By Phillip Orchard

Chinese President Xi Jinping made a string of moves over the weekend that reflect the extraordinary power he’s wielding from atop the Chinese system – but also the threats to both his position and his country that are keeping him up at night.

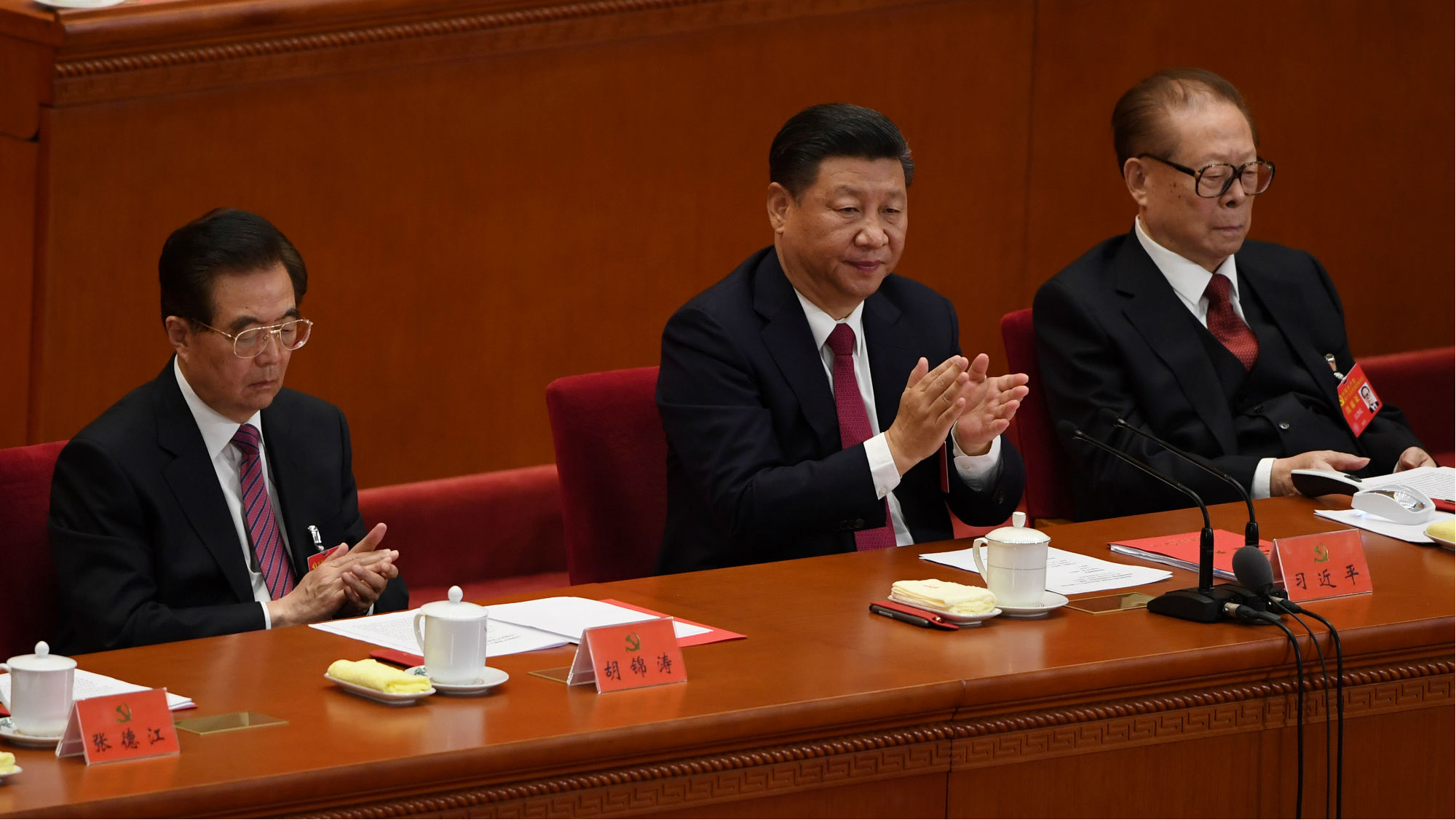

On Feb. 23, the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party proposed that the rule limiting the president and vice president to two terms be removed from the Chinese Constitution at next week’s National People’s Congress. The proposal is certain to be implemented. On the surface, the move confirms what we already knew: Xi has no intention of sticking with recent precedent and stepping down when his second term ends five years from now. This was made abundantly clear at the epochal 19th Party Congress last fall, when “Xi Jinping Thought” was added to the party constitution. There, Xi declined to name a successor to replace him as party secretary in 2021. Xi’s intentions have been further underscored by a string of high-profile anti-graft purges of rising stars (generally from rival factions) seen as potential challengers to Xi.

Xi is motivated by more than mere lust for power. Rather, with China trapped between conflicting political and economic forces as it enters a prolonged period of slowing growth, Xi has launched a wildly ambitious slate of reforms intended to put the economy on solid footing and safeguard party legitimacy amid the coming storms. This reform drive will not be completed by the end of Xi’s second term.

Meanwhile, a growing consensus has emerged among Chinese elites that a strongman is needed to see these painful reforms through and respond decisively to a crisis. The previous model, which emphasized consensus and spreading powers among elite factions, is seen as having left Xi’s immediate predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, too weak to tackle threats to party legitimacy such as unchecked corruption – and prone to paralysis in a crisis.

