pro-Chinese government and invited in the Chinese while the Indians weren’t looking, the same could happen in reverse. And India is poking at Tibet and China at Nepal, the latter with some possibility of success.

The likelihood of either Tibet or Nepal moving out of China’s or India’s sphere of influence is doubtful. It’s hard to imagine that either could foment a sustainable uprising. If it were to happen, though, it could only be taken advantage of by one or the other having secured a road through the Himalayas that could support the movement of troops and supplies.

It is the Chinese now who are trying half-heartedly to build such a road into Bhutan. But there is a long way to go, and India will resist all the way. If the road even made it through, it would be met with a blocking force. Of course, a pro-Chinese government installed in Nepal or Bhutan would complicate the matter. If the Chinese could rapidly insert some troops, causing the Indians to have to initiate combat against Chinese forces, there is an outside chance that it could work, just as under even more trying circumstances it might work for India in Tibet.

India and China are separated by terrain. There is no military solution to that, but in this case, there might be a political solution. If that were to happen, then we could speak of a China-India rivalry in real terms, rather than in the vague, notional ways we speak now. And both sides are prepared to devote minor military force and major political power to prevent it from happening.

It is unlikely in the extreme that any of this will come to bear. But in a world where the impossible is not an absolute, neither country is prepared to gamble. And so they skirmish in altitudes at the limits of human endurance for a far-fetched possibility. Nations do not take their national security lightly merely because the threat is preposterous.