Christian Smith: Hello and welcome to this podcast from Geopolitical Futures. I’m Christian Smith. In his best selling book, the next 100 years, geopolitical futures chairman and founder George Friedman forecast the rise of Turkey as the major power in the Middle East. With much of the world’s attention currently focused on events in Ukraine, Gaza, Syria and elsewhere. Turkey has remained somewhat under the radar recently, but it has been making moves particularly as a result of significant geopolitical advantages, thanks to a weakened Iran, a distracted Israel and a bogged down Russia. Yet Turkey has also been facing an acute economic crisis in recent years, while its military, although the second largest in NATO, is still far from the complete package. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s rise sees a rival on the other side of the region to challeng potential Turkish dominance. So today on the podcast we take a look at whether Turkey really is on course to become the region’s leading power this century. And to do so, I’m joined not by George, who has locked himself in his study and is refusing to come out until he finishes his new book, but by one of George’s close colleagues, Geopolitical Futures contributor and senior Director of the Eurasian Security, Security and Prosperity portfolio at the New Lines Institute in Washington, Kamaran Bokhari. Kamaran, thanks very much for coming on the podcast. Really good to speak to you. We’re gonna, we’re gonna talk about Turkey, but just to start, I think we are coming. We are recording just as the news is breaking that Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli Prime Minister, has been meeting Donald Trump in the White House for what are seen as crucial talks. And the news is coming out that Donald required force, asked, you name it, Netanyahu to apologize to Qatar on the phone in front of him for violating its airspace when it bombed Hamas leaders in Doha. It’s an extraordinary thing in the world of geopolitics, let alone the world of politics. I mean, what do you make of it?

Kamran Bokhari: Thanks, Chris. Thanks for having me. So look, this is a very significant move. Says a lot of different things, but it’s part of, it’s still a small part of a bigger deal in the making on post war Gaza. So in other words, the deal that the President is trying to look for or trying to reach needs various pieces of the puzzle to be brought together. Now because the Qataris are a key ally and a player in this, they’ve been mediating with Hamas. They obviously had the demand that, look, Israel needs to apologize for violating our sovereignty. Now that obviously is difficult for the Israelis. So I assume there was a lot of back and forth in the lead up to this meeting to which the Prime Minister of Israel basically said, okay, I will do it. And of course there’s a give and take. These things are not sort of like easy to arrive at. I mean, these kind of compromises, if you will. There’s a lot that goes behind the scene, a lot goes on behind the scenes that we don’t know about. And when we do, it’s much later and it’s still the partial sort of truth of what happens. So. But the big thing is that this is part of a wider geopolitical tapestry that has to take shape. And that is has to do with the meeting that the President had on the sidelines of the United Nations General assembly session with leaders of eight Arab Muslim states. Saudi, Turkey, Pakistan, Indonesia, uae, Jordan, Egypt, Qatar. And so that meeting was about what to do in terms of who’s going to be responsible for post war security in Gaza. I had written a GPF article back in May predicting that if Israeli long term occupation of Gaza is unacceptable to the international community, and then the question is then who will be responsible for security? There is no Palestinian state. A vacuum will have emerged with the dismantling of the Hamas regime. The United States is not putting any forces in. There is no other country. And that’s what we’re seeing unfold right now. And so this is huge. I mean, and to sort of connect to our topic, I do want to point out to our listeners that the seating arrangement in that meeting between the President of the United States and those eight Arab Muslim countries was very telling. So you had President Donald Trump at the head table and next to him was the President of Turkey, Rajp Tayyip Erdogan. And everybody else was sitting on the sides, on one side or the other. So that sort of really tells you or it’s an indicator of the role that Turkey is playing behind the scenes. And now it’s worth mentioning that Turkey is a very close ally of Qatar as well. So things seem to be coming together. There’s some indications that the Pakistanis are willing to commit troops, you know, for this task force. The details are not there. Nothing is set in stone. But we’re seeing things come together. And the big thing here is that it also comes at a time when Saudi Arabia did a strategic mutual defense agreement with Pakistan in order to sort of manage not just its own security, but the broader geopolitics and the broader security of the region.

