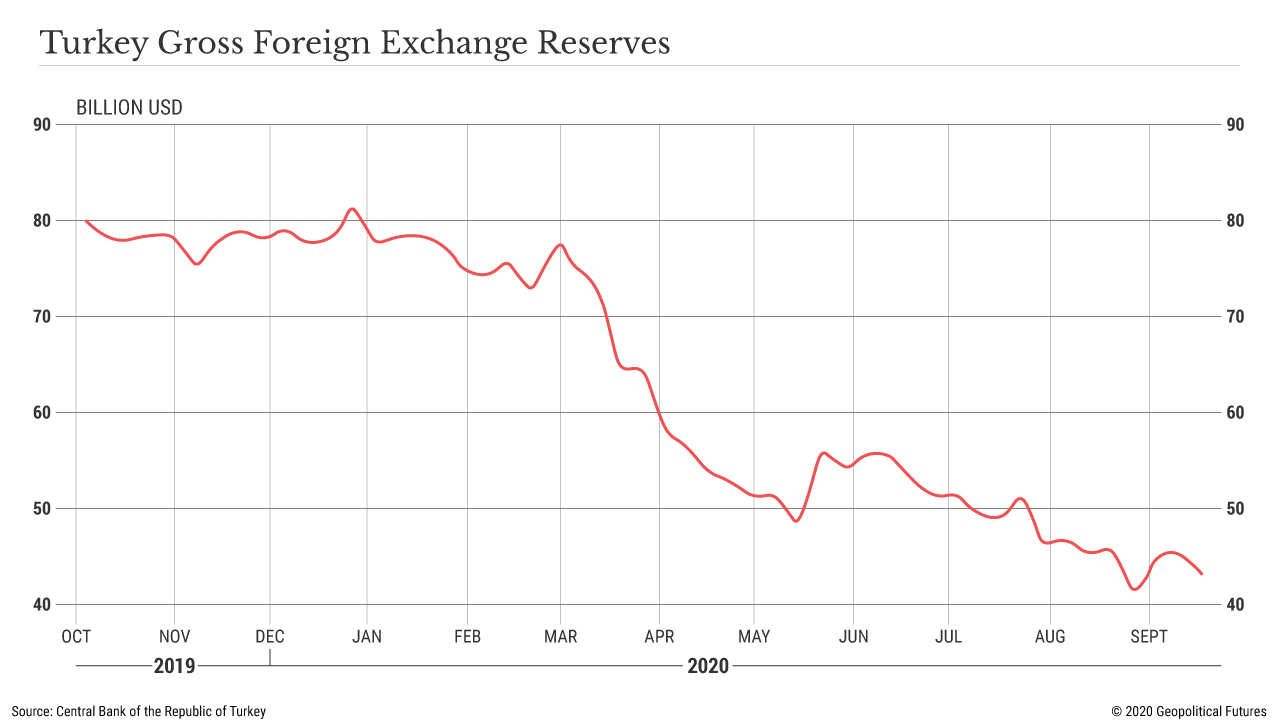

Turkey’s economy is in dire straits. In September, the Turkish lira fell to a 20-year low as investors withdrew billions from Turkey’s currency bond and stock market. In a scramble to keep its currency afloat, the government has blown through almost half the foreign reserves it had at the beginning of the year. With little liquidity left and its largest banks on the brink of collapse, Ankara has realized that its current strategy of fueling economic growth through cheap borrowing cannot hold.

The country has been here before, of course. Just two years ago, it burned through its foreign reserves to protect the lira’s value and hid its debt problem behind defaults and bailouts. But this time is different. Turkey is drawing from far fewer reserves, relying only on Qatari currency swaps to keep them afloat, and its banking sector is depleted. Unless it fundamentally reforms its decrepit institutions – or receives a generous bailout – its economy is in trouble.