This doesn’t mean Xi is immune to resistance, though. There will be winners and losers with every reform, and massive amounts of money and power will be at stake. The risks of a destabilizing power struggle will only grow during times of heightened economic duress. Thus, power consolidation is a never-ending endeavor for Xi, however successful he’s been in sidelining rivals and tightening his grip over critical levers of power.

Why the Presidency?

Still, Xi’s decision to spend political capital on the presidency is a bit curious. In nearly all aspects of the Chinese system, positions of party leadership supersede those of the state, including the presidency. It’s largely a symbolic office, with few formal powers. Indeed, under the rule of paramount leader Deng Xiaoping from the 1980s until the early 1990s, the position was always held by a figurehead. It only began to be held concurrently by the Communist Party secretary when Jiang Zemin took power in 1993.

There has been some thought that Xi would eventually step “aside” rather than “down” and try to wield power more from behind the scenes in a manner akin to Deng, who was China’s most powerful leader since Mao, despite never holding the titles of president or party secretary. If Xi were looking for a way to deflect pressure over his apparent disregard for party norms and precedent, one possibility would be to install a figurehead as president five years from now, with Xi continuing to serve as party secretary and chairman of all-powerful bodies such as the Central Military Commission. Xi, of course, could still choose to go this route. But evidently he wants the ability to stick around in the role if necessary.

There are practical reasons for Xi to hold on to the title of president. For one, the president is the official face of China internationally. At a time when China is becoming increasingly active across the globe, there’s political value at home to being the one consistently in the spotlight abroad. Allowing someone else to be the one rubbing shoulders with fellow heads of state could also conceivably threaten Xi’s control over Chinese foreign policy. Second, even though the office of the president matters little today, power in the Chinese system is fluid. It’s not hard to see a scenario in which the office is imbued with powers by rivals attempting to contain or challenge Xi outright. So, Xi is acting now – while he’s strong – to give himself options in a future when socio-economic and political winds are highly likely to be blowing less in his favor.

Containing the Gray Rhinos

The complexity of the economic and political challenges facing Xi during his second term was reflected in two other moves over the weekend. On Feb. 23, Chinese regulators seized control of Anbang Insurance Group, a vast but heavily indebted conglomerate known for its overseas acquisition binges, and charged its chairman, Wu Xiaohui, with economic crimes. (Wu has been detained since June.) And on Feb. 24, State Councilor Yang Jing was sacked – just a month ahead of his scheduled retirement – for colluding with “law-breaking businessmen and society people.” According to the South China Morning Post, Yang is believed to have taken bribes from another disgraced tycoon, former Tomorrow Group chairman Xiao Jianhua. Chinese authorities reportedly snatched the billionaire from a Hong Kong hotel more than a year ago, and he has remained in detention ever since.

Since the beginning of Xi’s first term, his administration has been gradually intensifying pressure on debt-fueled Chinese conglomerates known as “gray rhinos,” with several over-leveraged firms such as HNA, Fosun and Dalian Wanda being forced to sell off newly acquired overseas assets over the past year and scale down their financial services offerings. This crackdown demonstrates just how tightly intertwined Xi’s economic and political concerns are.

Power politics is certainly playing a part in the effort. Yang, for example, was also the top aide to Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, who has been largely sidelined by Xi but remains a potential challenger to the president. Both men hail from one of the two major factions Xi has tried to dismantle via his anti-corruption campaign. Wu, meanwhile, is also believed to be highly politically connected. (He married Deng Xiaoping’s granddaughter.) Allowing such deep-pocketed figures to try to forge independent bases of political power or resist Beijing’s reform agenda would be a direct threat to Xi and to party stability.

Broader economic risks are also at play. Perhaps the foremost policy focus of the Chinese Communist Party this year is eliminating financial risk, which Xi elevated to the level of national security last year. This requires a herculean effort, given the scale of the Chinese economy’s reliance on debt-fueled growth. And it’s forcing Beijing to take on the country’s weak regulatory agencies, state-owned enterprises, the banking sector, sources of capital outflows, provincial and local governments, and more – all at once.

Large financial holding companies like Anbang and Tomorrow Group, among their other problems, are seen as contributing to a boom in shadow financing that, according to regulators, poses a systemic threat to the Chinese economy. Indeed, it’s hard to see how Anbang’s business model, which was raising money for overseas acquisitions by selling extremely high-yield investment products thinly disguised as insurance policies, can be sustainable without implicit guarantees of state backing during a downturn. (Anbang has some 2 trillion yuan, or $316 billion, in assets.) This raised the specter of tens of thousands of ordinary investors taking to the streets after being left empty-handed should any of these firms default. And mass unrest is what Beijing fears most. Meanwhile, the private conglomerates, which have notoriously opaque ownership structures, have also been accused of serving as vehicles for Chinese elites to move ill-gotten wealth offshore, potentially undermining Xi’s anti-graft campaign.

Beijing is moving forcefully to shore up the private conglomerates and clip the wings of their ambitious tycoons while the economy is reasonably stable and Xi is unassailable. But it’s unclear how easily the government will be able to do so without overburdening state banks already trying to shed toxic assets, or without furthering a liquidity crunch that ripples into other parts of the economy, or without bilking everyday Chinese investors who’ve been promised the world. As with most of Xi’s reform agenda, this effort is riddled with unsavory trade-offs. However long Xi decides to stick around, heavy will be the head that wears the Chinese crown.