Christian Smith: Well, I mean, Trump, while we’re on the subject, I suppose Trump keeps talking about how we were very close to a peace in Gaza, or we may well be. I mean, do you think that’s likely? Do you think that these are all the chess pieces in motion that are coming together to arrange that? I suppose.

Kamran Bokhari: I mean, we’ve seen the president in the past say things that, you know, the timing didn’t work out or it was slightly premature. But the level of activity that we are seeing on multiple fronts, as I mentioned, the Saudis and the Pakistanis doing a strategic mutual defense agreement, the American president meeting with the heads of eight Arab Muslim governments, Netanyahu going and making this call, and, you know, everything that’s being seen right now suggests that there is considerable progress has been made. I mean, you have to understand that the president needs a win and, and, and, and very soon. Why? Because, you know, the poll numbers are buckling, if you will, under the weight of so many things. Ukraine hasn’t worked out. In fact, we’re, it looks like we’re going in the opposite direction. China is operating at a cadence of its own. There’s nothing rushing there. It’s a separate conversation that the Americans are having with the Chinese. And, you know, you don’t see anything else. Iran is not budging, so he needs a win somewhere. And it seems like this is materializing. I don’t want to get ahead of myself, but it’s looking promising. To what extent and when will all of this come together? It’s really not clear.

Christian Smith: Well, let’s have a look at Turkey. Now, as you suggested, Qatar is a very close ally of Turkey. Recep Tayyip Erdogan was, of course, visiting Trump very recently at this meeting of the leaders of Middle Eastern countries. I mean, to take it back, I suppose, George, forecast in the next 100 years that Turkey would emerge as a great power, the great power perhaps in the Middle east and to an even to an extent in the Balkans as well, in many ways reflecting the former Ottoman Empire, although not actually reforming it in any respect. But in large part that was going to be because the US And Russia would reduce their presence there. I mean, do you think Turkey is on its way to becoming that great power? Is it already that great power?