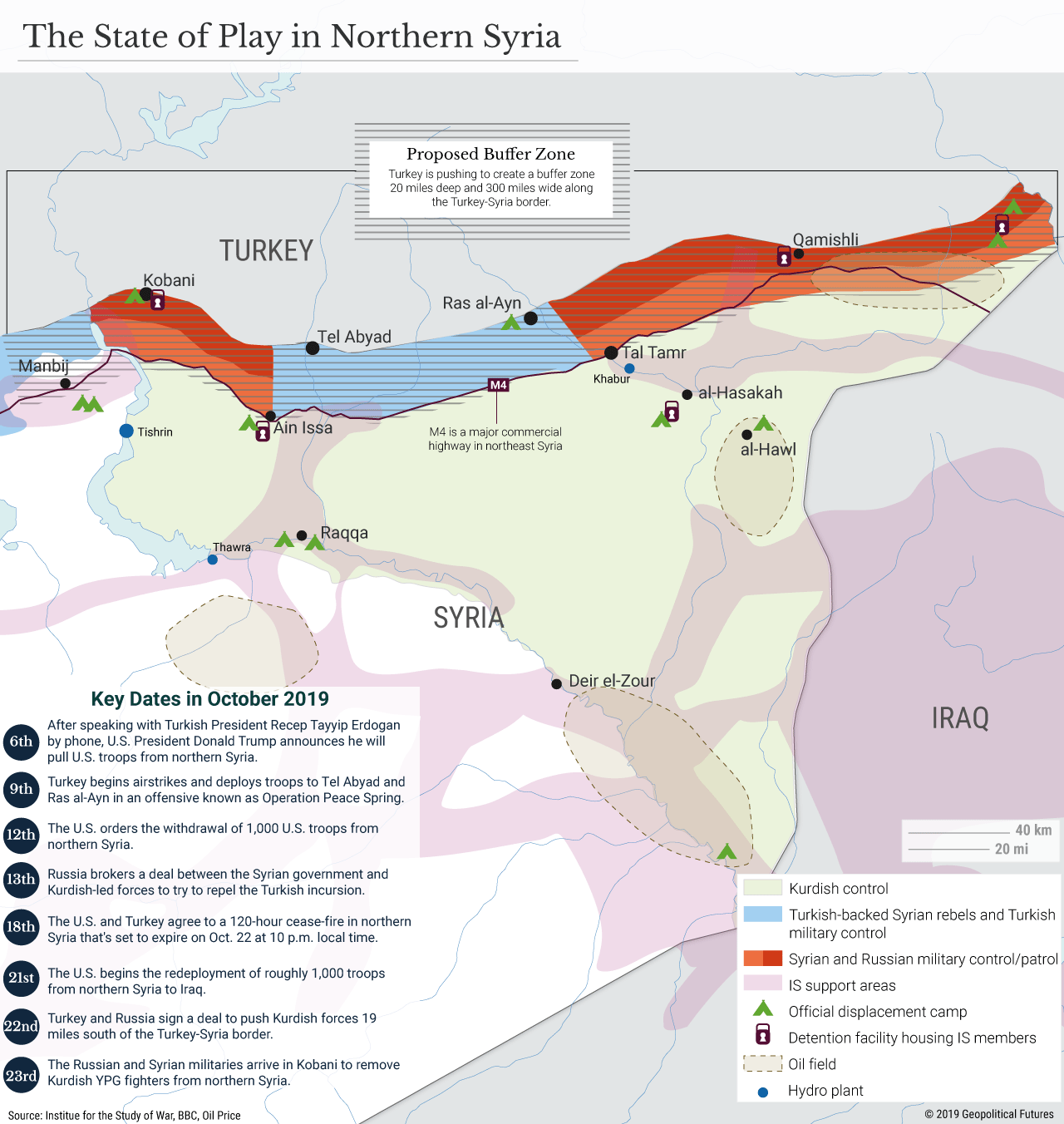

Economic duress can be an agent of change in any country, but in Turkey, with its history of coups and complicated relationship with secularism and Islamism, the ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP, has even more cause for concern because of the potential geopolitical consequences it carries. Turkey has been quickly expanding its regional presence and influencing the behavior of neighboring countries through aggressive action in the Eastern Mediterranean and in northern Syria. But now that the coronavirus pandemic has slammed an economy already in trouble – and with an election just two years away – the ruling party will change its strategy, focusing its foreign policy closer to home and prioritizing regime survival at all costs.

How Did Turkey Get Here?

At the beginning of this year, Ankara had some room to breathe. In December 2019, the economy recorded 0.9 percent gross domestic product growth after a year of recession and debt. GDP growth rates had been fueled by cheap borrowing policies, which created a liquidity crisis and steep bank debt that devalued the lira by 30 percent against the dollar but raised inflation to nearly 12 percent in August. Put simply, the crisis revealed deep structural vulnerabilities in the Turkish economic system.

The problem is that, curiously, Ankara has continued to repeat many of the same mistakes it made before the 2018-19 recession. The government directed Turkey’s central bank to increase cheap loan distribution, which in turn put pressure on the lira and led to increased dollar borrowing from domestic banks to stave off devaluation. As investors began to bet against the lira, the government blew through $65 billion of its foreign reserves from the start of 2020. Eventually, interest rates put pressure on selling and drove the lira to all-time lows (roughly 7.7 lira to the dollar in September), even as the government kept rates below national inflation levels of 11.8 percent. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan prevented the ostensibly independent central bank from changing interest rates for months, concerned as he was that relaxing rates would worsen a future recession. Only in mid-September did Turkey finally adjust its interest rate from 8.25 percent to 10.25 percent, giving the lira a temporary boost to 7.62 against the dollar, but many believed it was too little too late.

