By Lili Bayer

The world’s exporters are in turmoil. Over the past days, we learned that Chinese exports fell 2.8 percent in August compared to the same time last year, while Japanese exports declined 4.8 percent. German exports plummeted 10 percent year-over-year in July, while the European Union’s overall exports fell 2 percent between January and July compared to a year earlier. But this data does not come as a surprise: the world’s exporters are undergoing a major crisis, as economies that revolve around selling products abroad struggle to find buyers. But there is now reason to believe that the global economy is entering a new phase of export woes. U.S. demand for imports from some major economies is declining, thus threatening to further undermine the stability of already struggling exporters.

We have written extensively about the exporters’ crisis. In January, we ranked the top 10 victims of the crisis. Large exporters like China and major oil producers like Saudi Arabia and Russia topped the list.

The U.S. is not only the world’s largest economy, but also its biggest importer. The U.S. accounted for 14 percent of global imports in 2015. Demand in the U.S. for foreign goods is thus a key engine of economic growth elsewhere. In fact, troubles in the U.S. economy in large part sparked the exporters’ crisis. The crisis started in 2008, as economic problems in the U.S. and Europe led to reduced demand for goods. This slowdown in demand affected countries like China, which in turn bought fewer commodities. China’s slowdown has continued, and exporters of commodities like oil still grapple with low prices and sluggish demand.

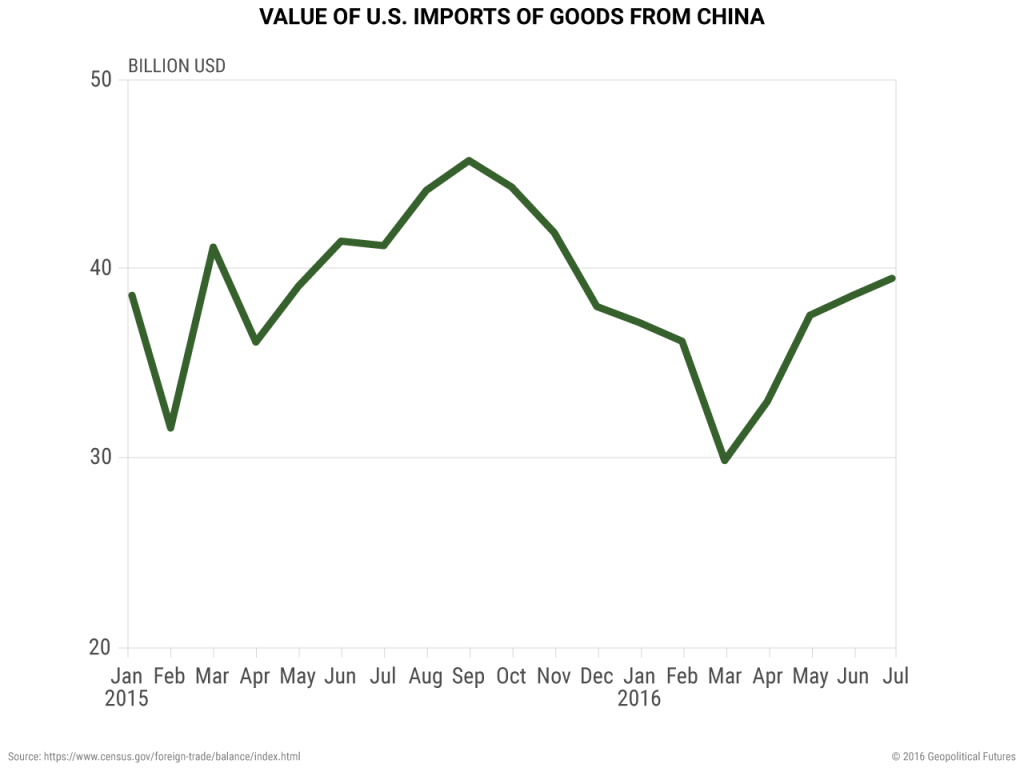

But U.S. demand for imports quickly began to rebound after 2010, and while many European and East Asian economies still struggled, U.S. consumers helped somewhat ease the pain for exporters. Germany, for example, became more reliant than ever on the U.S. market as a destination for its exports. In 2015, the U.S. replaced France as the number one consumer of German exports for the first time. Similarly, the value of China’s exports to several of its major trading partners fell between 2014 and 2015 (Hong Kong by 8 percent, Japan by 9 percent and Germany by 5 percent, according to U.N. Comtrade data). And yet, despite these declines, the U.S. market provided some relief for Chinese exporters, with the value of Chinese exports to the U.S. growing by 3 percent over those two years.