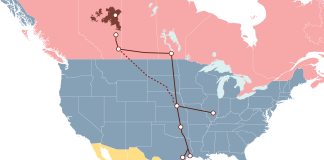

Kamran Bokhari: So these kind of things are difficult to sort of identify. You know, when exactly does a country decline and when does it become a great power? So you can’t sort of capture that moment. So my answer to you would be, I think it’s already on its way. You know, it’s still in early stages. But look, it was bound to happen, because if you think about sort of, just sort of the first, let’s look at the geography. It doesn’t matter who controls what we used to call Asia Minor or the Anatolian Plateau or this land bridge between Asia and Europe that we now call the Republic of Turkey. You can go all the way back to Byzantium and you can see, you know, how Byzantium, the Eastern Roman Empire, was a major power. It was only replaced by the Ottoman Empire. It’s a strategic location with the Black Sea to the north, the Mediterranean to the southwest, the Middle east to the south and southeast. You have the Caucuses to the east and you have Russia to the north and Eastern Europe and the broader European continent to the west. So any, you know, regime or nation that occupies this piece of geopolitical real estate is in an advantageous position to project power. Now that doesn’t, that geography doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll be successful. There were lots of regimes that came by. I mean the, just prior to the Ottomans, you had two different seljuk Turkic sultanates that were very large, but they didn’t have a whole lot of success for a variety of reasons. So we can’t just say geography, but geography forms the basis and then, you know, it’s based on regime. And if you look at modern day Turkey, the Republic of Turkey, for the longest time it was, you know, since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the founding of the Republic of Turkey and post World War II, its joining of NATO, it was part of the Western alliance against the Soviet Union. The Cold War logic dictated you couldn’t go north because that was Soviet territory. And the Turkish Republic that replaced the Ottoman Empire did not want to play in the Middle east because it saw the Middle east as sapping its energies. And the, the nationalist movement led by Mustafa Kamal Ataturk, he and his associates looked at that whole venture into the Middle east as, you know, detrimental to Turkey’s. So they didn’t go into the Middle East. They were satisfied by being a major NATO ally, major member of NATO and the, if you will, strategic environment was locked in place because of the Soviet Union and the Cold War logic. Now you fast forward and you know, you see the Soviet Union implode and then all of a sudden from the implosion of the Soviet Union, you have a fellow Turkic state called Azerbaijan emerge as a sovereign entity. You have fellow Turkic states further east of the Caspian, the five stands or four of them, the fifth, Tajikistan is, is a Persianate country, emerge from that. And you know, that slowly opens up opportunities the coming to power of President Erdogan, who, you know, sees the Middle east in a special way, unlike his predecessors. And then of course the weakening of Europe, you know, the EU sort of floundering and also opens up opportunities. And so you have this situation and then you Fast forward to 2011. The Arab Spring uprisings also provide for an opening for Turkey. But Turkey was blocked for the longest time in the Middle east by Iran, which is partly explains why the Turks were not successful. The other reason was that they were backing Islamist parties who were the opposition to the Arab regimes during the Arab Spring uprising. And they were not successful. The Muslim Brotherhood style organizations in Egypt and Tunisia and elsewhere. And so Turkey was still circumscribed. And now with what has happened since October 7, 2023 after the Hamas attack and Israel’s response to that in Gaza, but more importantly throughout the region, essentially weakened Iran. So you see Turkey pushing into Turkey was blocked by Iran. Turkey pushing in there you go a little bit back, you know, before the invasion of Ukraine circa 2020, and you see the Turks taking advantage of a Russia weakening influence in the South Caucasus, a Russia more focused and in preparing for the conflict in Ukraine. So the turkshawan opportunity supported their fellow Turkic, you know, nation of Azerbaijan in its war against Armenia and basically punched a hole in what was a strategic hole in what was Russian sphere of influence that also sort of put them right between Russia and Iran. So you’re pressuring Iran from the northern flank and now you’re pressuring Iran from Syria. And so these are, you know, what I’m trying to say here is emerging realities. Now. If Russia is weakening and Russia will, you know, we don’t know what the future of Russia will be, what the outcome of the Ukraine war will be, but Russia is not what it used to be. So the Turks are looking at that and saying, okay, yeah, we have a relationship with the Russians on technology, on arms purchases, on energy, etc. Etc. But we will take advantage of this opening that is being presented to us. So you see the similar openings in Europe with the United States retrenching and before that the EU sort of metamorphing into something less coherent because of Brexit. And now with the pressure from Russia in Ukraine and the United States saying to its European allies, well, you do the heavy lifting and we’ll play a secondary role. That’s a major shift in the US Geostrategy for how it manages the globe. That creates all sorts of issues for the Europeans. You know, the Poles are doing Their own thing. The Germans and the French are doing their own thing. They’re trying to work together collectively, but it’s not the same. So that’s another opening. The Poles are actually engaging the Turks. So in what, you know, is the, the, the, that sort of line of the intermarium of states, you know, alongside the Black Sea on the European side. So you have opportunities for Turkey that it’s slowly taking now. You can see it even pushing out further afield into Mediterranean with, you know, deals with, you know, former opponents of Turkey, the warlords in eastern Libya. And they are now part, they’re now working with Turkey. Turkey is, you know, improving its relations with Egypt as part of a joint stealth fighter program that the Turks are leading called the Khan Project. And so you see all of these pieces of the puzzle and you say, okay, you know, this is Turkey expanding its influence in the region. And now with the new regime in Syria, it’s also going to be shaping the Levant. So you have all these pieces up in the air.

Christian Smith: Enjoying the show? Take a moment to follow and rate us on your preferred podcast platform for video versions of the show and much, much more. Subscribe on YouTube. Geopolitical Futures GPF. That’s GeopoliticalFuturesGPF. And as always, you can find expert geopolitical analysis at geopoliticalfutures.com and I mean, in many ways, it’s a bit like Turkey’s geography in the 20th century. In many respects, it was a strategic disadvantage because it was surrounded by either more powerful neighbors or by less coherent neighbors. Now it’s becoming more of an opportunity. I mean, if we just look at obviously what its most powerful neighbor historically has been, Russia. And of course, through the Ottoman period, or much part of it, it was Russia and Turkey and the Ottomans were key adversaries. I mean, Russia’s war in Ukraine is obviously bogging it down. It’s showing its weakness. You mentioned there, the south caucuses. I mean, what opportunity does that give for Turkey? Is it even just a matter of that it’s now the bigger player in the region that people won’t turn to Russia?