Naturally, the timing of Erdogan’s long-term plans will suffer. 2023 was supposed to be a big year for Turkey. It’s the country’s 100th birthday and a big year for general elections in which the ruling party was banking on a comfortable win. More important, it is supposed to be a year of promises kept. In 2013, the AKP rolled out a series of ambitious goals called “2023 Vision” that would be reached within a decade, including an increase in annual exports to $500 billion, slashing the unemployment rate from 11 percent to 5 percent, bumping per capita income to $25,000, boosting the country’s tourism and finance sectors, achieving full participation in state-operated health insurance programs, putting the country’s domestically made automobile, defense and iron and steel industries on the map, and becoming a top-10 economy, with a GDP target of $2.6 trillion. Turkey’s defense industry also set 2023 as its target to roll out eyebrow-raising military technology, promising to domestically produce 75 percent of Turkey’s defense needs, increase defense industry revenues to $26.9 billion, and roll out local drone, naval vessels, armored vehicles, helicopters and main battle tank programs.

It was always a tall order. But not only was it wildly expensive, it lacked attendant economic restructuring and institutional reform that would allow the country to manage high levels of spending. Though Turkey made progress on its automobile production industry, naval production, tourism sector and foreign trade volume, its financial institutions began to crumble.

Despite efforts to create the impression that the country was less in debt than it was, the Turkish government understood that it couldn’t forestall the coming recession. Time was limited, but the government hoped it could stay afloat until elections, distracting the public with a series of foreign policy ventures and a false sense of economic health. The pandemic made this untenable. Just months after it hit Turkey, reports emerged that Erdogan was serious about changing the date of the 2023 presidential election – bumping up the date not by a few days but two and a half years. Doing so would insulate him from the consequences of future bank collapses, economic struggle and inevitable fallout from COVID-19, salvaging the base of public support he currently has to keep a grip on power, or so the thinking goes. Calling snap elections would also prevent newer opposition parties from gaining momentum. While Erdogan has played coy by denying the idea of early elections and stating that “only the opposition” has circulated these rumors, the country’s economic health could force him to reschedule.

Where Will Turkey Go From Here?

Over the past year, Turkey has taken extensive and at times provocative actions to expand its presence along its periphery in the Mediterranean and the Levant, and outward into the greater Mediterranean, Red Sea and Horn of Africa – a pattern that resembles the country’s mighty predecessor, the Ottoman Empire. But to maintain this kind of momentum, Turkey must have a strong economy. If it can weather this financial storm, it can pursue its ambitions of becoming a regional power. If not, then Erdogan will have to fight just to maintain the gains Turkey has made so far.

Until election day – whenever that may be – survival will be priority one for Turkey’s government. Expect the government to double-down on its opposition, increase control over institutions of power, raise taxes, cut services and borrow more money. Ankara will try to scale back some of its most expensive commitments in faraway theaters – such as the Horn of Africa, the Arab Gulf and the Sahel – and reduce foreign military imports, hoping that its own defense industry will see it through. A slowdown on long-term defense projects – particularly conventional projects scheduled to debut in the next 20 years, such as Turkey’s second amphibious assault ship and a line of MILGEM frigates and corvettes – should also be expected.

But don’t think Turkey will stand down in the Mediterranean and the Levant. Turkey will look to politicize opportunities in its periphery to maintain popular support and preserve geo-strategic interests including by increasing the country’s energy independence, preventing violence from spilling over its southern border, defending itself against regional rivals, and so on. Even without the conventional equipment planned to debut in the next few years, Ankara can afford to maintain its strategy of gunboat diplomacy in Aegean littoral waters, using fishing, drilling and small naval vessels to keep up the pressure on Greece and Cyprus.

This strategy is, notably, politically popular at home. A majority of Turks want to renegotiate terms with Greece to expand Turkish maritime territory and thus to stake more claims to hydrocarbon resources in the region. They see Turkey’s harassment tactics as a means to those ends. Even the ruling party’s staunchest opponents in the Republican People’s Party support Turkey’s Mediterranean campaign. Likewise, Turkey will continue its operations in northern Syria and Iraq: It’s simply too important an issue to Turkish voters, who see it as the preservation of their borders against migrants and militant organizations.

But none of this will necessarily lessen the pain of Turkey’s economic disrepair. Laborers at nuclear plants and construction sites are working without wages, with some initiating legal proceedings and protesting poor management. Many small-business owners have had trouble accessing state-subsidized loans, and workers are unable to obtain financial support, leading to higher poverty rates and food insecurity – largely among the AKP’s conservative, lower-class base. These economic conditions will force Turkey to provide some kind of economic relief and impact the future of the ruling party.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East