By Allison Fedirka

As Islamist militant groups attempt to expand their operations into new areas, some have looked to the Sahel region in western and central Africa and seen opportunity. French and U.S. military efforts in this region are often overlooked, but for years they have been trying to stem the spread of extremist organizations. The need for these efforts was made even more apparent earlier this month, when four U.S. soldiers were killed in southwestern Niger in an attack the Pentagon confirmed this week was carried out by Islamic State fighters. French and U.S. operations will be increasingly important as IS and others lose ground in places like Syria and look to expand into new territory.

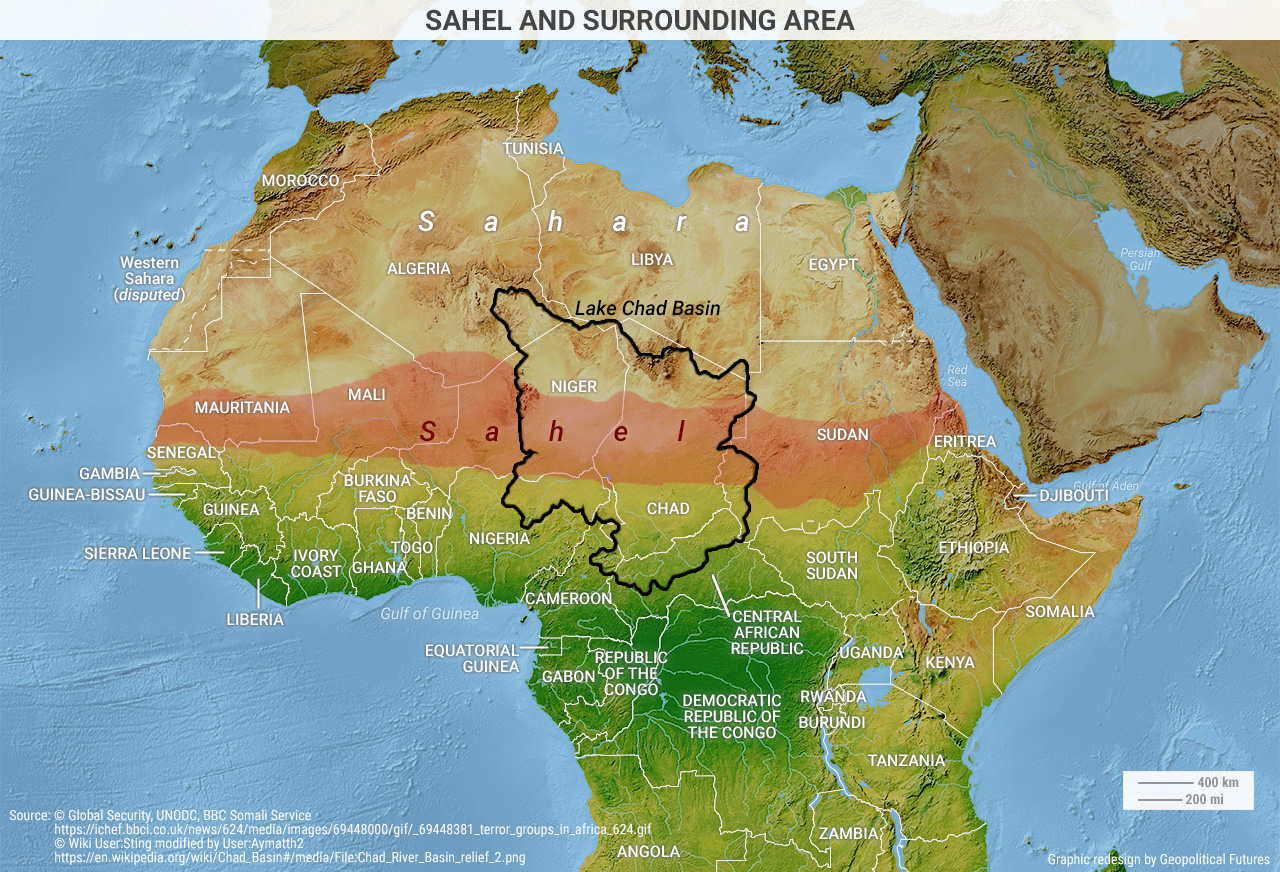

The militant groups exist in pockets throughout the western Sahel and Lake Chad basin. Some, like Boko Haram, which has holdings in northern Nigeria and parts of Niger, Chad and Cameroon, are expansive and relatively well-defined. Others, like the numerous groups in Mali, are smaller and more scattered. The Sahara separates these local groups in and near the Sahel from territory dominated by al-Qaida and IS in North Africa – particularly Libya and Algeria. The main security concern is the formation of a corridor between North Africa and the Sahel that would allow revenue, fighters and operations to merge and flow easily. So long as these groups remain physically and operationally separate, they will stay localized, and collaboration between them will be difficult.