Kamran Bokhari: So that’s a great question, Chris, and I would answer it in the following way. I think opportunity is everywhere on a 360 degree angle for Turkey. In fact, I remember writing a piece on this for GPF a few years back. But the question is one of capability, and I think the capability. While Turkey is a major military power, it’s a growing military power. It has its own defense industrial base that it’s expanding, but it hasn’t sort of engaged in kinetic power projection operations for a long time. So that part is still not there. But more importantly, there are constraints, serious constraints on the Turkish economy because of, you know, inflation, because of the, just the state of the, the Turkish economy in the sense that it’s, it needs far more financial bandwidth to be able to do the kind of things that a great power does and it will it, that needs, you know, some time. There were mistakes made in terms of interest rate decisions a few years ago that the, the government is trying now to rectify. And so I think that that is a arrester in Turkey’s path. And so if your financial wherewithal is not there. So for example, you know, if you look at what they’re doing in Syria, they’re tag teaming with Saudi. The Saudis do not have a military, but the Turks do. So the Turks are providing military intelligence support, strategic support to the new government in Syria, trying to, you know, basically stand it up and establish it on a sound footing. And there are many challenges there. But that’s not the only need of Syria. Syria needs a lot of money to invest to rebuild, reconstruction, to get the economy going. That’s not where Turkey can play and that’s where the Saudis have inserted themselves. Mind you, the Saudis, you know, while they’re willing to cooperate with Turkey in Syria because it, you know, it’s, if you will, neither does Turkey have sort of everything that it needs to play in Syria. And certainly the, the Saudis don’t have it. So they need each other. But all things being equal, the, the Saudis do not want the Arab world to be once again dominated by a, you know, an, a disproportionate amount of Turkish influence. They didn’t, they’re happy to see the Iranians weakened. That was a major threat to the Arab world. Iran, through its proxies, had made major ingresses inside, into the Arab world. They’re happy to see that weakened, but they don’t want it to be replaced by Turkey. So they are trying to sort of contain Turkey within Syria. It’s not going, it’s not going to be possible in the long run just because of the variance in Turkish and Saudi capabilities. But for now, because the Turks need the Saudi cash and for their own purposes in order to stabilize Syria, it’s working for the Saudis. So this is just one example of that. The other thing is the economic relationship between Russia and Turkey. Russia, you know, supplies a good chunk of Turkish natural gas as much as 40 to 45% of its needs. And so Turkey needs an alternative for that in order to be able to push northwards. You know, look, when the Ottomans lost territory to the Russians, Tsarist Russia, they were not happy about it, but they couldn’t do anything about it. Likewise, Russia is not going to take kindly to the Turks playing in their sphere. They’re already very, very concerned about what has happened in the South Caucasus, so they want to limit it there, you know, to Azerbaijan and Armenia. They don’t want the Turks playing too much in Georgia, forget about further north in the north caucuses. They are not exactly thrilled at how the Turks are, you know, on one hand have a relationship with Russia but are also supporting the Ukrainians. And so, and there are two reasons why the Turks would be suspicious of, sorry, the, the Russians would be suspicious of the Turks. First, Turkey is, you know, engaged in unilateral assertion. I mean, it’s on a path towards great power status. But then Turkey is also part of the west, part, still part of NATO. So it’s a double thing, a double problem for, from the, from the Russian perspective. So I think that these complicated relations, likewise, I don’t think that the Turk, it’s in the Turkish interest to, you know, rile up the Europeans by, you know, pushing into Europe now. They have created what is called the Balkans peace platform or some such organization. This was just a few months ago. Noticeably absent was Greece. And Greece and Turkey don’t get along. It’s no secret. And the, the Turkish expansion of influence in the Eastern Mediterranean with ties to Egypt, you know, presence in Syria, growing influence in Libya is worrying for, for the Greeks as well. And likewise, the bigger powers of Europe are also not going to like if Turkey sort of asserts itself too much. The sharks are aware of this. They’re not in a rush. But these are all the places that we can expect them to start to play increasingly as their financial bandwidth allows.