Now, however, there are signals that U.S. demand may no longer be mitigating some of the effects of the exporters’ crisis. U.S. Census Bureau data shows that overall U.S. import of goods each month this year were lower than during the same time in 2015. In fact, the beginnings of a slowdown in U.S. import demand could already be observed following 2014. For example, U.S. import of goods in July 2014 amounted to about $197 billion. In July 2015, that figure was $187 billion and by July of this year it was $182 billion.

The reduced U.S. demand for foreign goods is hitting two major economies in particular that already face serious challenges: Germany and China.

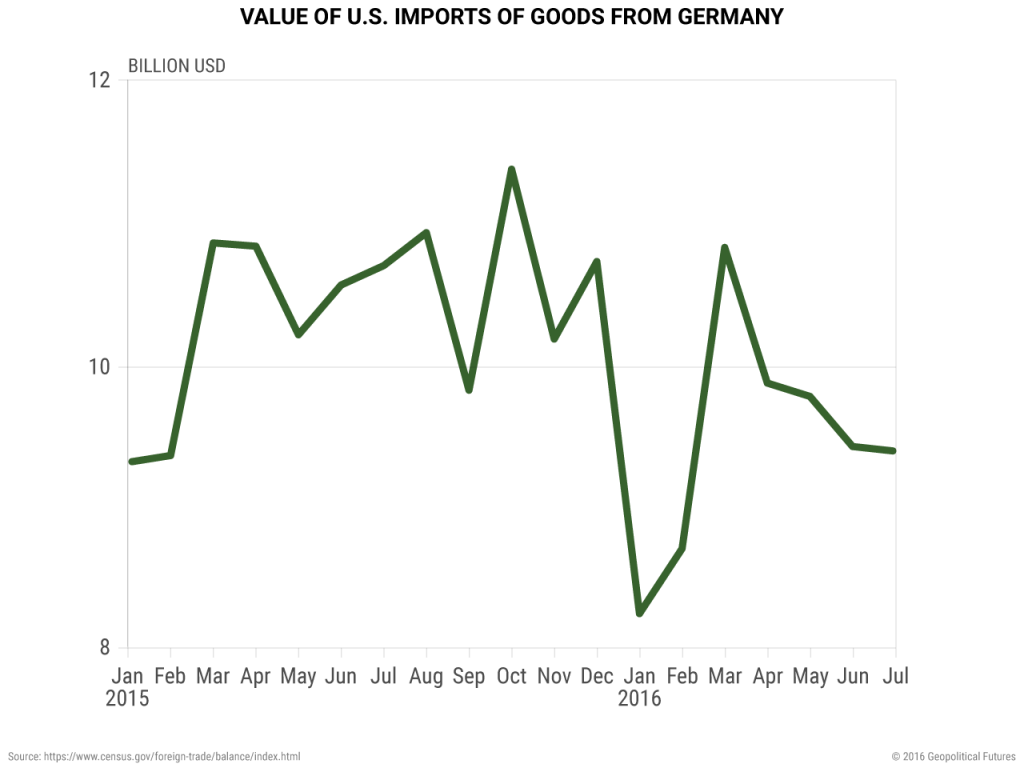

For Germany, the U.S. is a major market. In 2015, 9.5 percent of German exports went to the U.S., according to U.N. Comtrade statistics. These exports consist largely of machinery, cars and pharmaceuticals. The latest data from the U.S. Census Bureau, however, shows that U.S. imports of goods from Germany have declined four months in a row. In July 2016, the most recent data available, import of goods from Germany fell by 12.2 percent. Last week, we noted a German government report that the country’s exports fell 10 percent year-over-year in July. We can now confirm, therefore, that much of that drop was the result of decreased U.S. demand for German goods – a somber development for German businesses that pinned their hopes on U.S. customers in the face of sluggish European economies.

When it comes to China, U.S. imports have also largely declined this year compared to 2015, despite some modest gains in June and July. In July 2016, U.S. imports of goods from China were about 4 percent lower than the same time last year. This fall is not as dramatic as the decline in demand for German goods that month, but 18 percent of China’s exports go to the U.S. What on paper appears like a small shift in reality could have a significant impact on already struggling Chinese businesses.

It is unclear precisely why U.S. demand for imports is declining now, and we will be monitoring U.S. economic indicators carefully for any further shifts in behavior. But it is clear that the U.S. is importing less from countries whose economies are incredibly weak and depend heavily on exports. Perhaps more important, these economies are far from isolated – Germany and China are giants whose economic fortunes define the stability of the world’s economy. It seems like every day we see more cracks in the world’s economic system, and they are growing bigger.