This part of the Sahel can provide revenue sources for groups able to access and control key territory. Trade in illicit activities passes through the region, as traffickers try to get their goods into Europe. Drugs from South America, for example, are transported through Africa before reaching their destinations in Europe. Countries along the northern coast of the Gulf of Guinea and West Africa’s northern Atlantic coast serve as major points of entry. Drugs then flow through Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Burkina Faso and into the Sahara Desert toward Europe. Jihadist operatives have penetrated this supply line by serving as traffickers, and in doing so, they earn a cut of the profits. The region also holds valuable deposits of uranium, gold and other metals that can be sold on the black market.

Recruits undergo training at the headquarters of the Depot of the Nigerian Army in Zaria, Kaduna state, in north-central Nigeria, on Oct. 5, 2017. The Nigerian army trains recruits to tackle the terror threat of the Islamist group Boko Haram in northeast Nigeria. PIUS UTOMI EKPEI/AFP/Getty Images

Jihadist groups like al-Qaida and IS also see this part of the Sahel as a fertile recruitment ground. Islamist and other militant groups in the region are set up locally, and they often have fluid identities, making splits, mergers, shifting alliances and partnerships commonplace. Many of these extremist groups swore allegiance to al-Qaida and IS as the latter gained global recognition. The groups hoped to raise their profile and gain more legitimacy and perhaps resources with this pledge. Two of the better-known groups are Nigeria’s Boko Haram, a faction of which pledged allegiance to the Islamic State, and Mali’s Nusrat al-Islam, which pledged allegiance to al-Qaida.

The two main countries carrying out counterterrorism operations in the region are France and the U.S., which have adopted a containment strategy for their operations. France’s main focus is Mali and other parts of the western Sahel, while U.S. operations have concentrated on the Lake Chad basin to the east. In practice, there is much overlap and cooperation between the two countries. Their broad strategic objective is to prevent the emergence of a transnational threat and the formation of lucrative, illicit trade routes and recruitment centers for jihadist operations elsewhere. But they don’t expect to completely eliminate jihadist groups in the region for two reasons. First, both countries’ resources are already overextended. The U.S. military is active in other regions, and France has used some of its military resources to help reinforce domestic security as it faces a growing threat from terrorism at home. Second, they can achieve their security goals by physically disrupting transit lines and targeting select pockets of militants when necessary.

Because of the region’s challenging geography, the U.S. and France are forced to pursue this strategy at the tactical level by relying heavily on drones, local forces and special operations forces, particularly in the case of the U.S. The western Sahel and the Lake Chad basin are expansive, sparsely populated areas. Their sheer size makes patrolling and monitoring impossible without the use of drones. Planning logistics, including emergency evacuations, is also difficult, limiting the reach and effectiveness of troops. The U.S. uses special operations forces and small strike groups because they are the best suited for “advise and assist” roles. Training of local troops, which contribute much-needed manpower, is also paramount to these efforts.

But the threat to France, and Europe in general, from jihadist expansion in West Africa is higher than it is for the U.S. This is why Paris has been highly committed to its military operations in Africa. North African migrants and travelers can reach the shores of southern France simply by crossing the Mediterranean. Some citizens from former French colonies in Africa have dual citizenship, which makes travel for them that much easier. France has also been the target of multiple terrorist attacks in recent years. Washington, on the other hand, considers the region a low-intensity conflict zone because militant activity there does not directly threaten primary U.S. security interests. The U.S. is much more focused on protecting oil supplies, containing Russia and the North Korean threat.

Islamist militant groups in the Sahel have the potential to contribute to or strengthen other jihadist groups. For this reason, organizations active in the area can’t be ignored and left to their own devices. The current containment strategy at times obscures the role of Western security operations in addressing the threat, but in fact, countries like the U.S. and France don’t need to fix the underlying problems facing West African nations in order to achieve their security objectives there. Instead, they can maintain a lighter footprint and engage in limited military interventions to keep the groups at bay.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East