Christian Smith: And I want to, I want to come on to the Middle east in particular and Turkey’s relationship with Saudi Arabia in a bit, because that’s just absolutely fascinating. But, but let’s just look. And you mentioned Turkey’s economy there. Just wanted to kind of dive into, I mean, explain to listeners. It’s got serious economic problems. There were issues with interest rates, as you said. How fundamental is this for Turkey? How critical is it? Can it recover, you know, in the near future from this or is its economy going to be a key factor that holds it back going forward?

Kamran Bokhari: So the situation with the economy is kind of tricky. So if it depends on how long you were on a downward spiral, how much damage was done to the economy, that, then that will tell you, all things being equal, no sort of things coming out of left field surprises. And you’re assuming that, you know, it’s going to be on an upward trajectory, which is a very difficult assumption to make. In fact, no one should make that. And I’m definitely sure the Turks are not making that. Then that sort of, you know, will say, okay, how long it will take, it’s difficult to say with precision. But I’m going to be watching Turkey on two different horizons. So one is the next five years. Okay. Their economy seems to be improving, so interest rates, you know, just, sorry, inflation just two years ago, maybe a little longer, was as high as 80%. So they’ve brought that down to, you know, half that or a little less than half that, but it’s still pretty huge. If, if you’re going to be a country that is going to project power, then this is not a problem. You should have, you should, There are other problems. And then there is financing. You know, the, the, the, the issue of having sort of that disposable income. The Saudis do it, have that disposable income because they’re the world’s largest producers of crude oil. They’re the only ones who can actually have, you know, excess capacity. If there’s need for excess production, they can bring it online pretty fast. That gives them a lot of room to play financially. That’s not the case with the Turks. The, the Turks are dependent on outside powers for energy or, you know, external sources. And so I mentioned Russia and you know, there, the, there is oil that comes from, you know, Kazakhstan. Mind you, Turkey’s also a, wants to be a major energy transit state, fairing oil from Kazakhstan and, you know, Azerbaijan, natural gas from Azerbaijan, Iraq and so, but, but these are the, this is still in the making, if you will. The, the, the, the peace treaty between Azerbaijan and Armenia is so crucial for the Turks because they, that’s a choke point. That’s a bottleneck in that sort of connectivity corridor through the South Caucasus and extending beyond the Caspian into Central Asia. So this is something that is not going to turn around fast enough. So I’m looking at the next five years to see, you know, how much improvement is made from, you know, the very bad situation that I just explained from a few years ago. It’s only been a couple of years since they, you know, they switched policy. They brought in a new central bank governor and I believe a new finance minister to sort of lead this effort and, and, and, and towards recovery, economic recovery. So I think that what we’re looking at is at least the next five years and then, you know, we, it’s, it’s all relative. You know, as you know, the Andrew Marshall, you know, the former head of what used to be called the Office of Net Assessment in the, he conceived of this concept of net assessments that you measure military power relative to others. So I would apply that principle to the economic situation as well, that Turkey will rise or not. But then it’s also a function of who else is rising at the same time in the strategic environment or declining. Because if it declines, then there’s relative opportunity. If it is rising, then, you know, there’s, and Turkey is rising and another power is rising. So there isn’t the net effect. So the, the bottom line isn’t necessarily positive or to the positive to the extent that is required for a country that aspires to be a great power. So I think it’s on, on a slow path. This is a slow brew, if I had to put it. So the next five to 10 years are going to be very telling. There’s a lot that needs to, will unfold. We will know what Russia will look like, you know, post Ukraine war. We will know what the Middle east would look like, you know, what is to become of Iran, which is a major historical rival of the Turks for supremacy in the Middle East. We have to see what happens to Eastern Europe and the European Union and so all these things. And of course, you know, the, the Black Sea basin, which is sort of that arena where, you know, Russia and the, the Turks are playing in. And it’s going to be, it’s going to be fun to watch. It’s, it’s, it. I don’t have predictions, but I do have things that I’m going to be watching for regarding the economy because it’s such a tricky thing. I mean, then, you know, state of the global economy, you know, determines everything else. So, you know, it’s, this is all sort of interconnected and so it’s hard to parse out and say, speak in isolation of what’s to become of the Turkish economy.

Christian Smith: What are those signals that you’re going to be watching?

