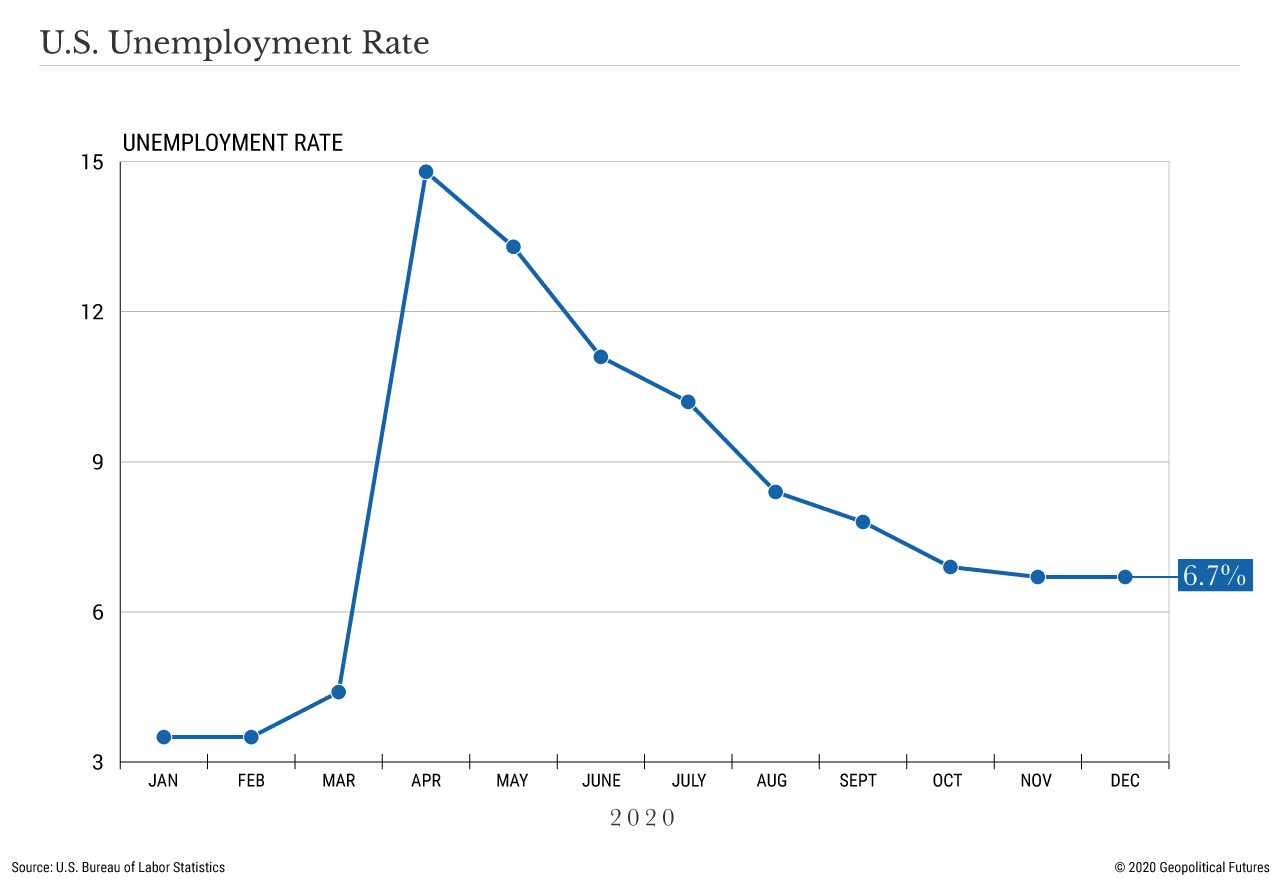

Some 140,000 Americans lost their jobs last month, the largest decline in employment since last April. Yet, the unemployment rate stayed at roughly 6.7 percent. The job losses were attributed to restaurants, travel, entertainment, governments and schools, according to the Wall Street Journal. That explains who cut the jobs but not why the unemployment rate remained unchanged. One answer is the jobs cut were already factored in, say, if employees were let go in previous months. Another is that workers found new jobs, difficult as that may be. The third possibility is that those who lost their jobs dropped out of the workforce, accepting the unlikelihood of finding something new.

