By Xander Snyder

As external pressures continue to bear down on the Chinese economy, the government appears to be losing some ability to manage the situation. Two developments last week restricted the government’s flexibility in its monetary policy. First, ratings agency S&P downgraded China’s sovereign debt from AA- to A+. This followed Moody’s downgrade of China’s sovereign debt in May from Aa3 to A1. This indicates that there is convergence among credit ratings agencies on the belief that China’s credit growth is posing greater risk to its economy. Second, the U.S. Federal Reserve announced a timeline for its plan to sell off assets it accumulated through its quantitative easing program, which was meant to spur economic growth following the financial crisis. Both of these developments will put upward pressure on Chinese interest rates and, therefore, the cost of capital for the central government and Chinese businesses.

Higher Risks

The link between China’s monetary policy and the credit downgrade is fairly direct – a lower rating implies greater risk, which leads investors to require a higher rate of return. Since lending to corporations is considered riskier than lending to the sovereign state, downgrades on sovereign debt ratings will also make borrowing more expensive for corporations.

High-rise buildings under construction are seen near Beijing’s central business district on May 26, 2017. FRED DUFOUR/AFP/Getty Images

The link between China’s monetary policy and the Fed’s move to sell off assets is less direct, but it nevertheless constrains China’s ability to conduct monetary policy at its own pace. China wants to increase interest rates – both to prevent a rapid decline in the value of the yuan and to control the surging real estate market. But it must do so gradually. When the Fed raises rates, however, it forces China’s central bank to raise rates more quickly than it would like to in order to prevent foreign capital from leaving China to take advantage of the higher rate offered in the U.S.

The Fed kept long-term rates relatively static since it began purchasing long-term Treasury securities several years ago, but it will begin selling them in October. This will raise long-term rates on U.S. Treasuries, which will lead to an increase in the value of the dollar and, as investors flock to the U.S. market, could result in a decrease in the value of the yuan. To maintain the strength of its currency, the Chinese government will have to raise rates at a faster clip than U.S. rates.