Kamran Bokhari: So I’m, you know, do the Turks, you know, make further progress in reining in inflation? So that’s number one. Number two is, you know, the, the trade figures, you know, Turkish exports versus its imports. I mean, it’s a country that’s dependent on Natural gas and oil. So if you know, the price of oil rises then you know, that’s sort of puts pressure on the, the Turkish exchequer and then you know, you have to see, you know, whether they’re, I mean the Turkey also needs investments in different areas. So we’re in an age of, of tech. So when it comes to military technology, the Turks are making significant progress. But there’s also, we’re in an age of digitization and AI and whatnot. And how the Turks sort of deploy all of this to turbocharge their economy is something that also bears watching. We, you know, the, you know, what kind of relationship would Turkey have with China for example, especially with the Chinese BRI already networked through Central Asia and now with the Trump route in southern Armenia, opening up the south caucuses and linking it to Central Asia that sort of in some ways benefits the Chinese. The Azerbaijanis are already working with the Chinese to benefit from that. The Turks would like to benefit from that as well. So that’s a different dynamic. What happens to the Chinese economy? You know, the Chinese economy is suffering from lots of problems. Some of them are structural that are not going to be easily resolved. And you know, the competition with the United States that’s sort of writ large. I had a piece in Forbes today about how the, the problem of the, the U. S China conundrum, you know, on one hand the United States needs to have an accommodation at, on a geo economic level with China. But the problem is that, and which makes it hard is that the Chinese want to have that relationship but also want to militarily challenge the United States. So that creates a massive problem. And that is probably the balancing those two imperatives is the biggest imperative for Washington right now, globally speaking. And therefore what becomes of that will also affect the Turks because of just sort of the large Chinese footprint, you know, the economic footprint around the world.

Christian Smith: Just very quickly,Kamran, before we come on to the relationship with Saudi, last year Turkey made a deal with the Kurds with whom it has had difficulties for many, many years. Effective in many ways. An internal civil war. I mean, do you think this is now settled? Is this something that Turkey can move on from and the Kurds can move on from?

Kamran Bokhari: I don’t think so. Look, it’s a multi decade insurgency. We haven’t seen the insurgency in recent years. It died down, but separatism is still there. The problem hasn’t been solved politically and it’s connected to Syria because the pkk, the main Turkish Kurdish rebel group is, you know, organically linked to The Syrian Kurds who enjoy self rule have, at least for the better part of the past decade or so and now with the new government, are trying to sustain that autonomy and the, the Kurds over there. So the deal with the Kurds in Turkey will work to the extent that the Kurds of Syria are integrated into this new state in the making, that the Turks are. The effort that the Turks are supporting the government led by President Ahmed Al Shara, who, who is making quite the waves, you know, in recent weeks with his, you know, presence at the United nations and so on and so forth in his, you know, visit to the United States. So that the big problem with that is the integration of the Syrian Kurds. So if that does not happen, that creates problems for the Turks on their home front as well. So I think that it’s, it’s something that will be a sticking point for quite some time. It’s not going to be easily resolved. And that’s another arrestor in the Turkish path when it comes to the Middle East. I mean, projecting power further afield in, you know, further south or east or even west, you know, in the Middle east requires for Syria to be, you know, stitched together in a way where you have found a solution for the Kurds that does not threaten Turkish interests. So I think that that will be something that they’ll be working on and will constrain their ability to project power in the Middle east. Because the first stop is Syria. I mean, the Turks don’t have much influence even in Lebanon. You know, the Saudis, the French, the Iranians have far more influence over there. So you can see how while it’s looking good for Turkey at a macro level, but when you drop altitude and look at sort of the details, there’s a lot of work that needs to be done in Syria. I mean, in Syria, the Turks are trying to reach an understanding with, with the Israelis. The Israelis are stakeholders in, in a future Syria. You see the negotiations between the Netanyahu government and the Shara government government in Damascus over a security agreement where it doesn’t normalize relations, but at least there is an understanding of, okay, where Israeli troops are not, you know, creating buffer zones well beyond the Golan Heights. And, and that’s destabilizing. So it’s not just the Kurds. It’s also the future sort of understanding with Syria that whatever strategic plans that the, the Turks have are not a threat for Israel and Israeli action does not undermine Turkish efforts to stabilize Syria. So there’s a lot of work that needs to be done.