The cuts are unsurprising, given the intensifying lockdown measures originally imposed last year. The first casualties are always the places that cannot be enjoyed while wearing a mask. Topping the list are bars and restaurants, whose employees often lack the resources salaried workers have and are less likely to find a similar job in their field. In schools, many cuts likely targeted the custodial and lunchroom staff, who are less urgently needed as many schools are closed anyway.

Job losses give us a sense of what will happen once the pandemic is brought under control. I have written before that I regard a recession as a financial event that leaves most of the economic infrastructure intact. A depression is an event in which that infrastructure is destroyed. Unable to sell to a public without money and unable to pay their lenders, many businesses find their only option is bankruptcy. They close their doors and walk away, never to reopen. In a true depression, business failures become bank failures as banks fail to recoup their loans. That, in turn, makes capital harder to come by. A central bank can always print money and recapitalize the banks, but insufficient demand (that is, money) makes it irrational for a business to assume debt. Getting out of a depression is hard.

My view last spring was that we had until late fall to deal with COVID-19 and restart the economy without risking depression. We are therefore now in a period of risk. The idea that we are at risk of a depression right now may seem preposterous. The banking system appears to be robust, the rate of bankruptcies is not surging excessively, and unemployment is relatively low, so demand is intact. There are problems in certain sectors, of course, but industries such as airlines appear to have weathered the crisis, and brick and mortar retail trade has demonstrated that there can be life after bankruptcy.

It is reasonable to assume that we have economically routinized the pandemic and that we have room to maneuver until we are vaccinated (or choose not to be). But the 140,000 jobs lost in December were decisions businesses made about what they expect to happen in 2021. Leaving aside schools and government agencies (and restaurants and bars, which have been the long-running victims of social distancing), there are certainly other businesses, and more than a minority, making job cuts. The travel industry has already been cut to the bone, and other businesses can let some but not most employees go if they are to continue functioning.

Those 140,000 cuts were made largely by businesses that have a profound understanding of the business they are in and of the appetite of their customers for what they sell. Most businesses have always controlled the number of people they employ – that is, not maintaining a mass of disposable staff. So when they cut jobs, they cut deep, and if they are cutting to the bone they are seeing something unpleasant coming. The cuts will not show up in unemployment figures, nor in banking numbers, nor most certainly in the stock markets.

I think these businesses are seeing two uncertainties. The first is that the efforts of the government to defer an economic crisis have succeeded, but that deferral is not the same as prevention. Deferment makes it likely that as the pressures build, a crisis is coming sooner rather than later. Failures in various economic sectors can emerge suddenly, and those deferrals can sweep into other sectors. When facing a troubling future, the rational move of any business is to cut expenses. And since most viable businesses already control costs vigorously, the only defensive move possible is to cut jobs. Cutting staff just before the new year is an indicator that those who know the economy at its detailed best are very worried.

The second uncertainty is the vaccination program. To be sure, vaccinating 330 million people in the United States is a daunting task, but the fact that we do not know when we will return to normal life, with all its predictability, creates a level of uncertainty that requires defensive action. Being concerned about when this will be over is gauche to some, but time is the essence of business, and at this point the only timeline for a return to normal I have seen is from Dr. Anthony Fauci, who predicted the latter half of 2021. For all we know, it could be longer.

I am not saying that anyone has failed. We have never been in this situation, so it’s understandable that the end game is unclear. But the businesses that have recently had to cut jobs must make decisions on unclear data. They can’t wait patiently for revelation. They don’t know when the government will lose the ability or desire to defer the crisis, nor do they know when the current crisis will end. So it seems to me that a lot of businesses, looking into a forest – dark, uncertain and with little light to reveal anything – have chosen to move into a crouch, in order to survive the uncertainty. At this point, it is not the virus that scares them; it is the fact that there is no way to grasp the amount of time it will take to get past it. And that is the major pressure weighing on the economy.

The surge in job losses can be interpreted in many ways, and the concerns I have expressed may not come to pass. Nevertheless, they can’t be ignored, nor can it be reasonably assumed that the measures being taken to fight COVID-19 won’t have an even longer tail. Economic pressures can continue to mount without showing themselves. My argument is that the pressure is mounting but being contained. That may not be much comfort, since mounting pressures can explode unexpectedly.

Special Collection – The Middle East

Special Collection – The Middle East