Main Objectives

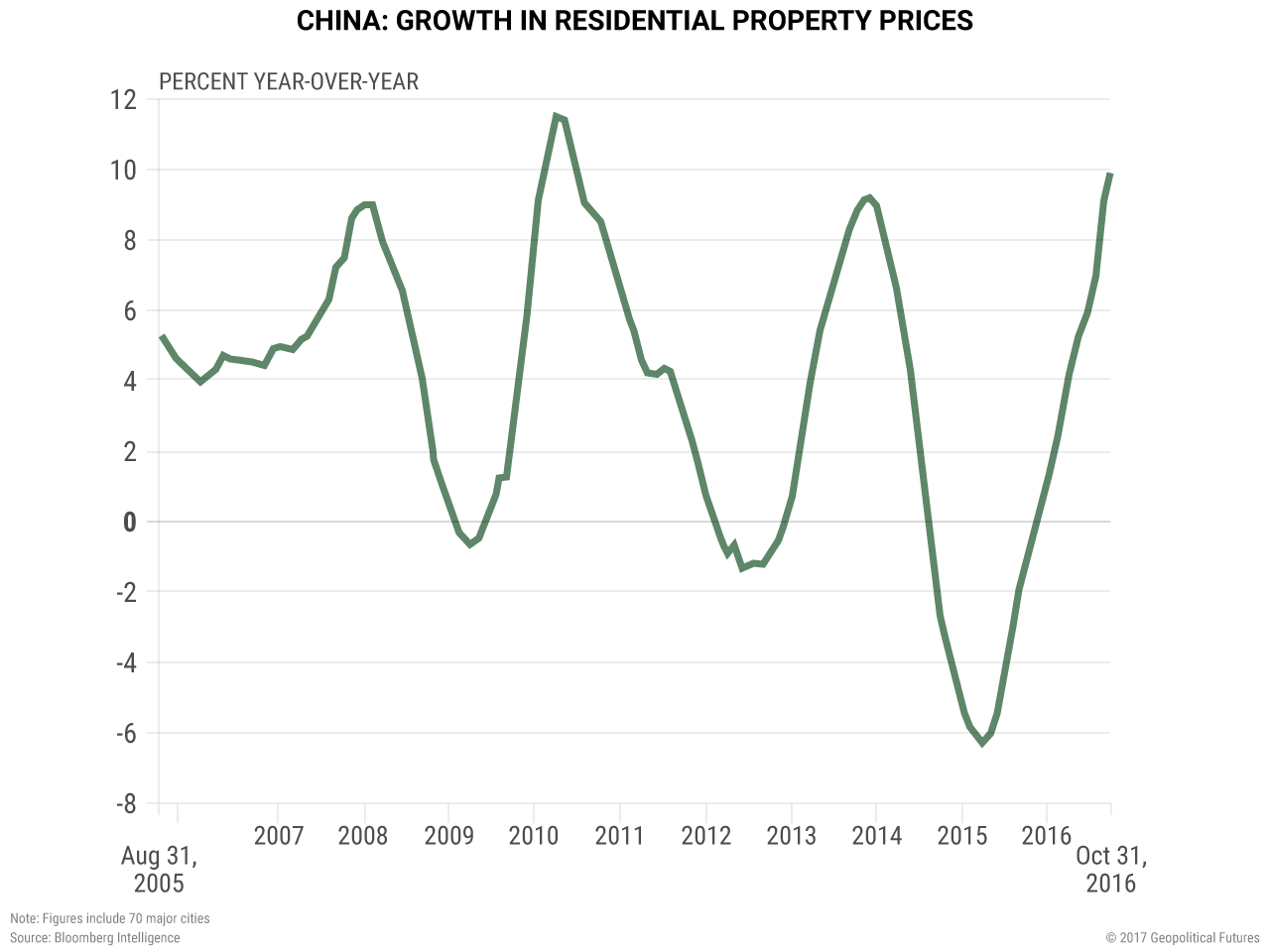

China has been very gradually raising certain interest rates in an attempt to deflate the surge in real estate prices; a collapse in the real estate market could spill over into related industries and China’s broader financial system. The first objective of raising rates, therefore, is to deflate the real estate market without destroying it.

The second objective is to prevent an uncontrolled depreciation in the yuan. While a cheaper currency boosts exports, a collapsing currency creates fear and, potentially, capital flight. China must limit capital outflows to ensure that sufficient funds remain in the country to carry out its infrastructure initiatives and any capital redistribution plans that the communist government hopes will increase the living standards of people in China’s interior provinces.

The dilemma for the Chinese government is that raising rates too quickly threatens its real estate industry. The Fed’s decision, therefore, creates a new dynamic that forces the People’s Bank of China to chase U.S. interest rate rises if it wants to keep the yuan from depreciating too far. No longer does the Chinese government have the latitude to raise rates gradually at its leisure – it will be forced to prioritize either keeping the yuan strong with larger rate increases or preventing a collapse in real estate prices with smaller rate increases.

Though the Chinese government has been effective in the past at managing real estate prices, its maneuverability will be diminished as the Fed sells more assets and increases the rate on long-term Treasury securities. Granted, the Chinese government has many more ways to control its monetary policy than the U.S. government does, and its ownership of land gives it the ability to grow or restrict the land available to developers as necessary. But as the country’s total debt grows – reaching 260 percent of gross domestic product at the end of 2016 – higher interest rates will have a larger effect on the economy. The higher the debt, the higher the interest payments.

The combination of the credit downgrade and the Fed’s decision to begin shrinking its balance sheet adds to the challenges facing the Communist Party as it prepares for its National Congress. As interest rates rise, the government will likely be forced to increase capital outflow restrictions so that it can prevent further capital flight without again increasing rates.

China needs to decrease the level of debt in its economy. But the broader economic risks of rapid deleveraging are still present, and the government’s options are appearing increasingly limited. The fact that policies enacted by the Fed – policies that are entirely domestically oriented – can have such an impact on China’s own economic strategy is a testament to how closely intertwined the two countries’ economies are. Even in a country like China, where the president and the central government have a high degree of power over the economy, political leaders face constraints that are beyond their control.