Christian Smith: That’s really interesting. And, and let’s come on to Saudi now. As you say, you know, Turkey was fairly instrumental in the collapse of the Assad regime, but Saudis now also particularly involved in the rebuilding of Syria, particularly through its, through its money. I mean, in many ways, you know, Saudi has the money and Turkey has, has sort of the heft. But in some ways, I mean, we’ve talked about this before coming on our podcast plus, which is for Geopolitical Futures Club members, if you want to go have a look at that and, and see if you want to, to subscribe to that. But we’ve talked about it in the sense that in many ways they would make very good bedfellows. You know, they’re both Sunni Muslim countries that on the other side of, of the Middle east to each other, really. They are both anti Iran and they both have good relationships on the whole with the United States. Do you think a closer relationship between them in the future is possible or do some of their historic disagreements, will that, you know, continue over the coming decades?

Kamran Bokhari: Yeah, I mean, that’s a great question. And yes, the, it’s, it’s hard to get past history. So in the case, I mean, if you think about it, the one problem from a Saudi point of view is that the Turks are Turks, not Arabs. So the ethnic difference, so yes, religiously they’re both Sunni, but even if you sort of drop, you know, into the details of, there is a variance in these Sunni Islams that they both follow. And so there is that complication if we’re going to just talk about religion. But, but the ethnic factor is huge. I mean, look in, in 1744, 45, the first Saudi state was established in open rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. And the Ottomans at the time were losing territory left and right, you know, both to the Russians and the Europeans. And so they, they didn’t have the bandwidth to respond to the Saudi, you know, insurgency, if you will, or insurrection that led to them declaring themselves as independent of the. Part of the reason why that happened is because of geopolitics and geography. The Ottoman Empire, and this is true for its predecessor empires throughout the history of Islam, going all the way back to the Abbasid Empire, is that whichever empire controlled the Arabian peninsula only controlled the west coast and the east coast. And that too, not fully. So Yemen was always its own thing and Oman and sort of was its own thing. It was because this interior of the country was, you know, harsh desert terrain. So you didn’t, and we didn’t have Technology in those days, and empires did not venture so deep into the desert. You set up shop on the coast and that was it. And then you let, you know, local tribes sort it out and clans, and that was sort of the order of things. But as the, you know, Ottoman grip weakened to the point where the governor that they appointed in Egypt, you know, in the, in the, in the 18th century, they were, it was the early 19th century, sorry, in the early 1800s, they had to rely on that governor, Muhammad Ali Basha, an Albanian who set up his own dynasty in Egypt. And he also became sort of his own thing. So nominally he paid fealty to this to the Ottomans, but he was his own man. They had to rely on his forces from Egypt to push back the first Saudi state. So the first Saudi state lasted for about 75 years, from 1744. 45 to 1818. 1818 is when they was, was dismantled. But it wasn’t the Ottoman troops that dismantled it. It was Egyptian troops that dismantled it, operating on behalf of the Ottomans. And of course, the Egyptians saw this in their interest. So they didn’t do it for free or for, you know, for the Ottomans, any favor. They weren’t doing that. But by the time this happened, the Ottoman Empire was in a state of irreversible decline. And you see, and the Egyptian forces also didn’t set up shop and say, okay, we’re going to have a permanent garrison over here to make sure none of these people come back. And all these rebellious forces, meaning the Saudi Wahhabi alliance, the Sauds being the tribal principles and the Wahhabis being sort of the religious partners of the Saudis. And they left. So six years later, in 1824, you have a second Saudi state emerging and much smaller, but it existed until the 8, about 1891. And again, the Ottomans were in no position to intervene. And this time the Egyptians also didn’t intervene in the way they did the first time around. And they let sort of tribal rivalries, you know, they leveraged that. So they had another tribe called the Al Rashid that were rivals, historic rivals to the Ali Saud. And they fought with each other. And you saw that state collapse. So that’s 1891. By 1891, we’re getting really close to the First World War. And you, you see, by 1902, so the, the descendants or the remnants of the second Saudi state fled to Kuwait. And in 1902, the founder of the modern kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the grandfather of mbs, King Abdulaziz, who’s popularly known in the west as Ibn Saud, he launched the campaign to reclaim all the territories from that his forefathers controlled going back to the 18th century. And the Ottomans were in no shape to stop him. The, you know, the Hashemites were in no shape to stop him who controlled the Hejaz region. And so the, so this was sort of a permanent takeover. Now mind you that since the time of the rise of Islam in this seventh century, this level of, if you will, consolidation or integration of the Arabian Peninsula, obviously Kuwait and the other, you know, smaller Arabic Gulf states, Bahrain, UAE and etc, Oman, they were independent principalities under the influence of the British. So they retained their independence and Yemen was its own thing because Yemen was a complication. But the rest of Arabia for the first time came under the control of a single regime since the collapse of the Abbasid empire in the, in the 9th century. So that’s the history of Saudi Arabia in relation to the Turks. The Turks hadn’t had, were defeated in, in, you know, the Turks were still based in the Levant where they were defeated because of the, you know, the Arab revolt at that time which was done by the Hashemites and others in the Levant siding with the French and the British. And that’s where the Ottoman Empire shrunk and became the, the Republic of Turkey. So that history is hard to overcome. Now if you’re Saudi Arabia and the Arab world has, is weak, it does not have its own power, strategic power or heft as you said earlier, then an ascendant Turkey has to be worrying the Saudis. So yes, there are all sorts of reasons to cooperate but it’s always going to, that fear is always going to be there that hey, you know, we don’t want to lose our own sovereignty. And these are perilous times. A lot of things that were unthinkable in recent years have come to pass. I mean nobody thought, you know, the United States would go bomb the Iranian nuclear facilities. Nobody thought that Israel would go and directly strike at Iran, I mean, or for that matter Qatar. So these are perilous times. The United States is retrenching, the world is unanchored and this is really, really bothering the Saudis. This is why the Saudis have brought the Pakistanis into the mix is that hey, you know, obviously we don’t want to fight with the Turks but it sends a message to the Turks that you know, if you are thinking of expanding your wings in our region, well, think again. We have our Pakistanis here. So it’s complicated because the Pakistanis are also close allies of the Turks. So it doesn’t, it makes it even more complicated. But that’s sort of the landscape and I think that’s what we’re going to look at. I mean, we’re going to have Israel, we’re going to have Turkey, we’re going to have Saudi and Saudi is building a coalition. The first test will be whether they can stabilize Gaza or not post war Gaza and then everything else follows from there.

Christian Smith: AndKamran, to finish, I suppose, I mean, as you say, it’s an, it’s an unknown time. Things are changing fast. And so the unthinkable, as you say, is sort of, is sort of very thinkable now. But does that mean we’re more likely to see be a, the unthinkable of a closer Turkey and Saudi, do you think? Or is it more likely to mean that they’re going to be more on their guard and I’m going to be more, they’re going to trust each other perhaps less than they could otherwise?

Kamran Bokhari: I think for the foreseeable future, that’s actually a really good question because it sort of forces me to think, I think for the foreseeable future, Iran isn’t going anywhere. My understanding is that the Iranians are in such a bad shape right now that they have no choice but to reach an accommodation with the United States. That will give them some respite and it’ll give them some time to revive themselves. Then Iran, the nature of the polity is changing. Khamenei is, you know, 86. He won’t be around for long. We’re looking at regime evolution accelerating and a new Type of version 2.0 of the Islamic regime republic emerging in years to come. So Iran is going to be there on one hand, the Saudis don’t like that and the Pakistanis on their side helps with that as well. But it also sort of serves as a counterweight to the Turks. So, so the Saudis can sort of benefit from that. I don’t know to what extent that they can actually play the Iranians off of the Turks. So there’s that, then there’s Israel. Israel is also a major power and Israel and Turkey have to sort out things amongst themselves. Israel is a counterweight from a Saudi point of view, to the Turks. So this is a very complicated situation. I don’t think that we’re looking at easy answers. So there will be intense competition, but there will be cooperation. There will be sort of this quadrangular relationship involving the Saudis, the Israelis, the Iranians and the Turks. So again, you know, a fascinating time, you know, awaits us in the years to come. And it will be, it’ll be interesting to pick it apart.